New York’s Enlightenment Legacy: Science and Social Mobility

The French Revolution abolished the privileges that were traditionally reserved to noblemen. Military careers were opened to all talent instead.

The French Revolution abolished the privileges that were traditionally reserved to noblemen. Military careers were opened to all talent instead.

In the wars following the Revolution, masses of young males were drawn into the armed forces, fighting feudalism. It was in this environment that Napoleon developed his thinking on military strategy.

The École Polytechnique was established in 1794, five years after the toppling of Louis XVI from the throne. A decade later, Napoleon granted the institution military status with the motto: “Pour la Patrie, les Sciences et la Gloire” (For the Nation, for Science and for Glory).

His aim was to create a professional center for training civil and military engineers. The institution set a standard for all later technical schools, including two iconic New York institutions.

École Polytechnique & West Point

The school was a product of Enlightenment ideals (which emphasized reason, individualism, skepticism, and individual rights and liberties) stipulating that educators should focus on the sciences. The teaching of mathematics superseded the attention to Greek and Latin authors.

Scientists took on a prominent role in society, their influence was felt everywhere. The École Polytechnique trained some of the nineteenth century’s greatest mathematical and scientific minds.

While the school focused on training French engineers and officials, it soon (starting as early as 1798) admitted students from abroad. American educators visiting the École brought back ideas about curriculum design and teaching methods that they had encountered in Paris.

While the school focused on training French engineers and officials, it soon (starting as early as 1798) admitted students from abroad. American educators visiting the École brought back ideas about curriculum design and teaching methods that they had encountered in Paris.

The school’s scientific and mathematical model combined with practical applications, influenced the establishment of similar colleges in the United States.

Located on a plateau on the west bank of the Hudson River, West Point played a major role during the American Revolution. General George Washington considered it a crucial strategic spot and in 1778 he commissioned Thaddeus Kosciuszko, a Polish military architect and Colonel in the Continental Army, to design fortifications for West Point.

A year later he transferred his headquarters there. Fortress West Point was never captured by the British.

In the 1790s, President Washington stressed the necessity of establishing an institution to train officers and engineers, but Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson objected to the concept of a professional army, warning that colonists would not accept the “oppression” of military conscription.

During his presidency Jefferson changed his mind: in March 1802 he signed legislation that founded the United States Military Academy (USMA) which fell under the auspices of the Corps of Engineers.

Sylvanus Thayer (1785-1872) was a graduate from West Point in 1808 with a keen interest in engineering. He quickly rose through the ranks, serving with distinction in the War of 1812.

Sylvanus Thayer (1785-1872) was a graduate from West Point in 1808 with a keen interest in engineering. He quickly rose through the ranks, serving with distinction in the War of 1812.

Three years later he traveled to Paris and studied for two years at the École Polytechnique. From 1817 to 1833 he acted as Superintendent of West Point, making engineering its core orientation.

For his transformative role in its development he is often referred to as the “Father of West Point.”

He made another decisive intervention. A graduate of the École Polytechnique, Claudius Crozet (1789-1864) had served as Captain of Engineers during the battles of Borodino and Waterloo.

After Napoleon’s defeat and the ensuing occupation of Paris by enemy troops he, like many fellow officers, resigned his commission (others were sacked or imprisoned). Some of them were recruited by American agents. Crozet was one of them.

Once made Superintendent at West Point in 1817, Sylvanus Thayer appointed him as Professor of Engineering. Crozet participated in overhauling the school’s methods of instruction on the model of the École Polytechnique.

Paris remained an attraction to aspiring engineers. Benjamin Franklin’s great-grandson Alexander Dallas Bache studied at the École in the 1820s. He would become a prominent figure in American technical education, serving as President of the National Academy of Sciences.

William Henry Chase (1798-1870) studied at the school in the early 1830s. He later became a Professor at West Point and played a role in shaping its curriculum.

William Henry Chase (1798-1870) studied at the school in the early 1830s. He later became a Professor at West Point and played a role in shaping its curriculum.

Both institutions participated in engineering projects that, to this day, remain of vital political consequence (and tension).

The Parisian school was deeply involved in the construction of the Suez Canal; West Point graduates were associated with the planning and completion of the Panama Canal. There is a symbolical link as well.

