Sports and Amusements in Old New York

In the middle of the eighteenth century we find that New Yorkers were fond of all kinds of sports and all kinds of amusements that were available. The city was making rapid strides in increase of wealth and population. Many of her wealthy merchants had built large and handsome houses and there was more gaiety and desire for entertainment among her people.

In the middle of the eighteenth century we find that New Yorkers were fond of all kinds of sports and all kinds of amusements that were available. The city was making rapid strides in increase of wealth and population. Many of her wealthy merchants had built large and handsome houses and there was more gaiety and desire for entertainment among her people.

For balls, banquets, social clubs and exhibition of all sorts, each tavern of importance had, if possible, its “long room.” There was no other provision or place for public assemblage. Some had delightful gardens attached to them, which, in summer evenings, were illuminated and sometimes the guests were entertained with music.

Boating and fishing were largely indulged in and people of means who lived on the waterside had pleasure boats. In 1752 John Watson was keeping the Ferry House on Staten Island.

In December of that year “a Whale 45 feet in length ran ashore at Van Buskirk’s Point at the entrance of the Kills from our Bay, where, being discovered by People from Staten Island, a number of them went off and Killed him.”

Mr. Watson states in an advertisement in the New York Gazette of December 11, 1752, that this whale may be seen at his house, and doubtless this announcement may have induced many to make the trip across the bay to see the whale and add to the profits of John Watson’s tavern.

The Reverend Mr. Burnaby, who visited the city about 1748, says:

“The amusements are balls and sleighing expeditions in the winter, and in the summer going in parties upon the water and fishing, or making excursions into the country. There are several houses, pleasantly situated up the East River, near New York, where it is common to have turtle feasts. These happen once or twice a week.

“Thirty or forty gentlemen and ladies, meet and dine together, drink tea in the afternoon, fish and amuse themselves till evening, and then return home in Italian chaises (the fashionable carriage in this and most parts of America), a gentleman and lady in each chaise.”

These trips up the East River were made to Turtle Bay. One of the houses there about this time, or a little later, was well known as the Union Flag, situated on the post road.

A lot of about 22 acres of land was attached to the tavern, extending to the river, on which was a good wharf and landing. Deep drinking and gambling were prevalent among the men, although tavern-keepers were forbidden by law from permitting gambling in their houses.

Cock-fighting was a popular sport. At the sign of the Fighting Cocks — an appropriate sign — in Dock Street, “very good cocks” could be had, or at the Dog’s Head in the Porridge Pot. Steel and silver spurs could be purchased in the stores. The loser of a broad cloth coat advertises in the newspaper that it was lost on a cockfighting night (supposed taken by mistake).

Cock-fighting was a popular sport. At the sign of the Fighting Cocks — an appropriate sign — in Dock Street, “very good cocks” could be had, or at the Dog’s Head in the Porridge Pot. Steel and silver spurs could be purchased in the stores. The loser of a broad cloth coat advertises in the newspaper that it was lost on a cockfighting night (supposed taken by mistake).

The Common was a place where outdoor games were played in the daytime and bonfires built at night on festive occasions. On Monday, April 29, 1751, a great match at cricket was played here for a considerable wager by eleven Londoners against eleven New Yorkers.

The newspaper account states that “The Game was play’d according to the London Method; and those who got most Notches in two Hands, to be the Winners:—The New Yorkers went in first and got 81; Then the Londoners went in and got but 43; Then the New Yorkers went in again and got 86; and the Londoners finished the Game with getting only 37 more.”

The game of bowls [a type of ground billiards similar to croquet] seems to have been quite popular in the early part of the eighteenth century. It was played upon a smooth, level piece of turf from forty to sixty feet square, surrounded by a ditch about six inches deep.

At the further end of the ground was placed a white ball called the jack and the bowlers endeavored, with balls from six to eight inches in diameter that were not exactly round but weighted on one side so as to roll in a curve, to make their balls lie as near to the jack as possible.

Backgammon was an evening game at the taverns and at the coffee-house. In 1734 a partisan of the governor’s party, under the nom de plume of Peter Scheme wrote in reply to an article in Zenger’s Journal:

“I also frequent the Coffee House, to take a hitt at Back-Gammon, when I have an opportunity of hearing the curious sentiments of the Courtiers (since he is pleased to call the Gentlemen who frequent that place so) concerning his Journal.”

It is apparent that the popularity of the game continued for many years, for Alexander Mackraby, in a letter dated June 13, 1768, says:

“They have a vile practice here, which is peculiar to the city: I mean that of playing at back-gammon (a noise I detest), which is going forward at the public coffee-houses from morning till night, frequently a dozen tables at a time.”

