Lake George: A 1950s-60s Vacation Paradise

“Gear Up for Tomorrow,” a 1960 newsreel promoting General Electric that was shown in movie theaters throughout the nation, was filmed largely in Lake George, for good reason.

“Gear Up for Tomorrow,” a 1960 newsreel promoting General Electric that was shown in movie theaters throughout the nation, was filmed largely in Lake George, for good reason.

Lake George exemplified the promise of post-War optimism: a material abundance within reach of all and the democratic mobility, upward and outward, symbolized by the automobile and the interstate.

“Welcome to Lake George: Vacation Paradise of the ’50s and ’60s,” the current exhibition at the Bolton Museum in Bolton Landing, is a reflection and exploration of this era in Lake George history.

From Mansions to Motels

After World War II, Lake George’s tourist industry began to change from a summer-long resort for the wealthy to a place where middle class and working families could come by car for a two-week vacation. In 1948, a onetime schoolteacher from Ohio named Earl Woodward bought the Villa Marie Antoinette, which in 1918 cost more than $1 million to build, for $100,000.

After World War II, Lake George’s tourist industry began to change from a summer-long resort for the wealthy to a place where middle class and working families could come by car for a two-week vacation. In 1948, a onetime schoolteacher from Ohio named Earl Woodward bought the Villa Marie Antoinette, which in 1918 cost more than $1 million to build, for $100,000.

As the mansions along “Millionaire’s Row,” as the stretch of highway between Lake George Village and Bolton Landing was known, were sold, the houses were demolished or transformed into lodges and motels, with garages and stables being turned into housekeeping cabins.

For the next decade, Woodward, bought up lake shore estates and subdivided them into cottage colonies. Marcella Sembrich’s former estate became Carey’s, Victorian Village, Twin Bay and the Point. Villa Marie Antoinette was divided into Melody Manor, the Gate House, Bluebird Cottages and Shallow Beach.

Woodward was the father of another innovation in the hospitality industry – the dude ranch. Earl Woodward, who began logging and building in Warren County in the late teens or early 20s, decided that our area was just the place to situate these western-style dude ranches.

Woodward was the father of another innovation in the hospitality industry – the dude ranch. Earl Woodward, who began logging and building in Warren County in the late teens or early 20s, decided that our area was just the place to situate these western-style dude ranches.

At the height of their popularity, there were five dude ranches on the road between Lake Luzerne and Lake George – at least three of which were created by Woodward – not to mention a rodeo and at least ten western-themed bars.

And the Crowds Came

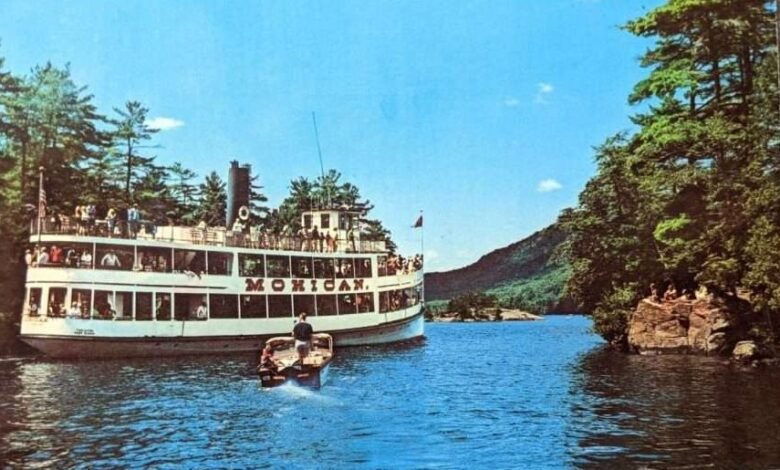

Earl Woodward was clearly aware of the changes brought about by the post-World War II economic boom. So, too, were others. Wilbur Dow, for instance, was a New York admiralty lawyer who bought what remained of the Lake George Steamboat Company – two piers, a marine railway and the Mohican, a 1908 steamboat – in 1945 for $35,000.

Dow saw a future in excursion boats catering to the post-war tourist trade. Under the supervision of Olin Stevens, best known as a designer of America’s Cup yachts, the Mohican was converted from steam to diesel and a new, modernistic superstructure was built.

Transformed into an excursion vessel, the Mohican became a popular tourist attraction, offering visitors trips to the foot of the lake and back as well as shorter cruises to Paradise Bay.

Transformed into an excursion vessel, the Mohican became a popular tourist attraction, offering visitors trips to the foot of the lake and back as well as shorter cruises to Paradise Bay.

Soon, the crowds began to come: from the end of World War II to 1950, 50,000 a year. Record crowds were reported for the 1945 Independence Day weekend, for instance. Reported the Lake George Mirror, “Many more cars are parked on the streets of the village than have been seen here since the war started.”

In 1950, a week’s vacation might cost $25. Most of Lake George remained in a state of nature. Bolton Landing was still a small town. North of Bolton, and the east shore, were even more undisturbed than those places are today.

