The Educational Legacy of Lucretia Foot Booth

Lucretia Foot Booth was born in 1804 in Troy, NY, the only child of Ebenezer Foot and Betsey Colt Foot. She grew up in a household deeply committed to education. Lucretia inherited a dedication to learning and supporting educational equality for girls, ensuring they received a parallel education from those of their male counterparts.

Lucretia Foot Booth was born in 1804 in Troy, NY, the only child of Ebenezer Foot and Betsey Colt Foot. She grew up in a household deeply committed to education. Lucretia inherited a dedication to learning and supporting educational equality for girls, ensuring they received a parallel education from those of their male counterparts.

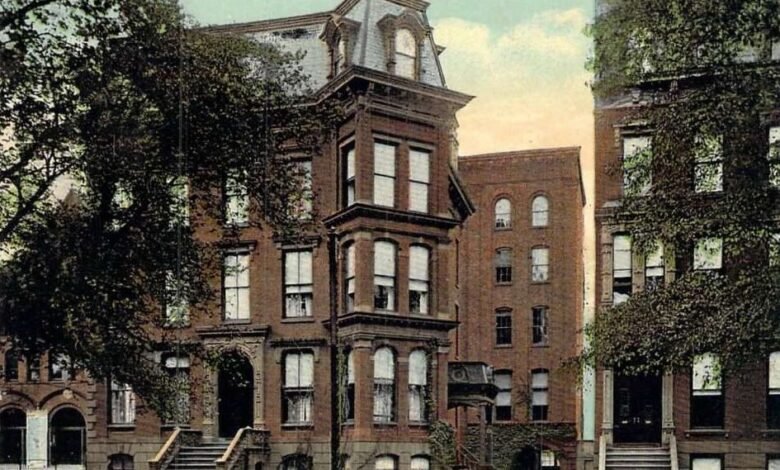

Her efforts mirrored her mother’s actions, whose vision for academic accessibility led to the charter created for the Union School for Girls in Albany, NY, which became The Albany Academy for Girls, when it opened in 1814 as a pioneering seminary dedicated to offering young women the same academic opportunities as young men (now Albany Academy).

Betsey recognized the significant disparities in academic opportunity and urged Ebenezer, a prominent lawyer, to create the school’s charter. According to a family historian, their shared belief was that “girls and women are not only deserving of higher education but fully capable of leading intellectually and socially engaged lives.”

Betsey recognized the significant disparities in academic opportunity and urged Ebenezer, a prominent lawyer, to create the school’s charter. According to a family historian, their shared belief was that “girls and women are not only deserving of higher education but fully capable of leading intellectually and socially engaged lives.”

In the 19th century, the word seminary denotes institutions dedicated to higher learning for women, and is not based on religious education. Female seminaries focused on teaching young women subjects such as philosophy, science, arithmetic, and literature. Some seminaries grew into colleges and universities, serving as critical stepping stones in the movement toward women’s educational equality.

The name Lucretia held deep familial significance, passed down through multiple generations, carried by both ancestors and descendants alike. Ebenezer Foot’s lineage traced back to Mary Peck and Captain John Foot, while Betsey Colt Foot’s heritage was rooted in Benjamin Colt and Lucretia Walker.

Both the Foots and Colts were prominent in society. The Albany Institute of History & Art holds a painting of Lucretia Foot as a child by nd the National Portrait Gallery holds a portrait of Betsey Colt Foote by Ezra Ames, testaments to the social status of the family.

The men in the families were educators, lawyers, and judges. Both families emigrated from England during the colonial period. The wealth and prestige of the Foots provided them with the ability to send their male children to study law or higher education.

In 1821, Lucretia Foot married Lebbeus Booth, who would establish the Ballston Spa Female Seminary in 1824. Inspired by her mother’s unwavering commitment to education, Lucretia urged Lebbeus to open the seminary, ensuring that young women had access to the same academic instruction that she had.

Though severely overlooked by history, Lucretia’s steadfast advocacy left a lasting mark, shaping opportunities for generations of young women.

