Profile of Leo Jacobs Real Estate Lawyer

Leo Jacobs is driven in his Bentley Flying Spur most days to his Plaza District law office — his chauffeur navigating the Grand Central Parkway from the stately home he recently bought in an old-money section of eastern Queens.

Not that long ago, the 37-year-old was an outer-borough attorney striving to make it in Manhattan out of a rented WeWork. Today he’s on the main stage, helping some of real estate’s biggest players as they try to protect their luxury homes and private jets from lenders, who, after years of distress, are taking a hard line with borrowers who can’t repay their loans.

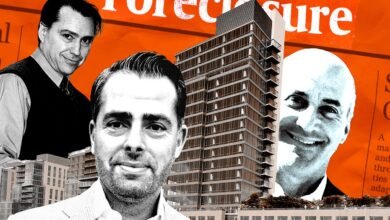

Jacobs is representing clients like the brothers Joe and Meyer Chetrit (sued at least a dozen times in the past two years), Joe Moinian (lost a hotel to his lender in June and is currently fighting at foreclosure cases on three large buildings) and Michael Stern (handed over control of Brooklyn’s tallest tower last year). That adds up. His company, Jacobs P.C., has advised on $5 billion worth of debt and equity restructuring, he claims.

“You might want to ask me, ‘Leo, you got all these clients. How did you get these billionaire clients?’” Jacobs said, demonstrating his habit for humble-bragging about the ultra-high net worths who come to him for help. “I have an answer for that.”

The key, he explained, is that he’s willing to take risks for his clients that establishment law firms won’t.

“Within ethical bounds completely,” he assures.

The high-profile attorney seems to be everywhere. He’s in the press when one of his notable clients gets sued. He’s a fixture on the industry speaking circuit and at networking events. He looks out from full-page ads in real estate publications with an all-business stare, stars in his firm’s melodramatic commercials and hosts his own podcast. He’s also gained a reputation for coming up with inventive strategies, even if his bravado can overshadow his clients’ issues.

“He’s the P. T. Barnum of bankruptcy and litigation because he’s a master marketer and showman,” said Greg Corbin, a broker who specializes in the clubby world of bankruptcy and restructuring where Jacobs has made his mark.

The fast rise has attracted its share of critics who say Jacobs’ big talk doesn’t match his results. His track record reveals a pattern of questionable tactics, sometimes pushing the boundary of what’s considered right or ethical.

But all of that might be the exact reason for his popularity.

“The same visibility and intensity that have drawn critics have also earned him a growing roster of clients,” Corbin said.

Negative one to zero

“I’m the last person you want to work with,” Jacobs tells the camera in the latest number in his marketing show, a master class geared at borrowers with problems. He pauses, then smiles. “You don’t want to work with me, and now all of a sudden you’ve gotta work with a guy like me.”

The rest plays out like an infomercial, but the sentiment isn’t hard to understand. Jacobs’ speciality is working with borrowers who have signed personal guarantees. When you default on a non-recourse loan, you can hand back the keys to the lender and go on about your business. But on a PG, the bank or debt fund can go after your personal assets to cover any losses.

Jacobs’ pitch to clients is that he’ll lift them “from negative one to zero.” He can’t get back the value their properties have lost, but he can help as they dig out of a hole.

“Leo’s team is relentless and creative and thinks outside the box compared to some of the legacy firms,” JDS Development’s Stern said. Jacobs worked with Stern on his personal guarantee at the Brooklyn Tower after the developer defaulted last year on a $240 million loan with Silverstein Properties.

Jacobs stumbled into this moment of success. He started out working with distressed clients not knowing that interest rates would climb and lead to one of the most agonizing periods for owners of commercial real estate since the Great Recession.

“You don’t want to work with me, and now all of a sudden you’ve gotta work with a guy like me.”

The most prominent example is Charles Cohen, who’s in a knock-down drag-out fight with his lender, Fortress Investment Group, over a $187 million personal guarantee. Fortress is now trying to get at a Greenwich mansion and a 220-foot megayacht it says Cohen is trying to shield from payment.

