Vito Corleone, Alonzo Blauvelt & Smallpox in Italian Harlem

The year was 1901 when the steel barque Moshulu sailed into New York Harbor carrying many Sicilian immigrants for inspection at Ellis Island.

The year was 1901 when the steel barque Moshulu sailed into New York Harbor carrying many Sicilian immigrants for inspection at Ellis Island.

This is the gripping fictional opening scene of The Godfather II, although considerable artistic license was taken by its producer and director Francis Ford Coppola.

The “windjammer” was built in 1904 by William Hamilton & Company on the River Clyde on behalf of a German company. Named Kurt, it was used for bulk transport (coal or grain), not the transfer of migrants.

During World War I, the ship was seized by the U.S. Navy and renamed. It is now a floating restaurant docked in Penn’s Landing, Philadelphia.

In Ellis Island’s Great Hall a nine-year-old boy named Vito Andolini, alone and lost, is hustled through a chaotic mass of new arrivals. In front of an impatient attendant and against the noisy background of many different languages, he does not speak at all.

The youngster is assigned the surname Corleone, the town he had fled to escape his family’s Mafia enemies.

Suspected of carrying smallpox, Vito is quarantined for three months on the island. Kept in isolation, he can only look out from his window to see the distant contours of New York City across the water.

The future Godfather had arrived in America, not realizing that at the time of his confinement fellow Sicilian and Italian immigrants were treated harshly by local authorities as they were held responsible for a smallpox epidemic in the metropolis.

Speckled Monster

Early researchers agreed that this “modern disease” (unknown to the Ancients) had been brought in the eleventh century from Northern Africa into Europe by Islamic invaders or returning crusaders.

Identified as an “import,” smallpox was carried on by European explorers into non-immune indigenous populations, particularly in the Americas.

Identified as an “import,” smallpox was carried on by European explorers into non-immune indigenous populations, particularly in the Americas.

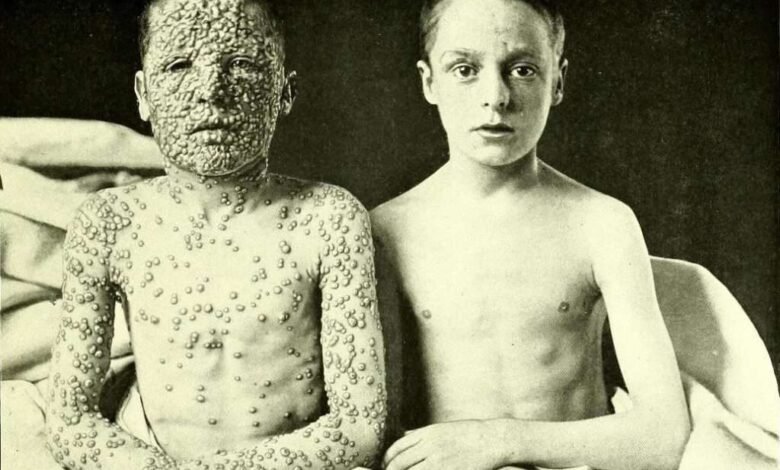

Once infected, a patient began showing flu-like symptoms. By day four, pustules or “pocks” appeared in the mouth, throat and nasal passages. Within twenty-four hours, a skin rash surfaced.

For some, this rash turned inward, hemorrhaging beneath the skin and through the mucous membranes. These patients died quickly.

For most, the pustules pushed to the surface; scabs started to form late in the second week. By week three, fever subsided and scars replaced scabs. Survivors were now immune, but pockmarks remained. The course of the disease took about a month.

The “speckled monster” of smallpox was regarded with terror. About three out of ten patients died a harrowing death. There was no cure.

The disease was castigated for being “doubly cruel.” It did not just herald imminent death, but disfigured victims by “pitted” scars which often led to complications.

Scottish poet Thomas Blacklock was left blind as a result of corneal scarring after ulceration (a leading cause of blindness).

Potter Josiah Wedgwood contracted smallpox as a child in 1742. He survived, but suffered a secondary infection in his right knee which would lead to an amputation.

