The Returned Captive: Jonathan Dore

The story of sieges and massacres of soldiers at Fort William Henry in August 1757 and two years later to residents of the Indigenous village of St. Francis (Saint-François-du-Lac, a community in Quebec, Canada, also known as Odanak by the Abenaki), are well-known by those with even a casual interest in the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

The story of sieges and massacres of soldiers at Fort William Henry in August 1757 and two years later to residents of the Indigenous village of St. Francis (Saint-François-du-Lac, a community in Quebec, Canada, also known as Odanak by the Abenaki), are well-known by those with even a casual interest in the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

The story of Jonathan Dore is a small, but interesting tale of capture and self-redemption. His actions during both of those events shed a little more light on their impact on the individuals caught in this harrowing conflict.

If you drive on New Hampshire Route 108 from Dover into Rochester and look carefully to your left, you may notice, buried in the weeds, a small memorial to the events that transpired there in June 1746 during King George’s War (1744-1748).

If you drive on New Hampshire Route 108 from Dover into Rochester and look carefully to your left, you may notice, buried in the weeds, a small memorial to the events that transpired there in June 1746 during King George’s War (1744-1748).

To quote from an 1866 Adjutant General’s Report:

“The fall of Louisbourg [the year before] exasperated the French in Canada, and their Indian allies made no less frequent attacks on our frontier settlements. In fact, the year of 1746 is noted for the attacks by the Indians on the Provence [sic] of New Hampshire… Indians were constantly patrolling”

As a result of this threat, surveillance parties were constantly sent out from various local settlements, including a patrol from Rochester.

The Rochester of the 18th Century was typical of settlements on the edge of the frontier, with settlers eking out an existence. The 1742 Estate List of Philip Dore (Jonathan’s father) is typical for a Rochester resident. He is listed as possessing “1 pols (poultry?), 1 ox, 2 cows, 1 horse, 1 swine, 3 plantings and 1 house.”

On June 27, 1746, French-aligned Indians struck Rochester. Written in A Book of Records of the Church of Christ in Rochester is the following:

“June 27th 1746 Joseph Heard, John Wentworth and Gersham Downs were killed by the Indians on the main r

oad about two miles from the foot of the town. At the same time and place John Richards was wounded and captivated and on the same day Jonathan Door [sic], a young lad was captivated by the Indians at Salmon Falls Road in Rochester.”

oad about two miles from the foot of the town. At the same time and place John Richards was wounded and captivated and on the same day Jonathan Door [sic], a young lad was captivated by the Indians at Salmon Falls Road in Rochester.”

The journal of William Pote Jr. offers the first-hand account of John Richards “who was taken by the Indians at a place called Rochester in ye province of Newhampshire [sic]. He gave us an account there was four men and a boy killed when he was taken and himself wounded”

Nehemiah How’s narrative provides more details. “July 21 John Richards and a boy of nine or ten years old belonged to Rochester in New Hampshire, were brought to prison and told us there were four Englishmen kill’d when they were taken.”

Nothing more is heard about Jonathan Dore until after the conclusion of King George’s War and the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. The Boston Post-Boy on July 10, 1749 included this announcement:

“Mr. Timothy Brown, were he had been with some others to endeavor to redeem some Captive Children… there is also a boy who was taken from Rochester in New Hampshire with the Indians at St. Francois, his name is Jonathan Dore.”

In 1749 Massachusetts Colonial Governor William Shirley sent Phineas Stevens to recover whatever prisoners were held there, either by the French or Indigenous people. Two attempts to ransom Jonathan were unsuccessful.

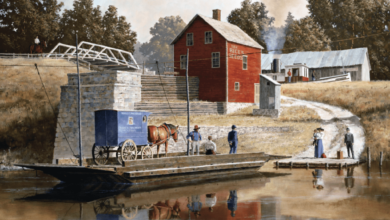

Jonathan Dore’s name resurfaces eight years later, with the surrender of Fort William Henry. On August 10, 1757, as New Hampshire troops were the last regiments to march out of the surrendered site, they were attacked by St. Francis Indians, and their column disintegrated.

Some sought protection from their English brethren, while others ran into the adjoining forest. Dore, one of the attacking tribal warriors, chased a New Hampshire soldier into the woods.

About to bring his hatchet down after catching his prey, he recognized the soldier as a man who had done business with his father and spared the soldier’s life.

The man Dore saved eventually returned to Dover and told people of being spared by Dore. My research over the last several years, going through records and muster rolls from the hometowns of these soldiers, shows that it’s likely the spared soldier was William Randal. In 1757 Randal was 52 years old, from Dover, and a farmer — someone fellow-farmer Philip Dore would likely have known.

