Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, Thomas Nast & Chinese American History

Migration from Asia to the United States was minimal before the 1800s, but facing poverty and political instability large numbers of Chinese residents began looking a better life in the West from the 1840s onward.

Migration from Asia to the United States was minimal before the 1800s, but facing poverty and political instability large numbers of Chinese residents began looking a better life in the West from the 1840s onward.

Many would escape the Taiping Rebellion, a large-scale civil war that had started in 1850. Lasting for fourteen years, violence and persecution encompassed much of Southern China, pushing citizens away from their traditional homes.

After German-born Swiss immigrant John Augustus Sutter discovered gold in 1848 at Sutter’s Mill, Sacramento, rumor spread about a promised land of riches. Migrants rushed to California en masse. By 1851, twenty-five thousand Chinese incomers had settled there; three decades later a quarter of the state’s workforce was Chinese.

Gold Mountain & John Chinaman

Workers arrived with high hopes, referring to their new Californian home as Gold Mountain (Gum Shan in Cantonese). Every migrant dreamed of becoming a “Gold Mountain Man.” The metaphor signified the potential of opportunity that pulled many to seek their fortunes in the West.

While some immigrants did find success, many faced the harsh realities of discrimination, brutal working conditions and the separation from their families.

Throughout the 1850s and 1860s Chinese men were recruited either as miners or workers on the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. Local employers appreciated their cheap labor, work ethic and skills, breeding resentment among white workers.

The stand-off provoked regular disputes and conflicts. Most migrants planned to return home at some time and there was little motivation for them to assimilate. After completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, job security was at risk. By the 1870s, the economy was in a post-Civil War decline. The country experienced a series of financial crises, starting with the Panic of 1873.

The depression that followed caused income levels to fall and many laborers were sacked. In California, white workers competed for scarce jobs with Chinese migrants who would work for lower wages. They became political scapegoats, being blamed for unemployment and accused of stealing American jobs. Public opinion turned against “John Chinaman.” Stereotypes and bigotry loomed large. Discrimination became endemic.

Perceived as “totally unassimilable,” Chinese men were abused for their short stature, traditional pony-tailed hairstyles and “effeminacy.” Opium smokers and gamblers, they were considered an immoral lot. Campaigns were started to expel them from the labor market.

Social unrest led to the passing of a series of anti-Chinese legislative measures from the 1850s onward, culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which was the first law in American history to ban a specific racial group from entering the country.

Turning diverse groups of immigrants against one another became a political strategy. The phrase a “nation of immigrants” is based on a very selective historical narrative.

Early legal interventions were attempts to suppress the use of drugs. Many immigrants descended from Canton, a region with a long history of opium addiction. By 1875, anxious authorities in San Francisco issued an ordinance prohibiting opium dens (America’s first anti-narcotics law). As the Chinese presence spread eastwards, edicts banning opium-smoking were issued across the United States as the habit attracted a white clientele as well.

Early legal interventions were attempts to suppress the use of drugs. Many immigrants descended from Canton, a region with a long history of opium addiction. By 1875, anxious authorities in San Francisco issued an ordinance prohibiting opium dens (America’s first anti-narcotics law). As the Chinese presence spread eastwards, edicts banning opium-smoking were issued across the United States as the habit attracted a white clientele as well.

Federal law prohibited Chinese immigrants from becoming naturalized citizens. The 1892 Thomas Geary Act (officially titled: “An Act to prohibit the coming of Chinese laborers to the United States”) required them to carry a residence certificate at all times upon penalty of deportation. To (brutally) enforce the law and restrict entrance, Angel Island Immigration Station was built in San Francisco Bay in 1910.

Thomas Nast’s Cartoons

During the eighteenth century, the political cartoon became a recognized form of socio-political commentary. The British weekly satirical magazine Punch started in 1841, featuring the work of John Leech (1817-1864) whose drawings were the first to be called “cartoons.” John Tenniel (1820-1914) illustrations popularized symbols such as Britannia, John Bull or Uncle Sam.

Under British colonial rule any person who criticized the Crown or government might be imprisoned, but during the American Revolution cartoons became a much used tool in political discourse. With the ratification of the Bill of Rights in 1791, cartoon creation was protected by the First Amendment. The greatest American satirist to emerge was Thomas Nast.

Born on September 27, 1840, in military barracks in Landau, Bavaria, Nast’s father was a trombonist in the Bavarian 9th Regiment band. In trouble for his political views, he sent his wife and children to the city of New York in 1846 where he later joined the family. Thomas was educated in the city, a poor student in academic terms, but a talented illustrator.

After studying at the National Academy of Design, he eventually joined the staff of Harper’s Weekly in 1862. He quickly developed into a sharp political cartoonist, focusing on such topics as the Civil War, slavery, xenophobia, and William “Boss” Tweed’s corrupt rule at Tammany Hall. When Nast died in 1902, The New York Times eulogized him as the “Father of American Political Cartoon.”