And it’s a similar story with multifamily syndicators Sean Kia and Ryan Andrade, whom several lenders are pursuing over their guarantees, including a $50 million-plus debt owed to Barry Sternlicht’s Starwood Property Trust.

A good lawyer can help reduce the scope of a guarantee, or at least give the borrower some leverage to negotiate a better deal. As a last line of defense (and oftentimes as a threat), they can oversee a bankruptcy.

Because Jacobs only represents borrowers, he can be more aggressive with lenders than some of his competitors, who work for both borrowers and lenders — or at large firms that do both.

“Some borrowers don’t like making a splash,” said Shlomo Chopp of Case Property Services, a company that helps restructure bad debts. “But for those borrowers looking for an attorney to come up with creative solutions, he may be the perfect guy.”

Going through motions

When Joe Moinian was about to lose his Hilton Garden Inn in Midtown, Jacobs deployed one of his inventive strategies.

On the eve of the UCC foreclosure auction in June, Jacobs filed a lawsuit asking the court to halt the auction because, he claimed, the lender had failed to include a piece of information in marketing materials advertising the sale. The missing detail was a $12 million personal-injury settlement at the property; its omission would invalidate the process.

Even without much of a dispute over whether a client has defaulted, Jacobs often finds a technical matter he can exploit to try and gum up the works.

This time, though, it didn’t land.

Attorneys for the lender foreclosing said they included detailed information about the settlement, and called Jacobs’ filing a “bad-faith, eleventh-hour effort” to try and stop the sale.

The judge in the case shot down his motion to stay the foreclosure, and Moinian lost the hotel at the auction the next day.

When his methods work, he pulls off a win.

In Queens, Jacobs is representing AB Capstone’s Meir Babaev, who is developing a 133-unit apartment building on the border of Ridgewood and Bushwick. When Babaev needed to get a forbearance on his $40 million loan, he signed a deed-in-lieu of foreclosure, which borrowers usually do when they agree to hand over the keys to their lenders.

But when Babaev’s lender moved to use the DIL to take over the property, Jacobs successfully argued that the agreement was merely a security and not an unconditional surrender. The judge overseeing the case granted Babaev a temporary restraining order in July.

The Chetrits turned to Jacobs for help after they defaulted on a $223 million loan with Richard Mack’s Mack Credit Strategies at the dilapidated Hotel Carter in Times Square. The attorney filed motions to get the case thrown out, arguing that Mack failed to include a key piece of paperwork — the pledge agreement — in his lawsuit.

That wasn’t his only angle. Jacobs is also trying to disqualify Mack’s attorney, Stephen Meister, claiming he represented the Chetrits in the past and has knowledge of confidential information about their business.

Meister “has represented Defendants for over two decades in transactions and during that representation, has obtained confidential information that is relevant to this action,” he wrote in court papers.

At a hearing in May, Meister got the opportunity to defend himself against his adversary’s claims, saying the effort to disqualify him was “a bad-faith and frivolous delay tactic” — a not-uncommon criticism of Jacobs’ tactics.

Meister acknowledged he represented Joe Chetrit in a case six years ago, about an Upper East Side townhouse he had rented. Meister said he dropped the case when Chetrit stopped paying him — and that was the end of their relationship.

“I never acquired any confidential information that’s remotely relevant to any of these cases,” he said. “This is a delay tactic and nothing more.”

At the hearing, the judge overseeing the case said that on first blush, she didn’t find Jacobs’ argument about the pledge agreement all that convincing but that she’d consider it further. The case is ongoing.

Jacobs’ name also pops up in a controversy with some of his biggest clients.

In July, a trio of life insurance companies sued Moinian, Meyer Chetrit and Edward Minskoff, claiming they defaulted on a $375 million loan backing an office building the three of them own together at 500-512 Seventh Avenue. (The Chetrit Organization has its office in the building.)

But the attorneys accuse the investors of impermissibly transferring more than $1 million of the building’s security deposits to various affiliates, saying the transfers smack of “intentional self-dealing, diversion and misappropriation” of the building’s cash.