Retrospectively gathered clinical evidence suggests that smallpox left some male survivors impotent.

Other than the plague, smallpox was responsible for more deaths than any other health calamity. For those who watched the gruesome symptoms from close by, the disease seemed to confound the powers of description.

Whereas the plague gave rise to a wealth of artistic representations, smallpox has no such history. Artists were reluctant or unable to deal with the theme. Very few painters dared to portray a patient – with one notable exception.

Antwerp-born Justus Sustermans was court painter to the Grand Dukes of Tuscany in Florence. The family was struck by a smallpox outbreak in the region in the autumn of 1626 with five members falling ill.

In October 1626, the artist painted two portraits of Ferdinand II de’ Medici, aged sixteen, at two stages of the disease (days seven and nine). Although Ferdinand recovered, the patient’s grotesque and repulsive painted images were received with shock and horror.

Job’s Boils

Smallpox came to America with the arrival of the first Europeans. It devastated generations of Native Americans (and helped assure the Spanish conquest of the Aztec and Inca Empires), created disastrous loss of life amongst enslaved Black people and was an existential threat to the colonies.

There were two means of combating the disease: quarantine and inoculation. When employed efficiently, isolation helped to stop it from spreading out of control. In the colonial period, the method was used by colonists and Native Americans alike.

Inoculation was introduced to the West in the early 1700s at London’s Royal Society, the leading scientific institution of the era. It caused fierce debate.

Based on Enlightenment principles of inquiry and observation, Voltaire (who learned about the process when living in London between 1726 and 1728) and like-minded thinkers championed inoculation as a triumph of empirical research over superstition and cheered its potential of improving public health.

In the summer and fall of 1721, smallpox ravaged Boston. The epidemic began when the British naval vessel HMS Seahorse arrived on April 22 with infected crew members on board. Although they were quarantined, the virus spread quickly, prompting residents to flee the city.

Boston had experienced outbreaks before. Just prior to 1721 a quarantine hospital had been constructed, but in spite of preventative measures over eight hundred residents died during the epidemic.

Having survived smallpox himself, Rev. Cotton Mather rejected the Church’s opposition to inoculation, arguing that medical science was God’s gift to mankind.

He encouraged Boston’s physicians to take up inoculation. They declined. Only surgeon Zabdiel Boylston inoculated his son and two members of an enslaved Black family in his household. These were the first three recorded cases in America.

The public’s response was hostile. Unease about inoculation lingered as opponents denied its safety and efficacy. The technique itself was unpleasant.

It involved the deliberate infection of an individual with the virus (“controlled exposure”), usually through an incision in the hand.

Inoculated smallpox was less virulent than its natural form. Although survivors gained lifelong immunity, they were still at risk of infecting others. The danger epidemic outbreaks remained.

Many Christians believed that God had allowed smallpox to spread among people as a punishment for their sins. Inoculation constituted interference with God’s will.

In 1767, the Mozart family was in Vienna where smallpox had crippled the city. Leopold Mozart refused to have his children inoculated, preferring (as he wrote to a friend in February that year) to “leave the matter to the grace of God.”

Young Mozart went down with the disease, but fortunately recovered. Poets (like William Blake) and theologians used the metaphor “Job’s boils” in relation to the symptoms of smallpox (the Old Testament tale of Job being subjected to a series of trials to test his faith, including an affliction of boils from head to toe).

Others described themselves as “conscientious objectors,” arguing that any imposed practice violated their free will. Physicians were accused of “collaborating” with government. Their intentions were questioned.

Speculation spread that doctors performed new procedures for personal gain. Activists viewed their anti-inoculation campaign as a righteous cause, one that was dedicated to shielding the public from a perceived threat.

Boston & Quebec

War and disease have a long and wretched history. In the colonies during the late-eighteenth century, smallpox was spread by troop movements. The British army had an advantage.

In England, the disease had long been endemic and most of soldiers had experienced smallpox in childhood and were therefore immune. By contrast, colonists as well as Native and Black Americans were vulnerable.