“The human encroachment, considering the size of the lake, is minor. And from the swankiest lodge it is a matter of minutes across the water to a cove in which you would swear no human has ventured before,” said a Holiday magazine article in 1950.

And as one 1950s magazine article noted, “Every summer, Lake George Village puts on its Cinderella costume of pinball machines, neon lights, penny game-of-skill rooms and has itself a party listening to the cash register. Extra cops are hired against the big summer crowd which squeezes into every available bit of room space and presses through Canada Street, the main thoroughfare, until the amusement places and the drug stores close down.”

Greyhound and Trailways served the resort communities, and as post-war economic prosperity spread, more people began to arrive by automobile. For entrepreneurs, there was money to be made. In 1950, the Surfside Motel in Lake George Village – a motor court, with cabins separated by parking lots – sold for $350,000.

Greyhound and Trailways served the resort communities, and as post-war economic prosperity spread, more people began to arrive by automobile. For entrepreneurs, there was money to be made. In 1950, the Surfside Motel in Lake George Village – a motor court, with cabins separated by parking lots – sold for $350,000.

By 1957, there were 14,000 motel units on Lake George, primarily in Lake George Village. From 1952 to 1957, 2,000 units were built, including 500 in 1956 and 200 in 1957 alone. It’s believed the first motor court in America was Sisson’s, built in Lake George Village in the 1920s, on the site where the Courtyard Marriott now stands.

Motels did not truly become popular, though, until after World War II, when automobile travel became nearly universal. In 1967, the Hotel Antlers on the Bolton Road was purchased for $265,000 and demolished, to be replaced by the lake’s first condos.

Now on View at the Bolton Museum

The exhibit “Welcome to Lake George: Vacation Paradise of the ’50s and ’60s,” is on view through October 12. Colorful displays highlight motels and cabin colonies, nightlife, waterfront recreation, tourist attractions and the coming of the Adirondack Northway (I-87).

Among the features of the exhibition is a collection of gowns and dresses donated by the late Patricia Bixby Hoopes, all of which exemplify the buoyant spirit of the era.

The 1954 Governor’s Conference at the Sagamore, Diane Struble’s length-of-the-lake swim and the opening of now iconic attractions receive special attention, as do the

popularity of western themed dude ranches and the pervasive influence of the automobile on tourism and popular culture.

Throughout the summer, guest speakers will present engaging programs that delve into several of the exhibition’s themes. “Welcome to Lake George: Vacation Paradise of the ’50s and ’60s,” was organized by the museum’s vice-president, Lisa H. Hall, publisher of the Lake George Mirror.

According to Hall, she drew upon the resort newspaper’s archives to help inform and illustrate the exhibits. “During the ‘50s and ‘60s, the Lake George Mirror chronicled the changes on Lake George – the decline of the great resort hotels, he destruction of the mansions along Lake Shore Drive, and the proliferation of motels and

According to Hall, she drew upon the resort newspaper’s archives to help inform and illustrate the exhibits. “During the ‘50s and ‘60s, the Lake George Mirror chronicled the changes on Lake George – the decline of the great resort hotels, he destruction of the mansions along Lake Shore Drive, and the proliferation of motels and

tourist cabins.

“It also promoted the attractions, the restaurants and resorts and championed projects such as the Million Dollar Beach, the Northway, the Prospect Mountain Highway and

the expansion of Shepard Park. It was the lake’s newspaper of record,” said Hall.

Artifacts on display include many on loan from its president, Henry Caldwell, owner of Black Bass Antiques. “The ‘50s and ‘60s were a great time on Lake George, and many people who come into my shop have wonderful memories of the theme parks and the mom-and-pop resorts. The artifacts from my shop embody that special time,” said Caldwell.

The exhibition is enhanced by objects from the Bolton Historical Museum’s own collections and by loans from local residents. “The exhibition draws from an extensive collection of vintage advertising, promotional materials, and memorabilia that highlight the allure of Lake George in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

“Visitors will be transported to a time when the region was a premier getaway for families, socialites, and vacationers seeking fun, glamour, and relaxation,” said Dr. Glenn Long, the museum’s executive director.

Located at 4924 Lakeshore Drive, with an entrance in Rogers Park, The Bolton Historical Museum is open seven days a week, 10 am to 4 pm, from Memorial Day through Columbus Day.

A version of this article first appeared on the Lake George Mirror, America’s oldest resort paper, covering Lake George and its surrounding environs. You can subscribe to the Mirror HERE.

Illustrations, from above: The King George Motel in Lake George, ca. 1950s; Porter’s Cottages, built by Earl Woodwar in Lake George, ca. 1950s; Square dancing at Frontier Village in Lake George, ca. 1960s; Lake George Steamboat Company’s Mohican in Paradise Bay, ca. 1960s postcard; The Surfside Mote in Lake George, ca. 1950s; and the interior of The Bolton Historical Museum.

Source link