Included in the list of dubious transactions was a $50,000 transfer to Jacobs’ law firm.

Jacobs told The Real Deal that the fee was for his retainer, and he was unaware of the source of the funds.

Queens kid

Jacobs reclines aloofly behind his desk at his new office, at 717 Fifth Avenue. He moved the firm there in January. The area commands some of the highest rents in the city — a big step up from the WeWork he used three years ago.

Behind him, where some other lawyer might hang contemporary art to signal cultural cachet, hangs a large framed picture of Batman at a piano.

“It’s the juxtaposition between aggression and elegance,” he explains.

As Jacobs talks about his background, he spins a heavy-sounding wedding band on his desk like a quarter.

“Tiffany ring,” he offers, unsolicited.

Compared to his more reserved contemporaries, Jacobs may come off as a bit coarse.

His conversation ends up in long, winding soliloquies in which he compares himself to Winston Churchill or a business psychiatrist (he has a bachelor’s degree in cognitive psychology from Queens College). At 6 foot 3 and 235 pounds, he’s got the build of a heavyweight boxer, and he leaves the top two buttons of his shirt undone to expose a hefty amount of heavage.

And he craves the spotlight, no matter how faint. Earlier this year he accepted an award for bankruptcy lawyer of the year at the Real Estate Development (RED) Awards — a questionable networking outfit known for handing out accolades like “best customer service elevator contractor of the year.”

But his résumé shows someone who started at the bottom of his profession and worked his way up.

The part of Queens Jacobs comes from is nicknamed “Queensistan” for the immigrants from Uzbekistan who arrived there after the fall of the Soviet Union.

They’re predominantly Bukharan Jews, a group from Central Asia whose famous members include billionaire diamond magnate Lev Leviev and Jacob Arabo, better known as Jacob the Jeweler.

Leo Jacobs’ real name is Ilevu Yakubov; he said he changed it about 12 years ago because people wouldn’t return his calls.

After college, he went to night classes at New York Law School and then got one of the most unglamorous jobs a new attorney could land: clearing violations with the Environmental Control Board.

“Knowing what the sidewalk measurements should be. That’s what administrative violations are,” he said.

But he was good at it and hustled his way into a job at a law firm on Wall Street where he built up a consumer affairs division. After two years, he took a job as corporate counsel with a family friend who was fixing and flipping Brooklyn multifamily properties that were underwater in the years following the 2008 financial crisis.

That’s where he learned about distress and stabilizing broken properties, and also about managing attorneys: Jacobs oversaw about 40 outside lawyers working with the company. After four years there, he started his own law firm.

There were very few people in his Bukharan community practicing contract law, he discovered. This gave him an edge.

“I didn’t know it at the time, but the majority of the people that practice law in my community are effectively personal injury attorneys,” he said. “So I was a fucking unicorn.”

Jacobs had partners at his firm but there was a disagreement over the company’s direction: They wanted to go to Long Island while he had ambitions of Manhattan. They went their separate ways, but Jacobs didn’t have money to make his move, so he took a shot on a WeWork near Grand Central.

“I was like, ‘Fuck it, if it doesn’t work out it doesn’t work out. What’s the worst that can happen? I’ll go back to Queens.’”

His big Manhattan break came when he helped a well-known restaurateur from his community out of a jam during the pandemic.

After missing his March 2020 rent payment, Ilya Zavolunov, owner of ZAVŌ Restaurant & Lounge on East 58th Street, got sued by his landlord, Olshan Properties, on his personal guarantee. But the city had just put a new law on the books that business owners weren’t personally liable if they defaulted on their leases during the first six months of the Covid outbreak.

Jacobs argued successfully in court that Olshan didn’t send the notice to cure in time to meet the law’s retroactive deadline. The case helped raise his profile, and he picked up bigger and bigger clients.

