New Yorkers Exiled to Tasmania for the 1837-38 Canadian Patriot Rebellion

On September 30, 1970, in a simple ceremony, a monument was unveiled at Sandy Bay Beach Reserve in Hobart, Tasmania, by the Honorable Douglas Harkness, the former Canadian defense minister. It was in honor to the ninety-two Patriot exiles, transported to what was then called Van Diemen’s Land who had been captured in the 1837-38 Patriot War insurrection in Upper Canada against British domination.

On September 30, 1970, in a simple ceremony, a monument was unveiled at Sandy Bay Beach Reserve in Hobart, Tasmania, by the Honorable Douglas Harkness, the former Canadian defense minister. It was in honor to the ninety-two Patriot exiles, transported to what was then called Van Diemen’s Land who had been captured in the 1837-38 Patriot War insurrection in Upper Canada against British domination.

Listed as Canadian rebels, a majority were in fact from the state of New York. Although imprisoned US citizens captured in the various conflicts with England – from the American Revolution to the War of 1812– was not a novelty, it was to be the first time that American prisoners were shipped to a penal colony in Australia due to a confrontation with the Empire.

Ironically, the plight of the exiled Americans had roots in events in the United States. Inspired by the French and American Revolutions, the road to seek representation in the neighboring provinces of Lower and Upper Canada (present day Quebec and Ontario) sparked the 1837-38 rebellions in response to an overbearing and undemocratic system of government imposed by the British.

These frustrations resulted in pitched battles at St-Denis-sur-Richelieu, St-Charles and Saint-Eustache that played out in the months of November and December 1837 between the Patriot Forces and British Troops. In Toronto, rebels skirmished with loyalist militias at Montgomery’s Tavern.

These frustrations resulted in pitched battles at St-Denis-sur-Richelieu, St-Charles and Saint-Eustache that played out in the months of November and December 1837 between the Patriot Forces and British Troops. In Toronto, rebels skirmished with loyalist militias at Montgomery’s Tavern.

The outcome of the 1837 Insurrection was a victory for the Empire. The year after saw more insurrection with the same outcome. The Battles at Odelltown, Beauharnois, Windmill Point and Windsor were brief; the longest lasting a mere few days. The many that fought for change and equality were either killed or captured.

The Canadian Patriot cause inspired many Americans the follow the example of Texas, which had broken from Mexico in 1836. During the 1837-38 rebellions they kept the struggle alive in conjunction with the many exiled Patriots in the United States.

Some came to Vermont and New York where they formed a “Hunters’ Lodge” and launched 17 cross-border raids, without the approval of the US government.

These raids culminated in the November 1838 Battle of the Windmill (at present day Prescott, Ontario) with the majority of the 190 raiders taken prisoner. Tied by rope in single file, they were marched to a steamer and taken to Fort Henry, in Kingston, Ontario. Sixty of those men were from the Hunters’ Lodge, it would be their first of many journeys.

These raids culminated in the November 1838 Battle of the Windmill (at present day Prescott, Ontario) with the majority of the 190 raiders taken prisoner. Tied by rope in single file, they were marched to a steamer and taken to Fort Henry, in Kingston, Ontario. Sixty of those men were from the Hunters’ Lodge, it would be their first of many journeys.

The bloody Battle of the Windmill moved the US government address its neutrality agreement with the Canadian provinces. On November 21, 1838, US President Martin Van Buren stated that any American citizen would lose their right to protection and would not receive legal assistance from the United States government if invading a friendly nation, a violation of the country’s Neutrality Act of 1818.

Despite this warning, American Patriots continued their fight alongside their Canadian compatriots, receiving their final blow at the Battle of Windsor in December 1838, with many being captured by Upper Canadian Militia troops. Five Americans were executed after the battle.

In all, about 50 US citizens were killed in the 1838 conflicts. Ultimately 12 Lower Canadians, and 17 in Upper Canada were hung for their participation in the failed 1838 insurrections -four of those coming from the town of Lyme, in Jefferson County, New York.

To avoid backlash, further executions ceased. Conditional pardons were granted to some prisoners. But 58 captives remained in Lower Canada, while 79 — the majority of whom were Americans who fought for the cause — were still incarcerated in Upper Canada.

Upper Canadian Lieutenant-Governor Sir George Arthur, who previously served as Lieutenant-Governor of the notorious penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land (1825-1856, present day Tasmania) proposed a solution to the Patriot prisoner dilemma: to send them to his former post.

