Poems, Books & Bullets: The Seeger Family & World War One

Musicologist and composer Charles Louis Seeger Jr., a pacifist and conscientious objector, was the father of folk singers Pete Seeger, Mike Seeger and Peggy Seeger all of whom were associated with anti-war movements later in the twentieth century. His younger brother Alan Seeger was a Greenwich Village poet and bohemian who had settled in Paris in 1912.

Musicologist and composer Charles Louis Seeger Jr., a pacifist and conscientious objector, was the father of folk singers Pete Seeger, Mike Seeger and Peggy Seeger all of whom were associated with anti-war movements later in the twentieth century. His younger brother Alan Seeger was a Greenwich Village poet and bohemian who had settled in Paris in 1912.

When Germany declared war on France he joined the French Foreign Legion and was killed in 1916 in action at the Battle of the Somme. His writings were published posthumously and would cement his reputation as an American war poet. In France, his memory is revered to this day.

A Bohemian Spirit

Alan Seeger was born on June 22, 1888, in the city of New York into a family that traced their German-American heritage to the eighteenth century when Karl Ludwig Seeger, a physician from Württemberg, moved to the United States after the American Revolution and married into the New England Puritan lineage of Joseph and Mary Parsons during the 1780s.

Alan’s parents upheld Unitarian beliefs of freedom, individual responsibility and religious diversity. He was educated at the Horace Mann School in Greenwich Village (then connected to Columbia University). Charles Seeger Sr. was an influential figure in international commerce and maintained close business ties with Mexico City (where he had been born to American parents).

Living on Staten Island, Alan’s younger days were spent in carefree and privileged surroundings. In 1900, the family settled in Mexico City for two years and memories of the period reoccur in a number of his later

Living on Staten Island, Alan’s younger days were spent in carefree and privileged surroundings. In 1900, the family settled in Mexico City for two years and memories of the period reoccur in a number of his later

writings, particularly in his longest poem “The Deserted Garden.”

In 1902, Alan and his brother returned to New York City to be further educated at Hackley School in Tarrytown (founded in 1899 as a Unitarian alternative to Episcopal boarding schools). He then attended Harvard College where fellow students in the Class of 1910 included the poets T. S. Eliot and John Reed, as well as the future Pulitzer Prize winning political author Walter Lippmann.

He became co-editor of the in-house Harvard Monthly magazine and started writing poetry whilst testing his talent by translating passages from Dante Alighieri, Ludovico Ariosto and other classical greats.

Following graduation with a BA in 1910, he took up residence in a boarding house at 61 Washington Square. Without an urgent need to take up paid employment, he spent his time writing poetry and embraced the bohemian atmosphere of Greenwich Village. His residence was run by a Swiss immigrant named Madame Catherine Branchard. Throughout her tenure lasting from 1886 until her death in 1937, she let her rooms to writers and artists only.

An alphabet of creative individuals entered her residence at one time or another, including Willa Cather, Stephen Crane, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Robert Moses, Frank Norris, Sydney Porter, John Reed, Arnold Rönnebeck and other figures that would feature prominently in American art and literature. The residence was dubbed “The House of Genius.” The building was torn down in 1948 following a preservation battle. Real estate has neither conscience nor memory.

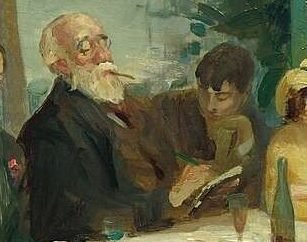

Seeger enjoyed the Frenchness of Petitpas Restaurant at 317 West 29th Street where frequent soirées were held for the benefit of the artistic fraternity in which the painter John Butler Yeats, father of the Irish poet W. B. Yeats, played a leading role.

One such scene has been preserved by John Sloan in his painting “Yeats at Petitpas” (ca. 1910/2). Under the watchful eye of Célestine Petitpas herself, it depicts a round table of poets and artists that includes Alan Seeger seated next to Yeats – a final memory of Seeger on American soil.

One such scene has been preserved by John Sloan in his painting “Yeats at Petitpas” (ca. 1910/2). Under the watchful eye of Célestine Petitpas herself, it depicts a round table of poets and artists that includes Alan Seeger seated next to Yeats – a final memory of Seeger on American soil.

Young American talent was being pulled in numbers to Paris and Alan also fell for the appeal. After a period of writing poetry in Greenwich Village and doing some journalistic work, he packed his bags in 1912 and crossed the Atlantic.

Foreign Legion

Seeger settled on the Left Bank among a set of American expatriates continuing the bohemian life style he had enjoyed in the Village. During that period he composed a collection of poems that he called Juvenilia. In the early summer of 1914, he visited London to discuss its possible publication.Events intervened.

When Germany declared war on France on August 3, 1914, Seeger was living on the Rue du Sommerard in the lively Sorbonne student quarter with plenty of small booksellers in the neighborhood. Eleven days later he joined up as a private in the Foreign Legion (the French Army prohibited enlistment by foreigners – except in “La Légion”). He took the step, as he wrote at the time, not out of hatred against Germany, but “purely out of love for France.”

