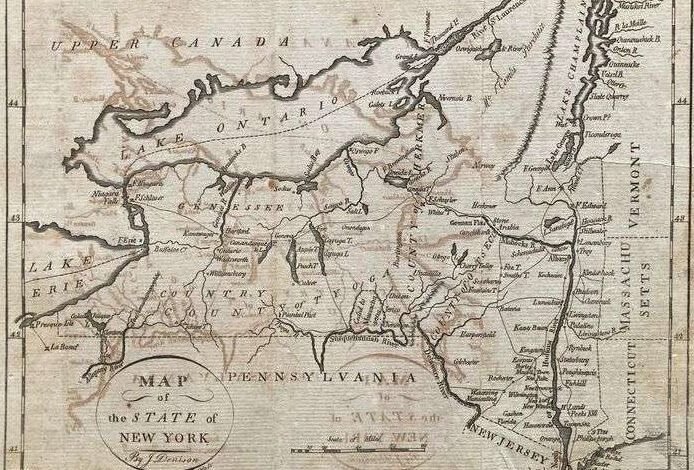

Maps and Geography: Early NYS Transportation History

Years of fighting land wars in the colonies had shaped American thinking around transporting large groups of people, a line of thought that led directly to the construction of the Erie Canal.

Years of fighting land wars in the colonies had shaped American thinking around transporting large groups of people, a line of thought that led directly to the construction of the Erie Canal.

As American colonists pushed west, their efforts to connect people and products also resulted in considerable exploration and alteration of the land, some reflection on man-made impacts, and the production of maps, sketches, and more documents that help us tell the story of early New York State and the Erie Canal.

Moving People

Before the Erie Canal, colonists used ancient Native American trade routes that followed New York’s natural waterways. Turnpikes, or toll roads, were in use by 1800, but were not much more than dirt paths. The turnpikes were ill-suited for the large-scale commerce by land that the young nation very much demanded.

In addition, the experience of trying to move large numbers of soldiers and equipment between Albany and Oswego during the French and Indian War (1755-1763) prompted new conversations about building a canal between Albany and Lake Ontario and between Albany and Lake George.

The map below, titled “Communication Between Albany and Oswego,” was printed in a history of the war published in 1772. It illustrates the dramatic twists and turns of the natural water route from Albany to Oswego.

The complete book, The History of the Late War in North-America, and the Islands of the West-Indies Including the Campaigns of MDCCLXIII and MDCCLXIV Against His Majesty’s Indian Enemies, is available to view in the NYS Library’s Digital Collections.

In addition to the twisting waterways, colonists faced a considerable barrier to westward expansion in the Appalachian Mountains, which cut off easy access to the interior of the continent from Georgia to just south of the Mohawk River in New York.

However, the people living in the colony of New York had the distinct advantage of the break in the mountains that ran along what we now call the Hudson and Mohawk valleys. That break is visible in this photograph, which features a relief model map created in 1897.

The shading on the mountain ranges provides a good illustration of the break in the river valleys that allowed people to move westward. You can view a larger version in the NYS Library’s Digital Collections.

The shading on the mountain ranges provides a good illustration of the break in the river valleys that allowed people to move westward. You can view a larger version in the NYS Library’s Digital Collections.

Moving Land

Even with the convenient break in the mountains, constructing the Erie Canal meant making considerable alterations to the rugged natural makeup of New York State.

Large swaths of forested land were cleared to make way for the canal. This activity and its impacts had different effects on those who encountered the new landscape.

In 1829, Basil Hall published forty illustrations of landscapes in North America, which he had captured during trips he made in 1827 and 1828.

The book, Forty etchings from sketches made with the camera lucida, in North America, in 1827 and 1828, is available in its entirety in the NYS Library’s Digital Collections.

It includes many breathtaking views of the natural landscape and some detailed scenes of towns, cities, and fledgling infrastructure taking shape across New York State.

Illustration IX, titled “Newly Cleared Land in America,” depicts cleared land in Ridgeway, New York, 40 miles west of Rochester.

Illustration IX, titled “Newly Cleared Land in America,” depicts cleared land in Ridgeway, New York, 40 miles west of Rochester.

The image captures the stumps of a cleared forest with some signs of human habitation at the edges, including fences, a small structure, and domestic animals.

Hall introduced this etching with the following commentary:

“The newly-cleared lands in America have, almost invariably, a bleak, hopeless aspect. The trees are cut over the height of three or four feet from the ground, and the stumps are left for many years till the roots rot; – the edge of the forest, opened for the first time to the light of the sun, looks cold and raw; – the ground, rugged and ill-dressed, has a most unsatisfactory appearance, as if nothing could ever be made to spring from it.”