Despite her pivotal role, an article detailing the school’s founding credited only Lebbeus, noting that forty women were initially enrolled. However, both Lucretia and Lebbeus were actively involved in shaping the seminary, overseeing its operations, and developing its curriculum to provide students with a comprehensive education.

Lebbeus Booth dedicated his career to education and public service in Saratoga County, contributing to both civic and religious institutions. A committed member of Christ Episcopal Church, he served as loan commissioner and later became County Superintendent of the Poor in 1844.

His leadership extended into financial and community organizations, holding the position of Vice President of the Ballston Spa National Bank and president of the Saratoga County Bible Society.

Lucretia and Lebbeus had twelve children, seven of whom died before entering adulthood. Elizabeth, their first child, and daughter, lived fifteen years.

Lucretia and Lebbeus had twelve children, seven of whom died before entering adulthood. Elizabeth, their first child, and daughter, lived fifteen years.

Their first-born son, Moss Kent, was a Commencement Orator. He was the principal of the public school in Southington, CT. After he passed the bar exam, he moved to Boston, where he practiced law and was a member of the Massachusetts Legislature. He moved back to Ballston Spa, where he lived for 30 years until his death.

Young son, John Chester, lived for nearly six years before passing away, a loss that began a tradition observed in the family — naming a subsequent child after one who had passed. When another son was born, he was given the name John Chester II.

John Chester II established a private school about two miles north of the village of Cranesville, in Montgomery County, NY. He became a successful attorney and also had an interest in history, compiling a detailed account of Saratoga County — a work he completed two years before his death.

John’s research was published posthumously when Edward F. Grose incorporated his history into Centennial History of the Village of Ballston Spain 1907. John died at 28, leaving behind his wife, Margaret, and their two daughters, Ella and Mattie (Martha). Tragically, Mattie soon succumbed to diphtheria at age seven.

Tragedy struck Lucretia’s family repeatedly. Infant son, Josiah Quincy, lived just over eight months. Infant daughter Martha died at three months, but her namesake Martha II grew up and married Lindsley Seelye in 1852.

Seelye’s family was one of the first citizens of Ballston Spa. Lindsley is credited to be a man of honor, prestige, and faith. Having suffered from consumption, the family spent the winters in New Orleans, and the rest of the year in Ballston Spa. Lindsley died young at 39, Martha lived on to 82.

Infant daughters, Mary Lucretia, and Mary Lucretia II, both died before their second birthday. Young adult, Isabella “Belle” died at 17 from a contagious fever, while attending Troy Seminary. She was to be part of the graduating class of 1856. She never graduated.

Daughter Lucretia married the Reverend George Washington Dean S.T.D. He was the chaplain and instructor of Latin and metaphysics in St. Agnes’ School, and alumni “professor of the evidence of revealed religion” in the General Theological Seminary in the city of New York.

He founded the St. Stephen’s college at Annandale-on-Hudson, in Dutchess County, now known as Bard College. For six years he was rector of Christ Church, Ballston Spa. and later was rector of St. Stephen’s Church, at Schuylerville, until his death in 1880. Lucretia II died from pneumonia at 86.

Lucretia by following her mother’s influence, inspired her own dedication to educational equality. Both Betsey and Lucretia married men who believed their wives should be by their side, not one step behind them.

She raised and mourned her children, remaining a woman of great strength and intelligence sharing the educational vision of her husband. Lebbeus died at 70 in 1859, with marasmus (malnutrition) cited as the cause of death.

Lucretia lived another 13 years and died in Ballston Spa at the age of 67, in 1872. Lucretia and her family are buried in the Ballston Spa Village Cemetery, in the Booth family plot.

Read more about the history of education in New York State.

Amy Shannon, an Upstate New York storyteller who runs the book review site Amy’s Bookshelf Reviews and a writer’s blog. She is the author of Balls-Town: A Community of History, Friends, Neighbors, and Lingering Spirits (2024), which emphasizes the importance of preserving local history.

This essay is presented by the Saratoga County History Center. Follow them on Twitter and Facebook.

Illustrations, from above: Illustrations, from above: Albany Academy for Girls postcard, ca. 1900; Lucretia Foot Booth, after an unknown portrait; and Betsey Colt Foot by Ezra Ames (National Portrait Gallery).