But some of his clients are people that other, more established attorneys won’t work with — often because they have a reputation for not paying their bills, Jacobs’ critics say. Joe Chetrit, for one, is currently being sued for allegedly not paying back a $3 million loan he took out to pay a portion of a legal settlement.

He’s aware of how he comes off but doesn’t much care.

“I’ve had my fair share of people say, he talks a lot or he doesn’t know what he’s talking about, but it always shows up in the result,” he said.

Hiring well-respected veterans Robert Sasloff and Wayne Greenwald has helped with the company’s stature. And its growth has paid off for its founder: Jacobs last year bought a Tudor-style home in Jamaica Estates — the tony neighborhood in Queens where Donald Trump lived as a child.

Getting in (or out of) line

Jacobs’ aggressive tactics sometimes walk the line of what’s permissible.

One example: In 2022 he represented an office manager at a Westchester dental office who claimed she was fired in retaliation after raising concerns about Medicaid fraud.

But at a deposition, his client admitted that she fabricated the claims.

Falsely accusing a doctor of Medicaid fraud is akin to throwing a nuclear bomb, said the dentists’ attorneys, who accused Jacobs of failing to reasonably investigate his client’s allegations before filing multiple claims. What’s more, they said, Jacobs abused the discovery process by making extensive records requests that the judge determined were part of an overly broad fishing expedition.

Jacobs knew his client’s claims were false, the lawyers said, yet pushed forward with litigation anyway.

“It is clear that the strategy was to force Defendants to litigate so they incur staggering litigation fees and smear their professional reputations as a means to pressure them to settle the claims,” the lawyers wrote.

They asked the judge to impose sanctions large enough to deter future misconduct, citing one case where an attorney was fined $20,000 for making frivolous arguments.

Four months later, Jacobs and his client settled the case, in part citing “a pending motion for sanctions.”

In another case, opposing attorneys asked a judge to sanction Jacobs for using delay tactics to stall a UCC foreclosure.

He had been representing a Brooklyn investor named Ahron Rudich who was set to lose his interests in a New Jersey condo project after defaulting on more than $4 million in loans.

Rudich was scheduled to turn over his shares in the project to the local sheriff in March 2024 when Jacobs notified the court he was stepping down from the case, explaining he had a disagreement with his client concerning fees. Jacobs and Rudich didn’t show up on the day he was scheduled to turn over the shares.

Then, a few days before the auction, Jacobs filed a petition asking the court for an order to stay the sale, explaining his client was on the verge of getting a bridge loan to repay his debt. Jacobs said the loan was expected to close by April 30, 2024. But the day after the filing, one of his attorneys told the opposing lawyers he didn’t expect the deal to close on time, due to Passover.

Jonathan Borg, attorney for the lender, had warned Jacobs that his team would consider any motion frivolous, because Jacobs hadn’t filed proper paperwork saying he was working with Rudich again. His timely resignation notice and failure to show up on the turnover date “reek of the improper (procedural) stench of a delay,” Borg and his team added.

“I ask this in all seriousness, what kind of games are you playing here?” Borg wrote in an email to Jacobs. “I find your conduct here to be frivolous and unethical, at best.”

Borg asked the court to award $4,740 in damages and $10,000 in attorneys’ fees.

Jacobs told Borg in an email that the matter with his client was a legitimate dispute that got resolved (“He didn’t pay. We came off. He paid again. We came on.”) and in court papers denied that his filing was frivolous.

“Some call my approach aggressive; I call it decisive,” he said, maintaining that he is “always within the four corners of the law.” Fast legal action can save buildings, and fortunes, he added.

Jacobs was perhaps clearest about his approach on an episode of his podcast, speaking with his partner Adam Sherman.

“And we’re not scared of sanctions, are we Adam?,” Jacobs interjected.

“No, as you say, get in line,” Sherman answered, fearless.

“Get in fucking line, that’s right!”

Billable hours

Ultimately, Jacobs did resign from the Rudich case in January, once again citing a breakdown in the relationship with his client over fees. It was one of three cases this year when he did so.