The Foreign Legion was an odd choice for those who were driven by idealism. It had a fierce but dark reputation of being a force that consisted in part of the dregs of Europe and beyond. Many legionnaires had escaped the law or run away from nefarious events in their past. Dropouts, outcasts and criminals fought alongside hardened veterans of colonial battles in Algeria and Morocco. For many of them signing up to the “suicide squad” was their last chance.

Approximately one hundred American volunteers joined the Foreign Legion and for many it was suicide indeed. Nearly all had been wounded (more than once) and many of them lost their lives. It was the only military unit in which Americans of different races were comrades in arms. All volunteers were decorated by the French government in the aftermath of combat.

After basic training at Rouen, Seeger’s regiment was sent to the trenches of northern France where, to his dismay (as he reported to the New York Sun in December 1914), he saw little action and spent long hours of boredom stuck in “a hole” under fire of batteries from a distant enemy. That changed in September 1915 when the Allies launched an offensive in the Champagne region, but failed to force a breakthrough.

In October he was mistakenly reported killed in action. His regiment spent much of the following months on reserve. A bout of bronchitis kept him out of service for some time, but he continued to write poetry.

During the two years in the Foreign Legion, Seeger wrote regular dispatches to the New York Sun and contributed the essay “As a Soldier Thinks of War” for Walter Lippman’s magazine The New Republic. Although deeply opposed to war, the latter judged that it was necessary to side with the Allies.

For Seeger, the fight was an imperative. In his poem “A Message to America,” he spoke out against his country’s “moral” failure to join the war. America would not enter until April 1917 and its forces were not engaged in combat until more than a year later.

As the war progressed, the theme of death grew stronger in his poetry. On June 21, 1916, he sent a brief letter from the Western Front to his “war godmother.” Amongst American Legionnaires it was a common practice to seek out a “marraine de guerre” (a female confidante) for support. Alan’s letter, consisting of nine sentences, was written in short and bullet-like phrases. The update was accompanied by a twenty-four line poem that consisted of three stanzas (6+8+10 lines).

Seeger had penned this, his most famous poem “I Have a Rendezvous with Death,” while stationed during the winter at the small town of Crèvecoeur in the Oise department of Northern France. The town’s name translates to “heartbreak.” Serving as backdrop to the poem, the name fits its grim content about an imminent fateful encounter between the narrator and Death personified.

Seeger had penned this, his most famous poem “I Have a Rendezvous with Death,” while stationed during the winter at the small town of Crèvecoeur in the Oise department of Northern France. The town’s name translates to “heartbreak.” Serving as backdrop to the poem, the name fits its grim content about an imminent fateful encounter between the narrator and Death personified.

On July 4, 1916, three days after the start of a renewed offensive, Alan Seeger died during the massive Allied attack at the Somme River, being hit by a barrage of German machine gunfire during his unit’s assault on the village of Belloy-en-Santerre. He was buried in a mass grave.

A collection of Seeger’s poetry was published in New York City by Charles Scribner’s Sons in December that year with a sympathetic introduction by the Scottish critic and author William Archer. Simply called Poems, the book initially reached a smallish audience.

Bullets & Books

In 1917, librarian and literary scholar Theodore Wesley Koch was posted in London representing the Library of Congress. There he took an interest in British efforts to supply books to serving soldiers. He produced a detailed report on Books in Camp, Trench and Hospital, investigating first-hand what soldiers were reading.

As well as novels, he noted that anthologies of poetry were in demand, in addition to books on arts, crafts, hobbies and the like. There was one crucial condition: size mattered and books had to be portable.

Prolonged spells of inaction in the trenches made reading a vital pastime for soldiers and a means of escaping from the unfolding tragedy around them. Book supply to prisoners-of-war was equally vital. In the camps internees organized education and training groups.

Professionals, artists and academics became teachers to fellow captives; the camp a “university” behind barbed wire. By the time Koch returned home, the United States had entered the war he was asked to use his expertise on behalf of the “Library War Service.”

Founded in 1876, the American Library Association (ALA) was designated by the government to administer library services to the troops, both at home and abroad. Navy ships carried small libraries as cargo and more than a million books were distributed by the Library War Service in Paris under the administration of Ohio-born author Burton Egbert Stevenson.

Founded in 1876, the American Library Association (ALA) was designated by the government to administer library services to the troops, both at home and abroad. Navy ships carried small libraries as cargo and more than a million books were distributed by the Library War Service in Paris under the administration of Ohio-born author Burton Egbert Stevenson.

In its request for contributions, the ALA avoided intervention or censorship where possible. Its motto was “Give every man the book he needs when he wants it.” The flow of books also assisted in the formation of a reference library on topics such as aviation, mechanics or military science, helping soldiers prepare for future civilian life.

