New York City Development Rights Transfers Having Big Year

The air rights revolution was just getting started when The Real Deal covered it in June. At that time, however, the evidence was anecdotal.

Now we have data.

Development rights transfers are on pace to increase by 39 percent this year and to reach their highest level since 2016, according to PropertyScout CEO Wilson Parry.

The jump will actually be much higher, broker Bob Knakal predicted, because so many deals are pending.

“It’s off the charts,” Knakal said. “By the end of the year it’s going to be triple what it was last year.”

“The assemblage game has totally changed.”

Credit the City of Yes legislation, passed last fall, which greatly increased property owners’ ability to sell their unused development rights, and last month’s Midtown South rezoning, which gave buildings in the neighborhood more of them to sell.

City of Yes eased air-rights transfers for split districts and landmarked properties, and introduced more flexible zoning envelopes, giving developers more ability to use air rights.

For example, to build a tower on an Upper East Side avenue, one can now purchase development rights from scores of townhomes on lower-density side streets nearby.

A typical Upper East Side townhouse might have 2,000 to 4,000 square feet of unused air rights, sometimes more. That can add two to four apartments to a project that buys them.

A development site can also now shop for landmarked properties’ air rights from an area about 10 times larger than before.

“You used to have two or three potential buyers of your air rights,” Knakal said. “Now you have 30 or 40.”

Landmark air rights are said to be selling for $180 to $400 per square foot of zoning floor area, meaning buildable square footage, but generally for $200 to $250. If a developer has a site worth $500 a foot, and can buy air rights for $250 a foot, the path to a deal is clear.

The other two types of transfers liberalized by the City of Yes were Zoning Law Development Agreements, or ZLDAs (pronounced zeldas), and special district transfers. The latter might allow a Theater District property to sell development rights to any of several dozen parcels.

To take advantage of the changes, Genessy Jaramillo, a managing director at Knakal’s shop, BKREA, is exclusively working on air-rights deals. “It’s on fire,” said. “It’s a no-brainer to be in this niche right now.”

Developers and investment sales brokers, not property owners, are driving the activity. Many owners don’t even know they have air rights to sell, or that they can now transfer them to parcels farther away than just next door or across the street.

Their ignorance is understandable. Air rights are an esoteric concept that few New Yorkers pay attention to, if they have heard of it at all. It never comes up in media appearances by Mayor Eric Adams because it is too far in the weeds for a general audience.

As a result, what the air rights revolution means for real estate and the city’s skyline has been entirely overlooked by the mainstream media — and to a large extent by industry publications, too.

Not by the industry, though.

“The assemblage game has totally changed with this,” Parry said. “Any developer that’s doing something in Manhattan is definitely keen to this.”

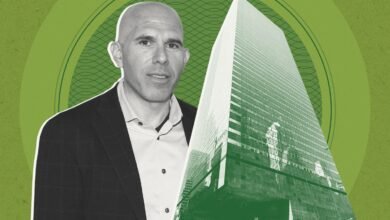

He can see their excitement from the vantage point of his business. PropertyScout subscriptions have more than tripled in part because its software lets users see what unused air rights any Manhattan property has and where they can be transferred.

Parry has been fielding calls from users who reach the maximum number of daily property searches — typically 50 — allowed by their subscription tier and plead for an exception to see more.

“It’s like a toy, what you built,” one told him. “It’s like a game.”

The City of Yes has made the assemblage game more fun for builders and brokers. For example, clicking on a landmarked property now highlights a plethora of parcels that can buy its air rights, instead of merely several.

“It went from four to six lots before City of Yes to like 60,” Parry said. “It’s a 10x increase.”

Surges in development-rights transfers previously occurred from 2005 to 2007 (averaging 115 per year) and from 2013 to 2016 (averaging 109), triggered by a combination of high land prices and rising applications for new buildings, Parry reported on LinkedIn.

Start today for only $1

This year’s projected total of 92 is probably understated, as Knakal noted, because transfers involving landmarked properties take longer than for the two other types. Dozens of these transfers are said to be in the works but had not been recorded yet when Parry tallied the numbers through Aug. 1.

“Landmark expansion hasn’t shown up yet,” Parry said, citing a certification step that delays deals. “It’s lagging.”

Prior to the law changing, only 15 landmark transfers happened in 50 years. “Before the City of Yes, the landmarks transfer was a total failure,” Parry said.

Not only were transfer options limited to a few properties for each landmark, but the process was cumbersome and expensive. It required a special permit, which involves a public review and City Council approval.

Certification is now much easier: The Department of City Planning takes the potential deal to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which verifies that the seller has a plan to maintain the historic property.

“What used to take a couple of years now takes six to nine months,” Knakal said, adding that a seller can close in 60 to 90 days and leave the certification process to the buyer.

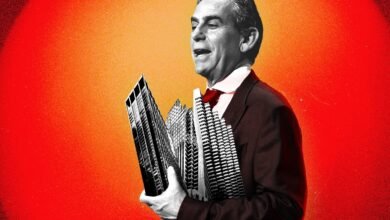

The longtime broker, famed for his “map room” of Manhattan properties, has charted every landmarked building south of 96th Street.

“We’re calling all those owners,” he said. “We have real estate professionals selling air rights, institutions selling air rights, public companies selling air rights, and we have the proverbial little old ladies selling air rights.”

Knakal’s pitch to property owners is fairly simple: There’s no way to monetize air rights without selling them, and selling them doesn’t reduce a building’s revenue.

Manhattan has 1,220 landmarked buildings. The new law changed the rules for individual landmarks, not all properties in historic districts.

Air rights do not automatically allow developers to build bigger projects. Height limits, setback requirements, street wall parameters and other factors collectively determine a site’s potential. A massing study must be done to lay out the possibilities.

Figuring that out, and how to transfer air rights to where you want them, “is like three-dimensional chess,” Knakal said.

Read more

City of Yes spurs Manhattan air rights gold rush

The Daily Dirt: Unlocking air rights throughout the city

Ken Griffin agrees to $78M deal for more church air rights