Upper Canadian Lieutenant-Governor Sir George Arthur, who previously served as Lieutenant-Governor of the notorious penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land (1825-1856, present day Tasmania) proposed a solution to the Patriot prisoner dilemma: to send them to his former post.

At the time, the Australian penal colonies formed a dumping ground not only for criminals but also for political prisoners from all across the British Empire -the Guantanamo Bay of the 19th century. This was to be the final destination for the Americans and Lower-Upper Canadians as exiles.

On September 22, 1839, the 79 Patriot prisoners (and four non-political) were escorted by troops from Fort Henry to the Kingston wharf. Out of that number, 72 had come from the United States, such as New York State natives Robert Collins, Ira Polley and Hiram Sharp, all captured in the Battle of the Windmill. They were loaded on Durham boats towed by a small steamer for the first leg of their journey Down Under.

Fearing an armed intervention from the American side of the Saint Lawrence River, the boats were towed through the various locks and canals of the Rideau Canal, which had opened in 1832. They then went down the Ottawa River, making a stop at the Montreal port via the Lachine Canal (completed in 1824).

Boarding a steam boat the St. George, the prisoners were then transported up the Saint Lawrence River to Quebec City, embarking on the ship HMS Buffalo at 7 pm on September 27th. Awaiting them below deck were the 58 Lower Canadian Patriots bound for the penal colony of New South Wales (one of them a Vermonter). The Buffalo embarked on its five-month voyage.

To prevent a rumored mutiny, shipboard authorities kept the prisoners confined below-decks in the ship’s sweltering hold, allowing them only brief exercise periods in the fresh air. One American Patriot prisoner Asa Priest, a resident of Auburn, NY, died as a result of these conditions and buried at sea.

At last, on February 12, 1840, the Buffalo reached Hobart Town (Present day Hobart), Van Diemen’s Land. Three days later, the prisoners were unloaded off the ship and ferried in a barge and two row boats to the town’s main wharf. Their reception from the chief administrator was far from pleasant.

At last, on February 12, 1840, the Buffalo reached Hobart Town (Present day Hobart), Van Diemen’s Land. Three days later, the prisoners were unloaded off the ship and ferried in a barge and two row boats to the town’s main wharf. Their reception from the chief administrator was far from pleasant.

According to the memoirs of prisoner Robert Marsh, a native of Niagara County, NY, the island’s Lieutenant-Governor and Sir George Arthur’s replacement, Sir John Franklin, held contempt for the Patriots.

After hearing that the vast majority of the prisoners from Upper Canada were Americans he was said to have exclaimed: “So much the worse. You Yankee sympathizers must expect to be punished. I do not consider the simple Canadians, especially the French in Lower Canada, so much to blame, as they have been excited to rebellion by you Yankees.”

Franklin was quickly despised by these new prisoners. In 1843, he was relieved of his duties there, and perished in the Canadian Arctic in 1847 while leading a doomed expedition in search of the Northwest Passage.

For the exiles, it was to be first time putting their feet on dry land since leaving Kingston, Upper Canada on September 22, 1839. Marched to the Sandy Bay Probation Station near Hobart Town, the now 78 (out of the original 79) Patriots joined the ranks of their 13 others who had already arrived.

One of those 13 was Chautanqua, NY, native Linus Miller, captured in the June 1838 Short Hills Raid. For the Americans, they now had to face the reality of being exiled in a faraway place with no support from their Government.

One of those 13 was Chautanqua, NY, native Linus Miller, captured in the June 1838 Short Hills Raid. For the Americans, they now had to face the reality of being exiled in a faraway place with no support from their Government.

Given Political prisoner status, the Patriots set out building a stretch of road at Sandy Bay. Elizur Stevens, from Lebanon, Madison County, New York, explained the daily routine by saying “our work consists of pecking stones and earth, shoveling, hauling with handcarts, etc. We have to work 11 hours in the day, for 5½ days in the week.”

Although Political prisoners were generally treated better than “common convicts,” conditions were still challenging. Rain and snowy weather had added to their hardships; and they were often forced into humiliating tasks.

It was only a matter of time though before a bid for freedom was made. On June 9, 1840, four Americans made an escape attempt from the Sandy Bay Probation Station. Captured days later, they were sent out as second offenders to the infamous Port Arthur Penitentiary, named after the notorious Sir George Arthur himself – the same man who recommended sending the Patriots to Australia.