A solitary voice, Thomas Nast dedicated forty-six cartoons in Harper’s Weekly defending Chinese Americans. His images were aligned with the journal’s editorial position of inclusion and tolerance towards immigrants.

A solitary voice, Thomas Nast dedicated forty-six cartoons in Harper’s Weekly defending Chinese Americans. His images were aligned with the journal’s editorial position of inclusion and tolerance towards immigrants.

On February 18, 1871, the magazine published an article which dismissed the purported “Chinese invasion” as altogether mythical, arguing that most Americans still adhered to the “old Revolutionary doctrine that all men are free and equal before the law.”

That sentiment is reflected in Nast’s cartoon entitled “The Chinese Question.” The Romanesque goddess Columbia, who preceded Uncle Sam as a symbol of independence, is depicted shielding a Chinese worker from a furious mob (themselves immigrants), with the caption “Hands off, gentlemen! America means fair play for all men.”

Plastered on a wall behind the nurturing figure of Lady Columbia, are slurs that refer to Chinese workers as mongolian, barbarian, heathen, idolatrous and pagan. They are condemned as morally suspect, vicious and vile.

At the time of the cartoon’s publication, New York City’s Chinese population was minuscule.

Exodus to Manhattan

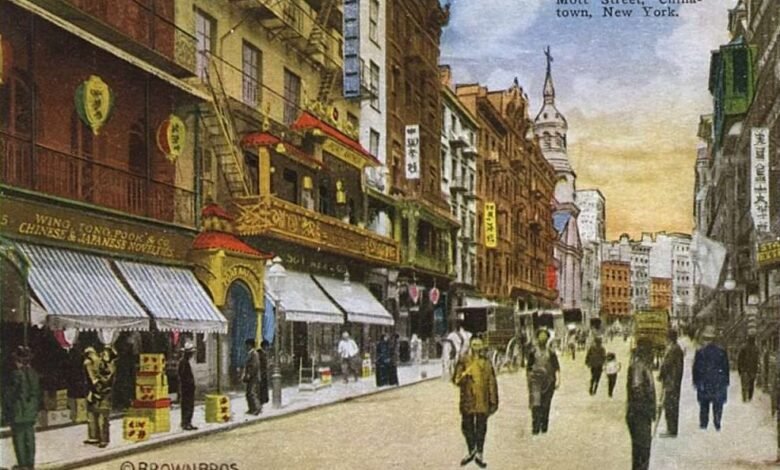

Some early Chinese settlers were sailors and traders who had arrived in New York Harbor and decided to stay, but most residents were refugees from the western United States. Increased mob violence and rampant discrimination in California had driven them to Manhattan where there were job opportunities as well as the relative safety of a more diverse population.

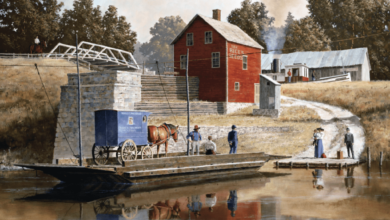

In 1870, less than a hundred Chinese people resided in New York City; two decades later there were about 13,000 living there. From the 1870s onward, Manhattan’s Chinese population began to concentrate around Mott Street. Barred from citizenship and its protections, locals formed their own internal structures that provided jobs, medical care, mutual protection and housing.

The tenement was the district’s predominant type of building and these structures were modified to conform to Chinese uses and tastes. The first genuine such building was the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) at 16 Mott Street.

Considered its “City Hall,” the appointed leader was known as the “Mayor of Chinatown.” The organization mediated in disputes, acted as a broker in business transactions, protected local residents and stood up for their rights.

By the early 1880s, Chinatown was a mini-economy with over three hundred laundries, fifty vegetable markets, twenty tobacco stores, ten pharmacies, six restaurants, and numerous opium dens and brothels. By then, the Chinese owned almost every building on Mott Street. Known as “China Town” (the term was introduced by The New York Times in 1880), the quarter counted a number of secret societies and rival gangs fighting for dominance in an almost exclusively male society.

This type of mayhem offered juicy material to reporters. The Police Gazette was a tabloid-like magazine that chronicled crime and violent acts for the consumption of New York City’s general public. Its pages were filled with lurid accounts of street battles featuring hatchet-wielding warriors fighting on behalf of Chinese secret societies.

Prejudice and racial discrimination reached every aspect of society in every part of the nation. In 1886, the George Dee Magic Washing Machine Company in Dixon, Illinois, produced a poster with the slogan “Uncle Sam Kicks out the Chinaman,” promoting its new detergent (“Magic Washer”) in an effort to displace Chinese laundry operators.

Prejudice and racial discrimination reached every aspect of society in every part of the nation. In 1886, the George Dee Magic Washing Machine Company in Dixon, Illinois, produced a poster with the slogan “Uncle Sam Kicks out the Chinaman,” promoting its new detergent (“Magic Washer”) in an effort to displace Chinese laundry operators.