The “École Polytechnique Monument” is a sculpture by Corneille Henri Teunissen. Placed in the school’s courtyard, it commemorates the cadets who died defending Paris against the invasion of the coalition in 1814.

In 1919, honoring the American participation in the First World War, the school presented a full-size casting of the statue to West Point as a token of the historical association between the two nations and institutions.

Industrialist, Inventor & Idealist

Although the Parisian academy was praised for its legacy in engineering, it also made a socio-political impact which manifested itself in the career of Pierre Leroux. Born in 1797, the latter attended the École Polytechnique before starting a career as a typographer.

In 1824, he founded Le Globe newspaper which, in 1832, was the first French periodical to introduce the term “socialism” to its readers. One of the main aims of the movement was to combat ignorance.

Pierre Leroux, using print as his medium, spread ideas of democracy, liberation and social justice. Socialism was born with a printers’ tag around its neck.

This social commitment inspired an American engineer. Born in 1791 in the city of New York, Peter Cooper grew up in Peekskill on the Hudson River in northwestern Westchester County.

His father went through a string of jobs, but failed to make a proper living. From an early age, Peter had to help out. As a consequence he received little formal education, a lack of schooling he would regret throughout his life.

Apprenticed to a carriage maker, Cooper proved to be a resourceful and inventive worker. Once he set out on his own, he became one of Manhattan’s outstanding inventors and industrialists.

In 1830, Cooper designed one of America’s first steam-powered locomotives (named Tom Thumb); in 1845, he patented a “condensed” gelatin food product that later became the “Jell-O” fruit dessert; in 1852, his Trenton Iron Company designed a new type of structural beam that could be used in large-scale construction projects which found its way into the New York’s Assay Offices, the Mint in Philadelphia and the Capitol dome in Washington; in 1858 he participated in the creation of the first transatlantic telegraph line. Cooper was one of the engineers that shaped the modern world.

In 1830, Cooper designed one of America’s first steam-powered locomotives (named Tom Thumb); in 1845, he patented a “condensed” gelatin food product that later became the “Jell-O” fruit dessert; in 1852, his Trenton Iron Company designed a new type of structural beam that could be used in large-scale construction projects which found its way into the New York’s Assay Offices, the Mint in Philadelphia and the Capitol dome in Washington; in 1858 he participated in the creation of the first transatlantic telegraph line. Cooper was one of the engineers that shaped the modern world.

In the early 1830s, Cooper met up with an (unidentified) friend by the name of “Dr. Rogers” who had just returned from a visit to the École Polytechnique. What moved him in their conversation was the image of impoverished students who pursued their coursework with total dedication and stubborn persistence.

Remembering his own struggle to fill the gap in education, he became committed to the idea of founding a similar institution in the midst of Manhattan’s immigrant community.

Cooper was a hard line Protestant, but his vision of education was one of diversity. Religious doctrine should not interfere with teaching. Cooper’s ambition was to create a non-sectarian model of education that was free of charge.

He was convinced that there were any number of potential engineers and inventors among Manhattan’s workers who would grasp the opportunity to enjoy the “beauties and benefits” of scientific instruction.

He wanted graduates to acquire technical mastery and entrepreneurial skills, perfect their linguistic means of interaction, enrich minds, spark creativity and instill a sense of social justice.

The “Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art” first opened its doors in 1859. Located at Astor Place in Manhattan’s East Village, the Union was the first fireproof building in New York constructed with iron beams (manufactured by Cooper).

It also contained a lift shaft, installed before the introduction of commercial elevators. The circular shaft was later fitted with an elevator by Elisha Otis. The Cooper Union building became a proud landmark in downtown Manhattan.

The Great Hall occupied the basement level and soon became an important venue for political addresses. Abraham Lincoln gave a speech there early in 1860 which helped propelled him into contention for the Republican nomination that year.

For visitors such as the future Edward VII, an inspection of Cooper Union was a must. As the years went by, guest speakers from Mark Twain and Woodrow Wilson to Bertrand Russell were welcomed at the Union.

Following Cooper’s death in 1883, Dublin-born Augustus Saint-Gaudens, New York’s pre-eminent sculptor at the time and one of the earliest alumni of Cooper Union (class of 1864), was commissioned to design a monument in his honor.