Fearing further escapes, the Political prisoners were moved that month inland to the Lovely Banks probation station, 35 miles north of Hobart Town. Stone huts were used to house the prisoners who were put to work in constructing a road to Launceston.

In spite of the precautions taken, two more Americans, New York native Linus Miller and Joseph Stewart, made a break from the Probation Station on August 29, 1840. They were captured September 11th, sentenced to hard labor out of chains.

They were first taken to Hobart Town Prisoner’s Barracks (aka “The Tench”) where they experienced firsthand a dreaded punishment – the treadmill. Thereafter sent to Port Arthur, they were forced to wear humiliating convict “magpie” outfits.

They were first taken to Hobart Town Prisoner’s Barracks (aka “The Tench”) where they experienced firsthand a dreaded punishment – the treadmill. Thereafter sent to Port Arthur, they were forced to wear humiliating convict “magpie” outfits.

On September 12,1840 the Patriots (including Robert Collins, Ira Polley and Hiram Sharp) were moved to the Green Ponds Probation Station to conduct roadwork, build bridges and to construct the St. Mary’s Anglican Church. Here conditions were abominable. For nearly a year they lived in desolate timber slab huts without fireplaces, infested with vermin.

In May 1841, the Patriots had a brief stay at the Bridgewater Probation Station, located eleven miles north of Hobart Town, carrying the reputation for it’s harshness to prisoners. Constructing a causeway across the Derwent River, they worked for the first time among 300 British convicts witnessing the harsher treatment given to the common felon.

One American stated that out of all his time in captivity, his darkest was the 16 days spent at Bridgewater due to working with what he described as “The dregs of the vilest of the vile.”

On May 29th the Political prisoners were broken into smaller groups and spread across the island to the Jericho, Jerusalem, Rocky Hills, Saltwater Creek, New Town Bay, Victoria Valley, Seven Mile Creek, Marlborough and Brown’s River Probation Stations.

Tickets-of-leave were issued to the Patriots between 1841 and 1842 after serving their time to the colony, giving them the freedom to work for employment. Although they were finally able to leave the Probation Stations, they still banished from returning to North America.

Some remained determined to return to their homeland. Ultimately, three escaped on American whaling vessels, in spite of warnings given Captains about the repercussions for taking-on escaped prisoners. The remaining Yankee prisoners struggled on, with nine dying.

In the early 1840s some American politicians, including President Van Buren’s son, John Van Buren, actively lobbied British ministers for the return of the American prisoners. In November 1843, a US Consulate was opened up in Hobart Town to provide assistance to the exiled Americans.

Finally, in early 1844, amnesty was give to all the Patriots in Australia after a strong international outcry for keeping Political prisoners as convicts. By the time this announcement reached Van Diemen’s Land, a dozen Patriots had died in exile on the island.

Forty are known to have received pardons, with the majority returning to the United States and the Province of Canada between 1844 and 1850. John Berry, a native of Columbia County, NY, was the last exile to return in July 1860.

In total, nine Americans are known to have remained at Van Diemen’s Land. This included Robert Collins of Ogdensburg, New York, who married and eventually died there in 1855, being buried in the St. Andrews Presbyterian Church cemetery along with his baby daughter. Three others also had married and settled on the island, such as former Lyme, NY resident, Chauncey Bugby.

In total, nine Americans are known to have remained at Van Diemen’s Land. This included Robert Collins of Ogdensburg, New York, who married and eventually died there in 1855, being buried in the St. Andrews Presbyterian Church cemetery along with his baby daughter. Three others also had married and settled on the island, such as former Lyme, NY resident, Chauncey Bugby.

For the first wave of 27 freed Patriots returning to America, one chose to return to Australia instead. Ira Polley, also from Lyme, was one such case. While at his Oahu stop-over, for reasons unknown, he subsequently took a ship bound to the colony of New South Wales. His fellow American Hiram Sharp of Salina, Onondaga County, NY, had also chose the path of no return departing Van Diemen’s Land in August 1846 and joining Ira Polley in Sydney.

With high unemployment rocking the main city of New South Wales, Polley and Sharp found there way to the Illawara district near Mount Kembla, and were employed cutting cedar with American axes in an area conveniently known as “American Creek.”

There they labored along side with Joseph Marceau, a former Patriot from Lower Canada. In an ironic twist, the three had shared their journey on HMS Buffalo, though strictly segregated between English and French speaking prisoners.