Horse Racing

From the very beginning of English rule in New York, horse-racing seems to have been a fashionable sport among people of means. It has been stated how Governor Nicolls [Richard Nicolls, c. 1624 – 1672, was an English military officer and colonial administrator who served as the first governor of the Province of New York from 1664 to 1668] established a race-course on Hempstead Plains, and since that time interest in the sport had been kept up, increasing as the population and wealth of the city increased.

From the very beginning of English rule in New York, horse-racing seems to have been a fashionable sport among people of means. It has been stated how Governor Nicolls [Richard Nicolls, c. 1624 – 1672, was an English military officer and colonial administrator who served as the first governor of the Province of New York from 1664 to 1668] established a race-course on Hempstead Plains, and since that time interest in the sport had been kept up, increasing as the population and wealth of the city increased.

Races were held yearly on the Hempstead course and it is more than likely that a course was soon established on Manhattan Island. In 1733 we find an announcement in a New York newspaper that a race would be run on the 8th of October on the course at New York for a purse of upwards of four pounds by any horse, mare or gelding carrying twelve stone and paying five shillings entrance, the entrance money to go to the second horse if not distanced.

There is no mention made of the location of the course, but a notice that horses that have won plate here are excepted indicates that it was probably a yearly event. Three years later we find that a subscription plate of twenty pounds’ value was to be run for on the course at New York on the 13th of October “by any horse, mare or gelding carrying ten stone (saddle and bridle included), the best of three heats, two miles each heat.

“Horses intended to Run for this Plate are to be entered the Day before the Race with Francis Child on Fresh Water Hill, paying a half Pistole each, or at the Post on the Day of Running, paying a Pistole.”

This course on Fresh Water Hill had probably been established for some time and its location was very likely near the present Chatham Square [later known as Five Points, now in Chinatown].

In 1742 there was a race-course on the Church Farm [formerly known as King’s Farm, later the farm of the Trinity Church, though it may no longer have been owned by them, it was bounded by Fulton and Warren streets, Broadway and the Hudson River] in charge of Adam Vandenberg, the lessee of the farm, who was landlord of the Drovers’ Tavern, which stood on or near the site of the present Astor House [in 1915 still standing at the corner of Broadway and Vesey Street]. .

In seeking information from the newspapers of the day in regard to horse-racing, we find very little, if any, in the news columns; but more is to be found among the advertisements.

Thus, in January, 1743-4, it is announced that a race would be run on the first day of March “between a Mare called Ragged Kate, belonging to Mr. Peter De Lancey [1705-1770], and a Horse called Monk, belonging to the Hon. William Montagu, Esq., for £200.”

It is not stated where this race was to take place, but, in all probability, it was run either on the Fresh Water Hill course or on the Church Farm. It was for an unusually large wager, and, no doubt, attracted a great deal of attention.

It is not stated where this race was to take place, but, in all probability, it was run either on the Fresh Water Hill course or on the Church Farm. It was for an unusually large wager, and, no doubt, attracted a great deal of attention.

From about this date we hear no more of the race-course on Fresh Water Hill. It may have been disturbed by the line of palisades which was built across the island during the war with France, crossing the hill between the present Duane and Pearl Streets, at which point was a large gateway.

In September, 1747, it was announced in the newspapers that a purse of not less than ten pistoles [the French name given to Spanish gold coin] would be run for on the Church Farm on the 11th of October, two mile heats, horses that had won plate on the island and a horse called Parrot excepted, the entrance money to be run for by any of the horses entered, except the winner and those distanced.

We have every reason to suppose that the races were at this period a yearly event on the Church Farm, taking place in October.

In 1750 it was announced in the New York Gazette in August and September that “on the Eleventh of October next, the New York Subscription Plate of Twenty Pounds’ Value, will be Run for by any Horse, Mare or Gelding that never won a Plate before on this Island, carrying Ten Stone Weight, Saddle and Bridle included, the best in three Heats, two miles in each Heat,” etc.

A few days after the race the New York Gazette announced that on “Thursday last the New York Subscription Plate was run for at the Church Farm by five Horses and won by a horse belonging to Mr. Lewis Morris, Jun.”

The next year similar announcements were made of the race, the difference being that the horses eligible must have been bred in America and that they should carry eight stone weight. The date is the same as that of the previous year, October 11.

We find no record of this race in the newspapers, but the illustration which is given of the trophy won is sufficient to indicate the result. Lewis Morris, Jr.[1726-1798, a signer of the Declaration of Independence], appears to have carried off the prize a second time. The plate was a silver bowl ten inches in diameter and four and one-half inches high, and the winner was a horse called Old Tenor.

The name of the horse was doubtless suggested by certain bills of credit then in circulation in New York. In an advertisement of two dwelling houses on the Church Farm for sale in April, 1755, notice is given that “Old Tenor will be taken in payment.”