With the departure of American troops after the war, the need for the service became unclear. In 1920 the ALA pushed ahead with the foundation of an “American Library.” Using the collection of wartime books as its core, the Library’s charter promised to bring the best of literary America to French readers.

It found a palatial home at 10 Rue de l’Elysée, overlooking the gardens of the Elysée Palace. The Library’s motto reflected the spirit of its creation: “Atrum post bellum, ex libris lux” (After the Darkness of War, the Light of Books). Burton Stevenson oversaw the transition.

Among the first trustees of the Library was the expatriate novelist Edith Wharton. Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein were amongst its early patrons. The Library was still used by lingering soldiers and expatriates who had remained in Paris, but was also opened to civilians and used increasingly by French citizens as well. But its financial survival was not guaranteed.

Charles and Elsie Seeger set out to create a lasting memory of their son’s sacrifice in the fight against tyranny. By late 1916, they resided in Paris with Charles working in a senior position for the India Rubber Products Company.

With Scribner publishers in New York City, he had conceived the publication of Poems, followed by his son’s Diary and Letters, and promoted the sale of these publications. An account was set up in Paris to bank the royalties.

Seeger then approached the American Library Fund offering a substantial endowment in his son’s name. It was agreed that all interest earned on the “Alan Seeger Endowment,” would be used for expanding the collection into literature and poetry. The Library’s future was secured and Charles became its first board chairman.

Seeger then approached the American Library Fund offering a substantial endowment in his son’s name. It was agreed that all interest earned on the “Alan Seeger Endowment,” would be used for expanding the collection into literature and poetry. The Library’s future was secured and Charles became its first board chairman.

Post-war France was intrigued by American music and literature. Bookstores saw increasing displays of American classics in both languages, but soaring exchange rates had made imported books prohibitively expensive. The American Library became a vital resource to a new generation of French readers and intellectuals, giving cultural depth to the post-war relationship between the United States and France.

French Tribute

On July 4, 1923, French Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré dedicated a monument in the Place des États-Unis to the American soldiers who had volunteered to fight on the nation’s behalf. Financed through a public subscription, the statue was executed by Jean Boucher, himself a veteran of the Battle of Verdun. As a Professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, he enjoyed a reputation for public memorial sculptures to soldiers who had died for France and his native Brittany.

The bronze soldier on a plinth was inspired by Alan Seeger for which Boucher had used a photograph of the young New Yorker. His name is mentioned among those of twenty-three other Americans who had fallen in the ranks of the Foreign Legion on the back of the plinth.

On either side of the base of the statue, are two excerpts from Seeger’s “Ode in Memory of the American Volunteers Fallen for France,” a poem created shortly before his death.

Over time, Seeger’s “I Have a Rendezvous with Death” became recognized as a classic in the treasury of war poetry, a staple of memorial services and part of the high-school English curriculum. It was President John Kennedy’s favorite poem. Seeger has been called the “American Rupert Brooke,” the English soldier-poet who had died in combat too.

Over time, Seeger’s “I Have a Rendezvous with Death” became recognized as a classic in the treasury of war poetry, a staple of memorial services and part of the high-school English curriculum. It was President John Kennedy’s favorite poem. Seeger has been called the “American Rupert Brooke,” the English soldier-poet who had died in combat too.

The poem continues to resonate with French readers. In the 1970s the city of Biarritz honored the poet’s name with the creation of an “Avenue Alan Seeger” and he was quoted by President Emmanuel Macron in April 2018 in a speech to Congress evoking the joined battles the two nations had fought for democracy, whilst warning of freedom’s fragility.

On the centenary of the American Library in 2020, Pete Seeger recorded a reading of his uncle’s poem as a personal gift to the institution. It felt like a symbolic reconciliation between the pacifist and the soldier who, each in their own manner, had defended the same fundamental principle – the dignity of living life in freedom.

Illustrations, from above: John Butler Yeats and Alan Seeger detail from John Sloan’s “Yeats at Petitpas,” ca 1910-12 (National Gallery of Art); Alan Seeger at Harvard, 1910; Sloan’s “Yeats at Petitpas” showing, from left to right around the table, literary critic Van Wyck Brooks; painter John Butler Yeats; poet Alan Seeger; the artist’s wife, Dolly Sloan; Célestine Petitpas (standing); fiction writer Robert Sneddon; miniature painter Eulabee Dix; John Sloan, the artist (corner); Fred King, the editor of Literary Digest; and, in the foreground, Vera Jelihovsky Johnston, wife of the Irish scholar Charles Johnston; the ruins of Belloy-en-Santerre after the World War One Battle of the Somme where Alan Seeger died in action; a Library War Service poster by Charles Buckles Falls, 1917; a bookplate of the American Library in Paris, founded in 1920; and The Monument to the American Volunteers Fallen for France at the Place des États-Unis, topped by a statue in the likeness of poet Alan Seeger.

Source link