Tragically, Hiram Sharp died in a drowning accident in 1859 at Crankie’s Plains, Bombala, and was buried in an unmarked grave at Nimmitabel. Ira Polley passed away in January 1898 and buried at the Congregational section of Wollongong’s Cemetery in an unmarked grave as well.

Today the descendants of these Patriot exiles live throughout Australia and New Zealand, carrying the surnames of their American and French Canadian ancestors, keeping their memory alive.

For the returning Patriots in North America, various stories of their Australian saga were to come out to the public. A total of 11 exiles wrote accounts or diaries of their convict experiences on the Penal colony.

Three of these are much referenced by researchers, including Notes of an Exile in Van Diemen’s Land (1846) by New Yorker Linus Miller, published in 1846. The first run of his book quickly sold out and he spoke out against the inhumanity of that place he called home for four years.

Miller’s wishes to see the end of cruelty there would eventually be fulfilled when the transportation of convicts to Van Diemen’s Land ceased in 1853. The convict system in Australia itself was finally abolished in 1868.

As for the Patriot cause in Canada which the “Yankee Patriots” had fought and died for, England granted Responsible Government to the Province of Canada in 1849. This semi-autonomous relationship proving successful, the same status was then given to New South Wales in 1855 and Van Diemen’s Land in 1856 (it was officially renamed Tasmania the year before).

In Hobart, the memory of the exiles continues to be honored. The Sandy Beach monument erected in September 1970, was relocated to a more historically relevant area where the Yankees had built one the city’s thoroughfares in 2017.

In Hobart, the memory of the exiles continues to be honored. The Sandy Beach monument erected in September 1970, was relocated to a more historically relevant area where the Yankees had built one the city’s thoroughfares in 2017.

At the official unveiling at the new location on February 17, 2015, Australian descendants of the Americans were in attendance, including Maureen Polley, great-granddaughter of Ira Polley.

(Another monument to the 92 exiles was erected in Princes Park in 1995 not far from where the Patriots disembarked in 1840.)

who received the spotlight. In April 2000 in Tasmania a third monument was unveiled in Hobart in front of the former convict burial grounds and barracks.

A poem by New York Patriot Linus Miller is inscribed on it, dedicated to his fellow prisoners buried there (the spot is now a school yard). In 2015, his plight was featured in a segment of the Australian documentary Death or Liberty showcasing the history of convict rebels in Australia.

In Port Arthur – where he served two years’ hard labor – his image and a quote don a museum exhibit room: “After all my sufferings, to find such a home, and friends, in such a land, was indeed most fortunate.”

Today the former US Consulate in Hobart is the only marked establishment in the capital city bearing witness to the American Patriot legacy in the area. Other spots also bearing evidence to the exiles include the Green Ponds (present day Kempton) St. Mary’s Anglican Church, the roads and bridges the prisoners built and the remains of some of the Probation Stations where they were held.

In the United States, besides the 1951 film Quebec – a Hollywood treatment off the 1837 Lower Canadian Rebellion – and the accounts written by former American exiles, knowledge of the Yankee Patriots remains obscure in the United States. Even more so for the Americans sent as convicts to Van Diemen’s Land.

“By the sacrifices they made by fighting bravely for their ideals, these French Canadian Patriots and the Yankee Patriots… helped build Responsible Government and democracy both in Canada and Australia,” says Australian historian Tony Moore, author of Death or Liberty: Rebel Exiles in Australia 1788 – 1868 (2010).

.

“For in Australia, we did not need that Revolution to get Responsible Government because of what had happened in Canada,” he says. “So in a way these Americans and Canadians are Australian Patriots too.”

Deke Richards is a documentary filmmaker working on a new film about the Patriot exiles.

Read more about the Patriot War of 1837-38

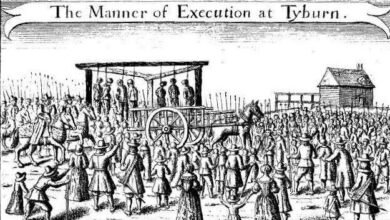

Illustrations, from above: HMS Buffalo at sea; Canadian and American patriots at Windsor, Ontario; the Battle of the Windmill; Hobart Town in 1851 (State Library of New South Wales); portrait of Linus Miller; Prisoners wearing the magpie prison garb, drawn and engraved by John Carmichael, Sydney; St. Marys Church in Green Ponds, Tasmania, 2023; and the Hobart monument unveiling in September 1970.

Source link