The name of the horse was doubtless suggested by certain bills of credit then in circulation in New York. In an advertisement of two dwelling houses on the Church Farm for sale in April, 1755, notice is given that “Old Tenor will be taken in payment.”

The great course was on Hempstead Plains. On Friday, June 1, 1750, there was a great race here for a considerable wager, which attracted such attention that on Thursday, the day before the race, upward of seventy chairs and chaises were carried over the Long Island Ferry, besides a far greater number of horses, on their way out, and it is stated that the number of horses on the plains at the race far exceeded a thousand.

In 1753 we find that the subscription plate, which had become a regular event, was run for at Greenwich, on the estate of Sir Peter Warren [1703-1752, a Vice-Admiral in the Royal Navy and politician who sat in the British House of Commons]. Land about this time was being taken up on the Church Farm for building purposes, and this may have been the reason for the change.

In 1754 there was a course on the Church Farm in the neighborhood of the present Warren Street. An account of a trial of speed and endurance was given on April 29, 1754. “Tuesday morning last, a considerable sum was depending between a number of gentlemen in this city on a horse starting from one of the gates of the city to go to Kingsbridge and back again, being fourteen miles (each way) in two hours’ time; which he performed with one rider in 1 hr. and 46 min.”

The owner of this horse was Oliver De Lancey, one of the most enthusiastic sportsmen of that period. Members of the families of DeLancey and Morris were the most prominent owners of race horses. Other owners and breeders were General Monckton, Anthony Rutgers, Michael Kearney, Lord Sterling, Timothy Cornell and Roper Dawson.

General Monckton [Lieutenant-General Robert Monckton, 1726 – 1782) a British Army officer, politician and colonial administrator], who lived for a time at the country seat called “Richmond,” owned a fine horse called Smoaker, with which John Leary, one of the best known horsemen of the day, won a silver bowl, which he refused to surrender to John Watts, the general’s friend, even under threat of legal process. Several years later he was still holding it.

In January, 1763, A.W. Waters, of Long Island, issued a challenge to all America. He says: “Since English Horses have been imported into New York, it is the Opinion of some People that they can outrun The True Britton,” and he offered to race the latter against any horse that could be produced in America for three hundred pounds or more.

This challenge does not seem to have been taken up until 1765, when the most celebrated race of the period was run on the Philadelphia course for stakes of one thousand pounds. Samuel Galloway, of Maryland, with his horse, Selim, carried off the honors and the purse.

Besides the course on Hempstead Plains, well known through all the colonies as well as in England, there was another on Long Island, around Beaver Pond, near Jamaica.

A subscription plate was run for on this course in 1757, which was won by American Childers, belonging to Lewis Morris, Jr. There were also courses at Paulus Hook, Perth Amboy, Elizabethtown and Morristown, New Jersey, which were all thronged by the sporting gentry of New York City.

James De Lancey, with his imported horse, Lath, in October, 1769, won the one hundred pound race on the Centre course at Philadelphia. The Stamp Act Congress of 1765 brought together in New York men interested in horse-racing who had never met before, and in the few years intervening before the Revolution there sprang up a great rivalry between the northern and southern colonies.

Bear and Bull Baiting & Bowling

The men of New York enjoyed rugged and cruel sports such as would not be tolerated at the present time. Among these were bear-baiting and bull-baiting. Bear-baiting became rare as the animals disappeared from the neighborhood and became scarce.

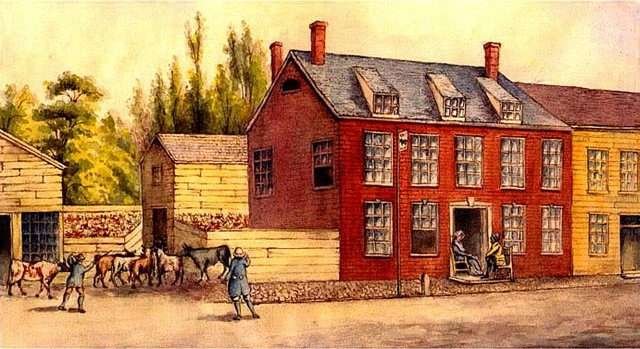

Bulls were baited on Bayard’s Hill and on the Bowery. A bull was baited in 1763 at the tavern in the Bowery Lane known as the sign of the De Lancey Arms. John Cornell, near St. George’s Ferry, Long Island, gave notice in 1774 that there would be a bull baited on Tower Hill at three o’clock every Thursday afternoon during the season.

Bulls were baited on Bayard’s Hill and on the Bowery. A bull was baited in 1763 at the tavern in the Bowery Lane known as the sign of the De Lancey Arms. John Cornell, near St. George’s Ferry, Long Island, gave notice in 1774 that there would be a bull baited on Tower Hill at three o’clock every Thursday afternoon during the season.