Cadwallader D. Colden, a stockholder in the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company and enthusiastic Erie Canal supporter, had a much different reaction to such scenes in New York State. In 1825, Colden wrote:

“Indeed, to see a forest tree, which had withstood the elements till it attained maturity, torn up by its roots, and bending itself to the earth, in obedience to the command of man, is a spectacle that must awaken feelings of gratitude to that Being, who has bestowed on his creatures so much power and wisdom.”

Cadwallader D. Colden appears on the “pillar of faces” dedicated to the Erie Canal’s supporters, as does his grandfather, Cadwallader Colden, a surveyor-general of the Province of New York and early advocate for improved internal navigation to support trade.

In Lockport, a village that sat 30 feet above the canal’s water level, thousands of workers used wooden beams, ropes, oxen, horses, gunpowder, shovels, picks, and wheelbarrows to excavate a three-mile section of the canal that ran through solid rock.

In Lockport, a village that sat 30 feet above the canal’s water level, thousands of workers used wooden beams, ropes, oxen, horses, gunpowder, shovels, picks, and wheelbarrows to excavate a three-mile section of the canal that ran through solid rock.

This work and its result are well documented in Cadwallader D. Colden’s Memoir, Prepared at the Request of a Committee of the Common Council of the City of New York and Presented to the Mayor of the City, at the Celebration of the Completion of the New York Canals, available to view in our Digital Collections.

Displacement

The story of the Erie Canal’s construction is trailed by a complicated legacy of manifest destiny and disenfranchisement.

The triumph of the canal project and the westward surge of people seeking land and natural resources devastated Native American communities.

In the name of nation building and progress, these long-standing communities were forced off their ancestral lands and sent to reservations.

Before construction on the canal began, land speculators correctly bet that a canal connecting the Hudson River with Lake Erie would be a good business investment.

They began buying purchasing property with the intent to sell it at a higher price upon completion of the canal.

By 1800, 25 years before the canal would open, various land speculation companies had gained the rights to most of Western New York.

As settlers flocked to the region, they pressured the government to make more land available and, by 1870, only a few small reservations remained.

Maps at the NYS Library

When the NYS Library opened in 1818, it was home to 669 volumes and only nine maps. In just three years, the collections grew to over a thousand volumes and a few hundred pamphlets (and, presumably, maps).

This growth in collections speaks both to DeWitt Clinton’s efforts to amass an impressive and useful collection of books (largely through gifts) and to the studies, surveys, and mapmaking activities that the government undertook during the 1800s.

New York State did not content itself with completing a massive feat of engineering in the 1800s. In fact, as part of the surge of nation-building in the former colonies, New York undertook, in the words of historian Cecil R. Roseberry, “a significant and pioneering work in the field of science.”

The Natural History of New York grew from the Natural History Survey launched by the NYS Legislature in 1836. That same year, the first geologic reports were added to the NYS Library’s shelves.

Today you can view sections from the Natural History of New York in the NYS Library’s Digital Collections. The section on Geology in particular includes detailed maps and drawings.

Today, the NYS Library houses a wide selection of maps from the state’s history, including military and political maps; land patents, records, and surveys; and many maps produced by the Federal government and New York State government.

Check out the Library’s Annotated Bibliography of Selected New York State Maps: 1793-1900.

You can find tips on finding maps at the New York Almanack here.

Further Downstream

The development of the Erie Canal carried the U.S. further and further from the years of the French and Indian War, the American Revolution, and the War of 1812.

The completion of the canal was an unprecedented and unparalleled cause for celebration, and New Yorkers took every opportunity to observe the occasion.

Read more about New York’s transportation history.

This essay was first published on the New York State Library Blog. The New York State Library, established by law in 1818, collects, preserves and makes available materials that support State government work. The Library’s collections, now numbering over 20 million items, may also be used by other researchers on-site, online and via interlibrary loan.

Illustrations, from above: 1796 map of New York by Denison, Morse and Doolittle; “Communication Between Albany and Oswego,” a map printed in a history of the French and Indian War published in 1772; 1897 New York State Relief Map (NYS Library); “Newly Cleared Land in America,” showing cleared land in Ridgeway, NY, 40 miles west of Rochester, 1827-28; and “Process of Excavation at Lockport” showing the Erie Canal being built, from Colden’s memoir (NYS Library).

Source link