Signs of smallpox became evident during the early days of the American rebellion. Isolated incidents had occurred around Boston in 1774; soon after, the disease took hold of the city itself.

The first armed battle took place in April 1775 and smallpox festered through the summer while the Continental Army was entrenched around Boston. General George Washington feared that the disease could decimate his forces.

If smallpox would spread, he wrote to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in late 1775, it would be “disastrous & fatal to our army and the Country around it.”

This anxiety pushed him into decisive action. Washington had personal experience of smallpox and understood the danger of the disease.

In the autumn of 1751, aged nineteen, he had accompanied his half-brother Lawrence who was suffering from tuberculosis on a “healing” trip to Barbados.

Endemic in the Caribbean at the time, smallpox had been fairly uncommon in George’s Virginia. He had not contracted the disease as a child and was infected during the trip. Having survived the ordeal, he gained immunity. The fearful memory lasted.

Washington realized that it was impossible for his troops to gather in numbers without smallpox running rampant. Quarantine had some impact, but at times of military action such intervention was not feasible. He and his medical team decided to oversee a campaign of inoculating the entire army. It was arguably the most drastic decision that General Washington ever took.

The effort to control smallpox amongst his soldiers in Boston did pay off. The situation in Quebec was much worse. Throughout the siege of the Canadian city, American troops had to contend with an outbreak of smallpox.

On May 6, 1776, after a five-month fruitless battle, more than 1,500 soldiers fled up the St. Lawrence River as British regulars disembarked to relieve the Quebec garrison. In a chaotic withdrawal, all precautions to fight off the disease were ignored.

Five days later, soldiers began arriving at Sorel, a town where the Richelieu River enters the St. Lawrence. The presence of so many diseased men was a terrifying sight.

The approach of British troops forced what was left of the “Northern Army” to continue its retreat along the Richelieu River, eventually pausing at Île aux Noix, a small island near the north entrance of Lake Champlain.

The shattered army spent ten days there; most men were infected, there were few health care providers and no facilities to treat the diseased. Two mass graves were dug where more than nine hundred smallpox victims were buried.

The island was hell on earth. The bitter memory would last and impact an urgent search for ways of fighting the disease.

[Victims of smallpox from another large military hospital at Fort George in Lake George have recently been exhumed and are slated for reburial soon.]Smallpox Raids

Foreigners tend to be held responsible for epidemics or pandemics. In the 1800s, Irish immigrants were blamed for bringing cholera to the United States, Italians for polio, and Jews for tuberculosis.

During the 1900s, Chinese incomers were accused of spreading the bubonic plague in San Francisco. This blame-game seems timeless and is played today in discussions on the origin of COVID.

Panic about epidemics caused scapegoating with the associated consequences of prejudice, social exclusion and discrimination.

George Washington’s approach succeeded as it decreased the mortality rate amongst soldiers and restored his army’s ability to continue the battle. His policy of forced inoculation may have paved the way for modern vaccination policies, but the practice created a new set of problems.

The idea of compulsory vaccination met with strong opposition. Washington’s intervention worked because it was restricted to a specific group in a specific military setting. Applied in wider society, it was inevitable that minority groups would be targeted.

An epidemic of infectious disease proved not just to be a challenge to the medical system, it also provoked social stigma as it secluded groups of individuals from mainstream society.

Racism played its part. Minority groups, mostly African-Americans or immigrants, were blamed for epidemics. The geographic concentration of segregated racial groups enabled coercive targeting programs.

Smallpox (according to a retrospective investigation) was imported into Kentucky from Honduras in the summer of 1897. At the outset, the disease was noted as limited to the “colored” race.

The first case in the town of Middlesboro was identified early in December that year. Intervention failed due to a lack of medical facilities, denial by the authorities, and ignorance amongst the local population.

The disease spread rapidly, resulting in the most severe epidemic the State had ever known.

Measures were driven by panic. Groups of police and health officials entered an African-American section of town to forcefully vaccinate men and women. Those who resisted were treated at gunpoint. Such smallpox raids were not unusual.

