The 1960 Battle of the Bateaux

A piece of a 1758 bateau retrieved from the bottom of Lake George, displayed under glass at the Lake George Battlefield Park Visitors Center, is the only visible remains of the Battle of the Bateaux of 1960.

A piece of a 1758 bateau retrieved from the bottom of Lake George, displayed under glass at the Lake George Battlefield Park Visitors Center, is the only visible remains of the Battle of the Bateaux of 1960.

If one goes by contemporary newspaper accounts, that battle was as vicious – though not quite as deadly – as the French and Indian War (1754-1763) itself.

William Pitt, Britain’s wartime leader, ordered the flat-bottomed boats to be built for the campaign that would ultimately end in the capture of Quebec and the expulsion of the French from North America.

In the winter of 1758-59, however, they lay at the bottom of the frozen lake, deliberately scuttled, protected from the enemy.

There, roughly 40 of them remained, more or less undisturbed, until 1960, when two young divers – Robert LaVoy of Glens Falls and Fred Bolt of Lake George – came upon them while exploring the waters off Hall’s boatyard.

In something of an understatement, The Warrensburg News noted, “the flotilla of Colonial war boats… is believed to have much genuine archaeological value.”

New York State’s Department of Education claimed jurisdiction over the wrecks, and after discussions with the divers and their lawyers, the Warren County Sheriff’s Department, Fort William Henry and the Adirondack Historical Association (aka the Adirondack Museum, now known as Adirondack Experience), the state awarded the Adirondack Museum and its director, Dr. Robert Bruce Inverarity, a permit to raise several of them.

New York State’s Department of Education claimed jurisdiction over the wrecks, and after discussions with the divers and their lawyers, the Warren County Sheriff’s Department, Fort William Henry and the Adirondack Historical Association (aka the Adirondack Museum, now known as Adirondack Experience), the state awarded the Adirondack Museum and its director, Dr. Robert Bruce Inverarity, a permit to raise several of them.

The Battle of the Bateaux was on. “Shall historic objects found in Lake George go to museums elsewhere?” the Lake George Mirror demanded to know.

In the first of several blasts and broadsides, editor Art Knight wrote that however qualified Dr. Inverarity of “the so-called Adirondack Historical Association” might be in some fields (he was, for instance, an internationally renowned expert on the art of the indigenous peoples of the North Pacific coast) he knew nothing about Lake George.

Moreover, the focus of his museum was “totally unrelated to the pre-historical and pre-colonial and post-historical and post-colonial eras which Lake George and Lake Champlain represent.”

Gathering steam, Knight added, “any Adirondack association should be superceded by the Lake George Association in supervising or directing the disposition of objects recovered from the lake.”

Col. Edward P. Hamilton, director of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum, accused the Adirondack Museum of “trespassing.” In a letter to Dr. James E. Allen, the state Commissioner of Education, Hamilton argued that the permit awarded the Adirondack Museum was “something to which they are not entitled and which does not pertain to the field in which they operate.”

Obviously relishing a good fracas, The Ticonderoga Sentinel reported that “garrisons of the forts in the Lake Champlain basin are gathering ammunition in preparation for action to repel invaders.”

Learning that Dr. Inverarity was readying a reply to his critics, the Sentinel wrote, “war drums continue to pound out their messages, as the director of the Adirondack Museum prepares to respond to the signals sent out earlier by Col. Hamilton.”

It was left to Dr. Inverarity to calm the roiled waters. First, he explained that the Lake George and parts of the Lake Champlain watersheds were indeed within the Adirondack Park and thus of legitimate interest to the museum.

Moreover, he reminded (or perhaps informed) his critics that since 1955, the museum had been researching the small craft of the Adirondacks, in particular, the guide-boat.

“Our research files include two drawings of colonial bateaux, in which we see a relationship to some of the craft in our collection. This is the origin of our interest in the bateaux found in Lake George,” Inverarity wrote in a letter that was printed in the Lake George Mirror.

“Our research files include two drawings of colonial bateaux, in which we see a relationship to some of the craft in our collection. This is the origin of our interest in the bateaux found in Lake George,” Inverarity wrote in a letter that was printed in the Lake George Mirror.

Kenneth Durant, whose authoritative The Adirondack Guide-Boat, which the Adirondack Museum published in 1980, was indeed curious about a possible link between the 18th century bateau and the guide-boat – a curiosity that drew him and his wife and co-author, Helen Van Dongen Durant, to Lake George to inspect the boats as they were being raised.

I know that for a fact because they used the occasion to visit my family, whom they had known since the 1940s.