He collaborated with the architect Stanford White who created the piece’s marble and granite canopy. The official dedication took place on May 29, 1897 at the northern end of Cooper Park.

The Cooper Union represented the realization of an idea that had occupied its founder for nearly thirty years: providing a tuition-free education to men and women of all social, ethnic and religious backgrounds.

More than 2,000 people applied to take classes, many of which were offered in the evening. The Union’s reading room was open to the public and, unlike New York City’s other libraries, functioned during the evening for the benefit of working people.

Immigrants flocked both day and night to the Union for courses in mechanics and mathematics. Young women jammed the school of design.

The Union’s library was the favorite haunt of an immigrant boy named Felix Frankfurter who would become one of the nation’s great jurists.

Among its early alumni was Thomas Edison. The impoverished inventor could never have afforded the tuition at a regular engineering school. The list of successful careers associated with the school is considerable.

The career of Mihajlo Pupin (known as Michael Pupin) highlights the vital supporting role of the Union and similar institutions.

Born in October 1858 in the Serbian village of Idvor (then in Austria-Hungary), both Pupin’s parents were illiterate. As a boy he worked in the fields tending sheep, but his mother sensed his intelligence and made sure he would attend school.

From there he moved on to Prague to further his studies. Having noticed a newspaper advertisement for steerage on SS Westphalia from Hamburg to New York, he sold his belongings and bought a one-way ticket to America.

He landed at Castle Garden in 1874, fifteen-years old, without a penny in his pocket and unable to communicate in English.

He landed at Castle Garden in 1874, fifteen-years old, without a penny in his pocket and unable to communicate in English.

Having settled into a regular job, he took advantage of free evening classes at the Cooper Union which sparked his ambition. He attended Columbia College on a scholarship and graduated with honors in 1883.

He earned his doctorate in mathematical physics at the University of Berlin in 1889, before returning to Columbia where he would make an illustrious career.

In 1924 Pupin won the Pulitzer Prize for his autobiography From Immigrant to Inventor which tells of his transformation into one of the nation’s pioneering electrical engineers and inventors (holder of thirty-four patents).

Cooper’s intervention had made it all possible. In 1859, the latter’s pedagogical goal had been forward looking and relevant to a mixed urban society. In our era of renewed sectarianism and bigotry this approach may strike many observers as visionary.

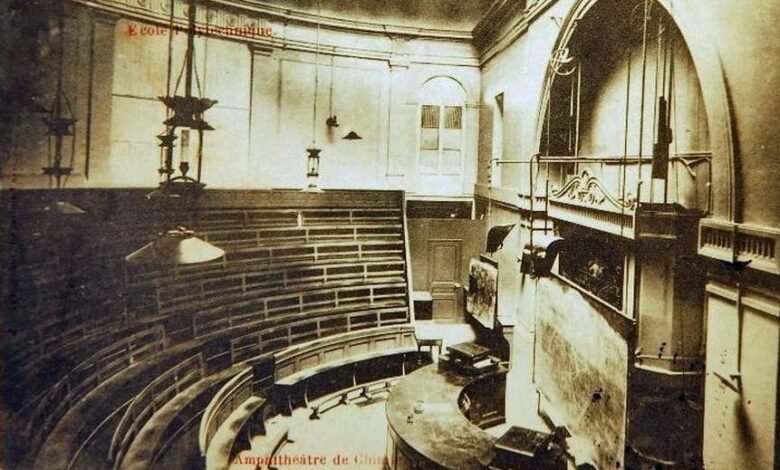

Illustrations, from above: The chemistry auditorium in the old building of the École polytechnique photographed by Jules David in 1904; Frank Hazell’s West Point travel poster for the New York Central Railroad (Latham Lithography, Long Island City); “Brevet Brigadier General Sylvanus Thayer” by Robert W. Weir, ca. 1845 (West Point Museum); “Pour la Patrie, les Sciences et la Gloire” replica of the original sculpture from the École Polytechnique at West Point; Portrait of Peter Cooper, ca. 1870; North Side of The Cooper Union at Cooper Square and Astor Place in 2019 (the original building did not include the peaked roofs or high-rise addition at the rear); and Mihajlo Pupin in 1916.

Source link