In all three, Jacobs told the court that there was a “complete breakdown in the attorney-client relationship between the Petitioners and Jacobs P.C., regarding the issues of fees and other professional considerations that require that Jacobs P.C. be permitted to withdraw as counsel of record in this action.”

In March, Jacobs was working on one of these cases, trying to prevent a short sale of a property in New York’s Orange County. Jacobs argued the owner had a deal to sell the property at a price that would produce a profit, so the foreclosure auction should be postponed. He resigned from the case after about two months.

But an investor who stepped in to try and save the property, Shabsi Pfeiffer, said Jacobs didn’t give him the attention he thought he deserved. Jacobs charged too much for the work he did, he added.

“Leo should rather be having a law firm somewhere in Brooklyn, maybe charging $400 an hour,” he said.

It’s not just former clients with an axe to grind that have highlighted a fee problem.

In a federal bankruptcy case in early 2022, Jacobs was forced to pay back a fee after the trustee in the case filed and won a motion to have his fees disgorged, saying they were too high.

“Here, Counsel received $30,000 to prosecute the Debtor’s no-asset Chapter 7 case, which is over 10 times the average amount of fees charged by practitioners for similar cases in this district,” the trustee wrote in court papers.

In response, Jacobs said he had made an error in his paperwork — one of several mistakes he acknowledged making — and that the $30,000 was inclusive of all the work he did on the case, including an out-of-court restructuring designed to prevent filing for bankruptcy.

“I appreciate the trustee taking my firm to task,” he wrote. “However, we did perform the agreed to and required services. We are entitled to compensation for those services.”

Jacobs ultimately reached a settlement to hand over $25,000 to the trustee.

Jacobs told TRD that he can charge “exorbitant rates,” albeit within the bounds of ethics.

“There’s a premium to restructuring advice, particularly if there are two or three or four complex issues,” he said. “Frankly, there’s not a lot of other people who can do this kind of work.”

888-LEO’S-LAW

The current distress in commercial real estate has opened a lane for newcomers like Jacobs to build businesses.

That’s not to say he’s forging a new path. The widely recognized market leader in bankruptcy law is Kevin Nash of Goldberg Weprin.

Nash, who has been practicing for 40 years, said he thinks of Jacobs mostly for litigating in the state courts, but that dealing with the sophistication and intricacies of the federal bankruptcy courts is another matter.

“People litigate all the time in New York,” he said. “You can’t just walk into bankruptcy court and say you’re a bankruptcy lawyer. It takes a lot of time.”

When asked what he thought of Nash’s assessment, Jacobs gave the diplomatic answer.

“You want my response? Kevin Nash is a competent bankruptcy professional,” he said curtly.

Lawyers in New York don’t always mix; they’re specialized into little clans, like the characters in Tom Wolfe’s “Bonfire of the Vanities.”

Wolfe’s protagonist, Wall Street bond trader Sherman McCoy, is a suspect in a late-night hit-and-run who turns to his family’s white-shoe attorney Freddy Button for advice.

Button says McCoy should avoid hiring a well-mannered uptown attorney for this case but instead pick one of those criminal attorneys who works down on Lower Broadway.

“They’re the absolute bottom of the barrel of the legal profession,” Button says. “They’re crude, coarse, sleazy, unappetizing — you can’t even imagine what they’re like. But that’s who I’d go to. … In certain cases you’ve got to use them.”

Some of Leo Jacobs’ clients might have overheard. There’s a big difference between the Big Law attorneys who advise New York’s CRE players on billion-dollar transactions and the ones who get the call when a borrower needs a street brawler to fight about foreclosures.

The more baldly ambitious ones embrace their place in the hierarchy and roll with it.

Like Cellino & Barnes, with their iconic jingle. Or Seth Harris, the blue-hued personal injury attorney whose subway ads read: “I’m down with NYC. Yeah, you know me.”

If you want Harris, you call 800-PAIN-LAW. With Jacobs, you might listen to his podcast, “Confronting the Impossible,” or take his master class. And then if you’re the right kind of client at the worst kind of moment, you call Leo.