The Lake George Mirror and Fort Ticonderoga were under the impression that the permit awarded the Adirondack Museum gave it undisputed rights to “all artifacts found on the lake bottom.”

And rather than having a scholarly interest in whatever lay at the bottom of the lake, the Adirondack Museum, according to the Lake George Mirror, viewed it as “loot,” to be displayed “in a museum away from this lake.”

Inverarity took pains to disabuse the Lake George Mirror and Fort Ticonderoga of those notions.

“Our object is not to acquire booty but to help in the advancement of historical knowledge,” Inverarity wrote. “We shall be content with any disposition the state may make of items found in the lake. It is unwarranted to assume that any one institution or museum will benefit at the expense of others.”

Walter Ruth, president of the Fort William Henry Corporation, explained to Art Knight why the Adirondack Museum, rather than Fort William Henry, was chosen by the State Education Department to recover the boats:

“At the time, Fort William Henry lacked the resources and special skills required for the task.” According to Ghost Fleet Awakened: Lake George’s Sunken Bateaux of 1758,” Joseph W. Zarzynski’s history of the bateaux and their afterlife, “the disagreement between the museums died down, eventually. Lake George’s hometown newspaper, the Lake George Mirror, would become – and still is today — one of the staunchest supporters of historic preservation issues concerning the ‘Queen of American Lakes.’”

“At the time, Fort William Henry lacked the resources and special skills required for the task.” According to Ghost Fleet Awakened: Lake George’s Sunken Bateaux of 1758,” Joseph W. Zarzynski’s history of the bateaux and their afterlife, “the disagreement between the museums died down, eventually. Lake George’s hometown newspaper, the Lake George Mirror, would become – and still is today — one of the staunchest supporters of historic preservation issues concerning the ‘Queen of American Lakes.’”

Zarzynski, a marine archaeologist, historian, documentarian and preservationist who contributes regularly to New York Almanack, says that Inverarity’s “Operation Bateaux” was one of the first professionally conducted underwater archaeological study of shipwrecks in the United States.

Three bateaux were recovered from the lake by Inverarity’s team and transported to the Adirondack Museum, where they were treated with polyethylene glycol (PEG), a wood preservative. One bateau was placed on display, where it remained until returned to New York State, its proper owner.

According to Zarzynski, the three bateaux retrieved from the lake, and a collection of disarticulated remnants also found in the lake, are now in the collections of the New York State Museum. The fragment on display at the Lake George Visitor Center is on loan from the state.

Inverarity left the Adirondack Museum in 1965, returning to the eastern US a few years later to lead the Philadelphia Maritime Museum. But with his departure from the Adirondacks, “Operation Bateaux” fell dormant, and would remain so for more two decades, until Zarzynski and Dr. Russell P. Bellico organized a three-day underwater archaeology workshop in Lake George.

“After two days of instruction, the third day had about 20 scuba enthusiasts diving on a cluster of several sunken bateaux called the Wiawaka Bateaux,” Zarzynski said.

“After two days of instruction, the third day had about 20 scuba enthusiasts diving on a cluster of several sunken bateaux called the Wiawaka Bateaux,” Zarzynski said.

Shortly thereafter, Zarzynski and Bellico founded the nonprofit organization Bateaux Below, which for the next quarter century mapped Lake George’s shipwrecks and monitored them to make certain they were never vandalized.

Thanks to Bateaux Below, seven of the sunken bateaux of 1758 were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992. A year later, they became part of an underwater state park for divers — Lake George’s Submerged Heritage Preserve.

A version of this article first appeared on the Lake George Mirror, America’s oldest resort paper, covering Lake George and its surrounding environs. You can subscribe to the Mirror HERE.

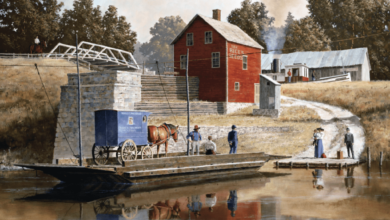

Illustrations, from above: A computer-generated image of the bateaux shortly after they were sunk in 1758 (image by John Whitesel, courtesy of Pepe Productions); Dr. Robert Bruce Inverarity, director of the Adirondack Museum with a bateaux recovered from Lake George in 1960; a drawing of a colonial bateau by Mark Peckham, courtesy of Bateaux Below; a 1960-raised 1758 Lake George bateau on exhibit at the Adirondack Museum (photo of Dr Russ Bellico, Bateaux Below); and the “Sunken Fleet” historic sign on Beach Road in Lake George.

Source link