One Of Sullivan County’s Most Destructive Fires

Brush fires have been much in the news of late, and those familiar with Sullivan County history have been moved to recall massively destructive wildfires from years gone by, including the May, 1884 blaze that wiped out thousands of acres, including most of the hamlet of Gilman’s in the town of Forestburgh.

Brush fires have been much in the news of late, and those familiar with Sullivan County history have been moved to recall massively destructive wildfires from years gone by, including the May, 1884 blaze that wiped out thousands of acres, including most of the hamlet of Gilman’s in the town of Forestburgh.

Gilman’s was not a large community, and the damage to buildings and infrastructure was far less than that of other historic fires, such as the August, 1909 Monticello blaze or the June, 1913 fire in Liberty, but the devastation caused by its spread to the natural surroundings is what sets it apart from all the others.

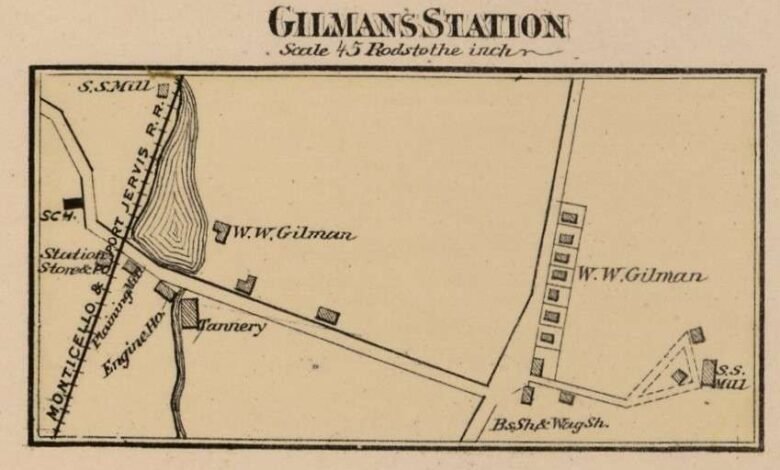

The community had grown up around the tannery of Winthrop Watson Gilman, a member of one of the wealthiest families in the country, who had come to Sullivan County in the 1840s, just as the leather tanning industry was beginning to burgeon here.

Within a few years, Gilman was operating a thriving lumber business in addition to the tannery, and had constructed some 32 buildings in a small community bearing his name, anchored by a steam-powered gang sawmill comprising 22 saws that turned out three to four million board feet of lumber a year, all of it shipped to the city of New York.

When the Port Jervis & Monticello Railroad came through the area in 1871, Gilman’s became known as Gilman’s Depot, or Gilman’s Station, and the railroad station was built onto the sawmill so that lumber could be loaded directly onto the trains. The community also included a schoolhouse, a company store, a post office and a boarding house.

In May of 1884, fire broke out one afternoon about a mile from the railroad depot and burned out of control for days. It was the second major blaze to strike the hamlet in two years, and by far the worst. Although no one seems to know for certain, it is generally believed that the fire was started by a spark from the wood-burning engine of a train.

“The wind was blowing a gale,” the New York Times reported. “The men from Gilman’s sawmill fought the fire, but without avail. The residents were obliged to flee for their lives, and were unable to save anything and not more than half a dozen houses are standing within a radius of five miles. The fire is still burning to the east and south of Gilman’s. The extensive tannery and sawmills of W. W. Gilman have been destroyed. The whole settlement is owned by him and he is unable to estimate his loss. Two

railroad bridges have also been burned.”

Later reports estimated the hamlet itself suffered more than $120,000 in property loss. That is more than $3 million in today’s dollars. The damage to the surrounding wilderness was incalculable.

The devastation to the thousands of acres of woodlands was so complete, when Henry George and his colleagues Louis F. Post and William Croasdale purchased 2,000 acres a few years later for the erection of Merriewold Park, one observer described the land as “looking rather like plum pudding with the cloves sticking out.” And the poor condition of the adjacent land was also instrumental in prompting Chester W. Chapin to purchase large tracts in the 1890s in an attempt to restore it.

To make matters worse, W.W. Gilman had refused to pay for insurance on any of his buildings, and had to absorb the entire loss himself. Despite that fact, he was uncharacteristically philosophical.

“If I had had policies on this property during the past 40 years the insurance companies would have been paid its entire value,” he mused afterwards. “I saved that much money and had the use of it.”

According to the Republican Watchman newspaper, Gilman had the tannery operation up and running again less than a month after the fire had been brought under control.

“With their indominable pluck, the Messrs. Gilman put up news buildings and purchased new machinery, and in less than four weeks after the fire a new tannery was in full operation, and has been running successfully ever since, turning out many thousand sides of sole leather every month, giving employment to over forty men, and taking a front rank in the tanning interests of this state,” the Watchman reported in its August 21, 1885 edition.

W. W. Gilman contracted pneumonia in late November of 1885 and died on December 5. He was 78. Although no one was quite sure exactly how much he was worth, in a notice of Gilman’s death, the New York Times put the value of his holdings at between two and three million dollars.

Illustration: A map of Gilman’s Station, circa 1872.

Source link