Legacy in the Ashes: Victory Mill History Lives On

On June 2, 2025, excavators rolled onto a quiet stretch of Fish Creek to begin dismantling the remains of Victory Mill, the five-story concrete giant that has towered over the Village of Victory since 1918. The demolition comes just days after a devastating fire on May 31, which gutted the dormant factory and ended the physical presence of a structure that once defined the rhythm of life in the Town of Saratoga hamlet.

On June 2, 2025, excavators rolled onto a quiet stretch of Fish Creek to begin dismantling the remains of Victory Mill, the five-story concrete giant that has towered over the Village of Victory since 1918. The demolition comes just days after a devastating fire on May 31, which gutted the dormant factory and ended the physical presence of a structure that once defined the rhythm of life in the Town of Saratoga hamlet.

But as brick crumbles and beams fall, the story of the mill — and the people who built their lives around it—remains firmly intact.

Victory owes its name to the American triumph in the Battles of Saratoga, culminating in the complete surrender of British General John Burgoyne’s army on October 17, 1777. It was a moment that shifted the trajectory of the Revolutionary War and gave the young nation a new hope.

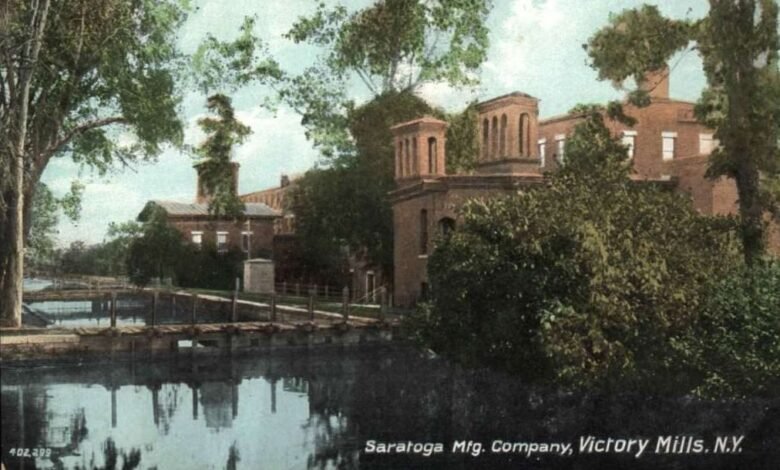

The land along Fish Creek, where Victory Mill would later rise, had already been partly industrialized by General Philip Schuyler, who built an upper sawmill and dam on Lot No. 5 as early as 1768.

After the war, Schuyler’s descendants developed and sold parcels along the creek. By 1828, his grandson, Philip Schuyler II, opened the Horicon Mill — a water-powered cotton factory that began Victory’s industrial identity. The Panic of 1837 eventually forced the sale of the property, opening the door for corporate investment.

In 1846, work began on the first Victory Mill: a three-story brick textile plant designed to take full advantage of Fish Creek’s nearly 100-foot drop. That same year, company housing began to rise, and the village’s population surged. Victory was incorporated in 1849.

By 1850, the Victory Manufacturing Company employed 369 workers — 160 men and 209 women — and operated 309 looms. By the 1870s, the workforce – including many children – had expanded to 550, producing over two million yards of fabric annually.

The factory consumed more than 2,000 bales of cotton each year, and Victory’s fate became bound to the rhythms of the industry: whistle blows, shift changes, and rail deliveries tied it to national markets.

Yet the mill was more than a workplace. It was the heart of a company town. A four-room schoolhouse opened in 1872 and served local children for over 80 years. The company supported churches, built a community house, and created a tight-knit village shaped by labor and mutual reliance. Workers, many of them Irish immigrants, built families and traditions rooted in shared work and faith.

The late 19th century brought upheaval. Labor unrest — including strikes in 1876 and 1879 — coincided with national downturns like the Panic of 1873. By the 1880s, poor management and leadership instability led to inconsistent operations.

A brief resurgence came in 1910 when the American Manufacturing Company of Brooklyn acquired the site and redirected it toward rope and cordage production. With that shift came a monumental physical transformation: the five-story concrete mill and hydroelectric plant construction completed in 1918. A new community house and dance hall followed.

Still, global forces intervened. In 1921, bag-making operations moved to India. By 1928, facing pressure from Southern competition, the company began relocating machinery to Alabama. That fall, 328 carloads of equipment left Victory. Local production halved, and by September 1929, all spinning, carding, and weaving had ceased.

A new chapter began in 1937 when United Board and Carton repurposed the site for cardboard manufacturing. Through changing ownerships — Wheelabrator-Frye, Clevepak, and finally Victory Specialty Packaging — the mill operated into the 1980s. It closed in 2000, ending over 150 years of continuous industry on Fish Creek.

The concrete shell stood for the next two decades — weathered but resolute. In 2008, the site was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places, recognizing its architectural presence and economic impact. Redevelopment plans emerged but never secured funding. And then, on May 31, the fire.

Smoke rolled across the creek as more than 100 firefighters from Schuylerville, Greenwich, Easton, Quaker Springs, Middle Falls, and beyond battled the flames. Residents brought food. Some watched silently, others in tears.

The mill was a ruin, but for many, it was also a relative — a place where grandparents worked, where birthdays were celebrated in the community house, where lives were stitched together over generations.

As demolition crews began their work, the sounds of machinery were less jarring than expected. They seemed almost like an echo — one last call from the mill whistle that once shaped daily life in the village — a final signal, not of labor beginning or ending, but of an era passing.

Yes, Victory Mill was just a building. But it raised families. People earned their first paychecks, built homes, and a sense of pride. And that doesn’t burn away.

The Village of Victory may now face an open space where a factory once stood. However, it still holds something more critical: memory, continuity, and a legacy woven into the soul of Saratoga County.

History doesn’t disappear with demolition. It endures in archives, family stories, the deep curve of Fish Creek, and the firehouses and homes that still carry the name Victory.

Illustration: Victory Mill postcard, ca. 1900.

Source link