Traditionally, Chinese men had left wives and family behind to come to America, hoping to make money and return home later. During the period of anti-Chinese agitation, lawmakers seized upon gender categories to impose social control and close the open borders.

In 1875, Congress passed the Horace Page Act, aiming to “end the danger of cheap Chinese labor and immoral Chinese women.” It specifically barred prostitutes, a vaguely defined category that border agents could apply as they saw fit. Single and unemployed women were qualified as sex workers. Long periods of exclusionary policies led to a severe gender imbalance in Chinese communities.

Deprived of familial ties, men relied on local associations and societies as substitute families or turned to gambling, prostitutes or opium (most arrested Chinese men were accused of one of three criminal acts: visiting brothels, gambling, or using drugs).

Some men married local women, even though an American woman would be deprived of her U.S. citizenship if she did so. Most of these ladies were of Irish background as relationships were driven by a shared experience of discrimination, hostility and exclusion. Intermarriage between Irish women and Chinese men challenged prevailing social norms, creating further racial conflicts and xenophobic hatred.

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

Even though early Chinatown was predominantly a bachelor society, women played a crucial role in its development and evolution. They ran family businesses, worked in restaurants and laundries, maintained religious and cultural traditions, and built local community associations and networks. As the district grew and diversified, women began to take on more leading roles in the community. Some of them became prominent social activists.

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was born on October 7, 1897, in Guangzhou, Canton City. Her father Lee Towe was a clergyman who was called to the United States when she was four years old. By 1904 he acted as pastor of the Baptist Chinese Mission in Chinatown, Manhattan. Mabel stayed in Canton with her mother, but they were able to join him in 1905 after she was awarded a Boxer Indemnity Scholarship (a program for Chinese students to be educated in the United States). She would make her presence felt in the fight for minority rights.

Living in a tenement at 53 Bayard Street, Chinatown, she attended Erasmus Hall Academy on Flatbush Avenue, Brooklyn. Founded in 1786 as a private institution of higher learning named after Desiderius Erasmus, the school served to accommodate the sharp increase of immigrant children. In 1913 Mabel entered Barnard College. Founded in 1889 and affiliated with Columbia University, this woman’s college was one of the original group of liberal arts institutions that made up the so-called “Seven Sisters.”

Living in a tenement at 53 Bayard Street, Chinatown, she attended Erasmus Hall Academy on Flatbush Avenue, Brooklyn. Founded in 1786 as a private institution of higher learning named after Desiderius Erasmus, the school served to accommodate the sharp increase of immigrant children. In 1913 Mabel entered Barnard College. Founded in 1889 and affiliated with Columbia University, this woman’s college was one of the original group of liberal arts institutions that made up the so-called “Seven Sisters.”

As a Chinese immigrant, Mabel was legally unable to vote under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Being denied that right, she became committed to political activism at an early age and tried to inspire other Chinese women to become civically engaged.

At Barnard she joined the Chinese Students’ Association and wrote essays in support of women’s education for The Chinese Students’ Monthly, including one on the “Meaning of Woman Suffrage” (issue of May 1914).

She was already known for her views by then. Two years earlier, she had hit the headlines. On May 4, 1912, riding a white horse, she helped leading a suffrage parade in Manhattan that was attended by some ten thousand people.

By 1917, women in the state of New York were granted the right to vote. Three years later, the Nineteenth Amendment was passed that gave them the right to vote across the country, but not to Mabel and other women of color. She continued to plea for equal rights, but it would take until 1943 for the Chinese Exclusion Act to be repealed.

After graduating from Barnard College, Mabel carried on her studies at Columbia University. In 1921 she became the first Chinese woman to graduate with a PhD in economics. Her thesis was published that same year as a book entitled The Economic History of China: With Special Reference to Agriculture. The study was significant enough to be re-issued in October 2022.

Mabel never betrayed her Manhattan roots and remained involved with its immigrant community. Following her father’s death in 1924, she took over his role as Director of the First Chinese Baptist Church at Pell Street. She opened the Chinese Christian Center, offering a health clinic, a kindergarten, vocational training and English classes to the local community.

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee died in 1966. On December 3, 2018, Chinatown’s Post Office Station at Doyers Street was dedicated to her.

It is not known if she ever attained American citizenship or exercised her right to vote.

Illustrations, from above: Postcard of Mott Street, Chinatown late-19th century, published by Brown Brothers; Anonymous, “Opium den in San Francisco boarding house,” late nineteenth century. (The Bancroft Library); Thomas Nast, “The Chinese Question,” published on February 18, 1871, in Harper’s Weekly; The George Dee Magic Washing Machine Company, “The Chinese Must Go” broadside poster promoting a new detergent, 1886 (Library of Congress); “Chinese Girl Wants Vote” portrait of Mabel Ping-Hua Lee in the New-York Endowment Tribune, April 13, 1912 (Library of Congress).

Source link