The taverns in the suburbs could, in many cases, have large grounds attached to the houses and they took advantage of this to make them attractive. From the very earliest period of the city there were places near by which were resorted to for pleasure and recreation.

One of the earliest of these was the Cherry Garden. It was situated on the highest part of the road which led to the north—a continuation of the road which led to the ferry in the time of the Dutch — at the present junction of Pearl and Cherry Streets, and was originally the property of Egbert Van Borsum, the ferryman of New Amsterdam, who gave the sea captains such a magnificent dinner.

In 1672 the seven acres of this property were purchased by Captain Delaval for the sum of one hundred and sixty-one guilders in beavers, and, after passing through several hands, became the property of Richard Sacket, who had settled in the neighborhood, and established himself as a maltster.

On the land had been planted an orchard of cherry trees, which, after attaining moderate dimensions, attracted great attention. To turn this to account, a house of entertainment was erected and the place was turned into a pleasure resort known as the Cherry Garden.

There were tables and seats under the trees, and a bowling green and other means of diversion attached to the premises. It had seen its best days before the end of the seventeenth century.

On the borders of the Common, now the City Hall Park, was the Vineyard, which is said to have been a popular place of recreation and near the junction of what are now Greenwich and Warren Streets was the Bowling Green Garden, established there soon after the opening of the eighteenth century.

It was on a part of the Church Farm, quite out of town, for there were no streets then laid out above Crown, now Liberty Street, on the west side of the town and none above Frankfort on the east.

In 1735 the house of the Bowling Green Garden was occupied by John Miller, who was offering garden seeds of several sorts for sale. On March 29, 1738, it took fire and in a few minutes was completely consumed, Miller, who was then living in it, saving himself with difficulty.

A new house was erected and the place continued to attract visitors. There does not appear to have been any public road leading to it, but it was not a long walk or ride from the town and was finely situated on a hill near the river.

In November, 1759, when it was occupied by John Marshall, the militia company of grenadiers met here to celebrate the king’s birthday, when they roasted an ox and ate and drank loyally.

Marshall solicited the patronage of ladies and gentlemen and proposed to open his house for breakfasting every morning during the season. He describes it as “handsomely situated on the North River at the place known by the name of the Old Bowling Green but now called Mount Pleasant.” Some years later it became known as Vauxhall.

Bowling must have had some attraction for the people of New York, for in March, 1732-3, the corporation resolved to “lease a piece of land lying at the lower end of Broadway fronting the Fort to some of the inhabitants of the said Broadway in Order to be Inclosed to make a Bowling Green thereof, with Walks therein, for the Beauty & Ornament of the Said Street, as well as for the Recreation and Delight of the Inhabitants of this City.”

Bowling must have had some attraction for the people of New York, for in March, 1732-3, the corporation resolved to “lease a piece of land lying at the lower end of Broadway fronting the Fort to some of the inhabitants of the said Broadway in Order to be Inclosed to make a Bowling Green thereof, with Walks therein, for the Beauty & Ornament of the Said Street, as well as for the Recreation and Delight of the Inhabitants of this City.”

In October, 1734, it was accordingly leased to Frederick Phillipse, John Chambers and John Roosevelt for ten years, for a bowling-green only, at the yearly rental of one pepper-corn. In 1742 the lease was renewed for eleven years; to commence from the expiration of the first lease, at a rental of twenty shillings per annum.

In January, 1745, proposals were requested for laying it with turf and rendering it fit for bowling, which shows that it was then being used for that purpose. It was known as the New or Royal Bowling Green [now Bowling Green] and the one on the Church Farm as the Old Bowling Green.

This essay was drawn from Old Taverns of New York by William Harrison Bayles, published by Frank Allaben Genealogical Company, 42nd Street, New York, NY, in 1915. It was annotated by John Warren.

Illustrations, from above: A painting of the Bull’s Head Tavern on the Bowery in Manhattan, ca. 1783; Royal Cock Pit, London, 1808; Detail from Alvan Fisher’s “Eclipse with Race Track” (1823) courtesy Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute; Fresh Water Hill – labelled Freth Water – and the less settled portions of New York shown in a detail from Bernard Ratzer’s Plan of the city of New York, surveyed in 1767; the punch bowl awarded Lewis Morris, 1751 (Met Museum); Bull baiting advertisement from Old Taverns of New York; and the “Old Bowling Green” in King’s Farm, later known as the Church Farm, shown on James Lyne’s, “A plan of the city of New York,” 1729 (Norman B Leventhal Map & Education Center) – see a detailed version of the entire map here.

Source link