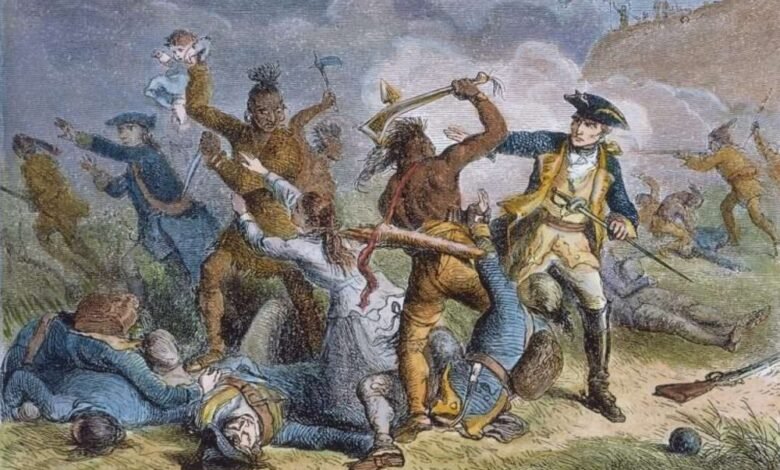

By the summer of 1759, the tide of the French and Indian War had decidedly turned in favor of the British. Having taken control of Lake George and the southern portions of Lake Champlain, Robert Rogers and a force of 150-200 troops departed Crown Point on September 10 with orders to destroy

the Abenaki village of St. Francis in the French province of Canada.

Arriving on October 4, Rogers and his forces fulfilled their mission, decimating the community in which Dore was residing.

For whatever reason —perhaps due to the deaths of his Abenaki family – Dore returned to Rochester in December, only to find that his New Hampshire relatives had moved across the Salmon Falls River into what is now Lebanon, Maine.

For whatever reason —perhaps due to the deaths of his Abenaki family – Dore returned to Rochester in December, only to find that his New Hampshire relatives had moved across the Salmon Falls River into what is now Lebanon, Maine.

The diary of Thomas Moody, a lieutenant in Captain Wentworth’s company in Berwick (modern-day Maine), shows Jonathan Dore enlisted as a private in that regiment in May 1760.

The group moved along the customary military campaign route of the time, through Albany and Fort Edward, past the ruins of Fort William Henry at the head of Lake George, past Forts Ticonderoga and Crown Point on Lake Champlain, into Canada.

There are two mentions of Dore during this campaign near Isle Aux Noix and St. John. The first is from Moody’s entry on Friday, August 22. “This day 2 prisoners were brought in from St. John by Jon. Dore and 5 or 6 of the Light Infan[try]”.

At this time, Dore may have been acting as a Ranger, for in a diary by Lt. J.M. Bradbury it states “Jonathan Door went out with 8 of the light infantry and in 4 days brought in three persons for which Col. Haverland gave him 32 dollars, besides other things.”

Moody’s diary also indicates that Dore was released from service in October 1760, ahead of the rest of his company. Massachusetts General Court records contain this entry: “Jonathan Dore of Berwick, to attend this House as soon as may be.”

On June 26, 1761, a “Committee of Inquiry ordered, that Mr. Welles, Major Hartwell, Capt. Howard, Capt. Livermore and Mr. Bradbury examine Jonathan Dore, respecting the nearest route to the country of Canada and report.”

The Committee reported back on June 27: “The Committee appointed to consider what was proper to be granted to Jonathan Dore, lately returned to captivity made a report. Read and accepted and ordered, that the sum of thirteen pounds be granted and allowed to be paid out of the public treasury to said Jonathan Dore, in consideration of his services and suffering in captivity and his journey to Boston to wait upon this House according to the order.”

Dore married Dorothy Farnum and they had no children, but adopted John Dixon. He had one more service for his country.

In September 1776, the New Hampshire House of Representatives resolved that “James Knowles and George Place of Rochester should serve as a committee and visit Jonathan Dore of Lebanon and desire that he would show them the lead mine lately discovered by him.”

Despite Jonathan Dore’s permanent return to the place of his childhood, he never fully gave up the Indigenous ways he was taught at St. Francis, and was known locally in his later years as “Indian Dore.”

Jonathan Dore died in 1799 and is buried in an unmarked grave in Lebanon, Maine.

Alan Stone received a BA in History from the University of New Hampshire and Social Studies Teaching credentials from Franklin Pierce College. He is a retired high school Advanced Placement-American History teacher and a retired CWO4 from the US Coast Guard Reserve. He is a member of the Lake George Battlefield Park Alliance, Friends of Fort Ticonderoga, Fort Plain Museum, Montgomery County Historical Society, Mayflower Society, and Sons of the American Revolution.

A version of this essay was first published in the Fort George Post, The Journal of the Lake George Battlefield Park Alliance. The Lake George Battlefield Park Alliance is a not-for-profit organization of volunteers who have an abiding interest in the Lake George Region’s critical role in the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. For more information, visit www.lakegeorgebattlefield.org.

Illustrations, from above: a fictionalized portrayal of the massacre at Fort William Henry in 1757; historical marker memorializing the June 1746 attack on Rochester, NH; Blanchard and Langdon’s 1761 map of New Hampshire showing the path captives were carried to New France (Library of Congress, see a larger version here); and the same map showing the Rochester, NH area.

Source link