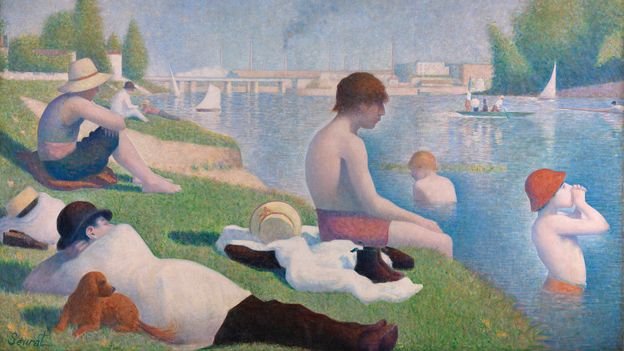

The radical manifesto hidden in Georges Seurat’s 1884 masterpiece

From its inception, Seurat was determined that Bathers at Asnières would not be just another painting. It was an audacious manifesto on how we see the world when the artificial trappings of class and status, form and function, are filtered away to reveal the vital vibration of colour, pure colour – a meticulously plotted statement of purpose and artistic intent. In preparation for the work, Seurat dramatically departed from Impressionist spontaneity and its habit of working hastily outdoors, undertaking in his studio more than a dozen oil sketches and nearly as many crayon drawings, convinced this would be the masterwork that established his place in the art world. Bathers, he believed, would be the painting that people noticed – the one he could confidently submit to the famously implacable jury of the influential Salon, the institution whose stingy regard, if secured, could determine the career prospects of any aspiring artist. So he submitted it. And they rejected it.

More like this:

• The WW2 poster that became a loved and hated icon

• The US statue at the heart of a culture war

• The real meaning of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers

While widely admired today as a masterpiece of evocative atmospherics, Bathers at Asnières’ road to critical acclaim was a bumpy one at best. Bruised but unbeaten by the Salon’s rejection, Seurat remained determined that his canvas would still be seen. He soon joined forces with a plucky band of equally aggrieved rejects from the persnickety Salon that included Paul Signac and Odilon Redon. Calling themselves the Groupe des Artistes Indépendants, the crew hastily staged a rival exhibition in a makeshift wooden pavilion, near the Place de la Concorde. Unfortunately for Seurat, the incommodious size of his canvas and the organisers’ decision to cram the rough-and-ready walls with more than 400 works, resulted in his work being elbowed into an unglamorous spot in the show where it was met with befuddlement by the few who took any notice of it at all. Though one early reviewer of the painting showed restraint, insisting that he didn’t “quite dare poke fun at it”, another felt no compunction in calling it “monstrous”, “vulgar”, and “bad from every point of view”.

It would be another half-a-century, and long after Seurat himself would die prematurely in March 1891 at the age of just 31, that his masterpiece would begin to be seen as a significant moment in the story of art. After languishing in private hands for 60 years, Bathers was acquired in 1924 by the Tate Gallery in London, elevating its profile. Positioned properly on a museum wall, with ample space for visitors’ eyes to absorb its power, Bathers at Asnières began to gain critical traction both for its exquisite distillation of the very essence of summer and as a modern wonder in the art of seeing.

Bathers at Asnières is on display at The National Gallery in London.

Source link