Blauvelt in Italian Harlem

Although the first vaccine was developed in May 1796 by Edward Jenner, an English country doctor (the “Godfather of Vaccination”), smallpox remained rampant and was responsible for as many as 300 million deaths in the twentieth century alone.

Although the first vaccine was developed in May 1796 by Edward Jenner, an English country doctor (the “Godfather of Vaccination”), smallpox remained rampant and was responsible for as many as 300 million deaths in the twentieth century alone.

An epidemic was the Apocalypse made real. It divided communities, disregarded boundaries and shattered social cohesion.

In 1901, New York City experienced an outbreak of smallpox, particularly affecting immigrant communities in Italian Harlem. The city’s health department responded with aggressive measures and singled out these districts of dense immigrant populations as “suspect.”

On a Friday night in February of that year, more than two hundred police officers and health officials led by Alonzo Blauvelt, Chief Inspector of the Board of Health, blocked the roofs, entrances and backyards of every tenement block in East Harlem’s over-populated Italian neighborhood between 106th and 115th Streets.

In a carefully planned raid, they entered every apartment without warning, preventing terrified tenants from running away.

If in good health, residents were forcefully vaccinated. Those who showed symptoms of infection, be they children or adults, were separated from their families and transported to the East River docks.

If in good health, residents were forcefully vaccinated. Those who showed symptoms of infection, be they children or adults, were separated from their families and transported to the East River docks.

From there they were ferried to North Brother Island, just south of the Bronx, where a complex of quarantine hospitals had been erected. The island was associated with the notion of the “pest house.” Mere mention of the name made New Yorkers freeze with anxiety.

During the nineteenth century hospitals were not equipped to deal with contagious diseases. Patients were quarantined in isolation buildings known as pest houses.

Numerous stories were reported of mothers fighting with health officials to keep their sick children in their own care, rather than have them be taken away. Pest houses were associated with the horrors of suffering and death.

To this day, the term functions as a potent (literary) metaphor for various societal ills, connoting contamination, exclusion, isolation and social breakdown.

Although a vaccine had been developed for smallpox, many citizens did not heed warnings, refused to get vaccinated, or were unable to access facilities. From the very start of organized vaccination campaigns, there had been public resistance.

Blauvelt and his colleagues continued their task systematically. Tenants of homeless shelters, factory workers, members of the police force were all called out to be vaccinated. The approach was ruthless; the means applied were controversial.

Good ends can be achieved only by the employment of appropriate means. In his crusade for restoring public health, Blauvelt confused the means with the end.

His campaign deteriorated into actions that were cruel and oppressive. Brute intervention led to mistrust of public health measures, fueling “vaccine hesitancy” which, in turn, increased the risk of preventable disease outbreaks.

Other factors such as disinformation, unclear evidence, lack of access to health services, religious beliefs and/or individual prejudices contributed to this uncertainty.

In May 1980, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared smallpox to be eradicated, the first time in history that a deadly human disease was wiped out. For many social historians, it was a public health triumph.

Today, vaccination skepticism has become a topic of renewed controversy in American politics.

Fostering trust in public health efforts remains therefore imperative, as is the urgent need to find a way of putting government mandates in practice without compromising individual liberties.

[Editor’s Note: Florida Republicans announced Wednesday that they will “work to phase out all childhood vaccine mandates in the state” according to the Associated Press. “On the vaccines, state Surgeon General Dr. Joseph Ladapo cast current requirements in schools and elsewhere as an ‘immoral’ intrusion on people’s rights bordering on ‘slavery,’ and hampers parents’ ability to make health decisions for their children.”]Read more about smallpox in New York State.

Illustrations, from above: Young Vito Corleone in smallpox isolation on Ellis Island staring at the Statue of Liberty (still from The Godfather II); Justus Sustermans, “Portrait of Ferdinando II de’ Medici on the ninth day of smallpox,” 1626. (Galleria Palatina, Florence); Detail of James Northcote’s “Portrait of Edward Jenner,” 1803 (National Portrait Gallery, London); and one of the boys was vaccinated in infancy; the other was not (Photograph by Allan Warner).

Source link