Katherine Anne Porter: Saratoga County’s Pulitzer Prize Winner

Saratoga County, NY has attracted more than its share of literary lights, whether they have spent time at the Yaddo retreat or taken in “health, history and horses.” One of these writing notables is a point of pride for residents of the town of Malta.

Saratoga County, NY has attracted more than its share of literary lights, whether they have spent time at the Yaddo retreat or taken in “health, history and horses.” One of these writing notables is a point of pride for residents of the town of Malta.

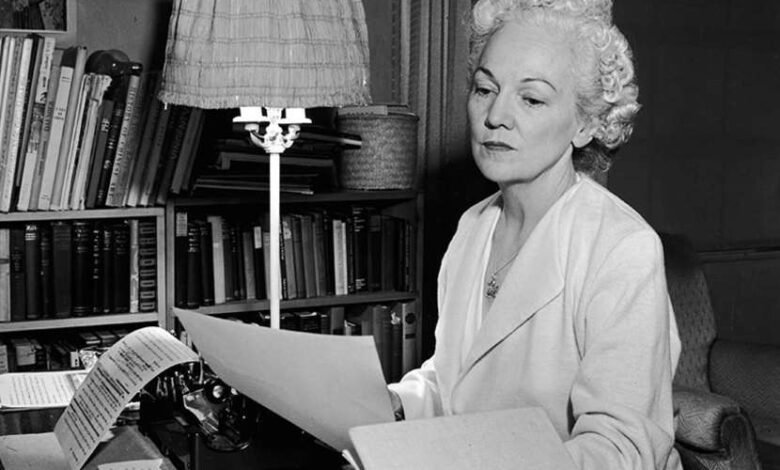

Katherine Anne Porter, a recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, lived in Malta and owned a home there.

Porter is perhaps best known for having written Ship of Fools, the 1962 novel that was the basis for the 1965 movie of the same name. Porter received the Pulitzer for the publishing in 1965 of The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter, a volume of her short stories she had published up to that point.

Three of those stories were also published together in a separate volume in 1937 called Pale Horse, Pale Rider.

The real life of Katherine Anne Porter could have easily described some colorful characters in her well-crafted stories. She was born Callie Russell Porter on May 15, 1890, the fourth of five children of a struggling farmer, in the dusty small town of Indian Creek, Texas.

Her mother died when Callie was two, so her father, Harrison, moved the family to Kyle, Texas, a more substantial community (and the “pie capital of Texas”) just outside Austin.

Callie’s grandmother, Catharine Ann Porter (note the spelling), helped raise the children. In tribute to her grandmother, Callie later changed her own name to Katherine Anne Porter.

After the family moved to several other cities, in Texas and Louisiana, Porter attended a private girls’ school in San Antonio. A bright youngster, she read widely and studied music, but was never educated beyond grammar school.

In 1906 at the age of 16, she married John Henry Koontz. Lasting nine years, it was the longest of her five marriages. Later in life, she half-jokingly said that she remembered only three of those unions.

In a review of a biography commissioned by Porter in her later years (Katherine Anne Porter, A Life by Joan Givner), literary critic Elizabeth Hardwick wrote of Porter: “She was beautiful, a spendthrift, an alert coquette and, since she lived long, a good many of her friends, lovers and three of her husbands were younger than she was.”

In 1915 Porter traveled to Chicago to try acting for a silent film company but soon became interested in journalism. Through the late ‘teens and 1920s she took writing jobs and did freelance work for magazines and newspapers.

In an era when women were becoming increasingly independent, she also began writing her own short stories and poems. One of her better short stories, “Flowering Judas,” was published in 1930.

Her writing yielded a $2,000 Guggenheim Fellowship, which she used in 1931 to travel by steamship from Mexico to study in Germany. On that voyage, aboard the S.S. Vera, she took notes about the wide variety of passengers she met. Porter’s notes laid the groundwork for the much later publication of Ship of Fools.

By 1939 she had gained a reputation as “one of the country’s best writers,” according to one sympathetic biographical sketch. This led to a stay during 1940 at Yaddo, the artists’ retreat in Saratoga Springs. Enter the town of Malta.

While at Yaddo, Porter and a companion took an auto ride one day in January 1941 through the rural area south of Saratoga Lake. On the ride, she spotted and fell in love with a two-story, seven-room country house on Malta’s Cramer Road. She soon bought it — what she called her “dream house” — for $2,000 (including a $200 down payment) and called it South Hill.

In a letter to her fifth husband, according to another biographer, Porter expressed “soulful feelings about how this special place [South Hill] would heal her hurts, inspire her creativity and ground her.” She got to work making needed repairs there.

However, the task of home rehabilitation, cold upstate winters and the social isolation of World War Two (despite parties she hosted there for Truman Capote, Eudora Welty and others) eventually became too much for Porter.

However, the task of home rehabilitation, cold upstate winters and the social isolation of World War Two (despite parties she hosted there for Truman Capote, Eudora Welty and others) eventually became too much for Porter.

In 1946 she sold South Hill to George F. Willison, a writer and editor known for producing several nonfiction volumes on American history. Willison later became a speechwriter for U.S. Sen. Estes Kefauver and New York Governor Averill Harriman.

Over the years, the South Hill house on Cramer Road has been maintained in excellent condition by subsequent owners, and there is now a roadside historical marker near the house.

Throughout the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, Porter remained active writing stories, teaching, lecturing, and making public appearances. A Ford Foundation grant in 1959 spurred her to complete her long-delayed novel Ship of Fools.

The novel had remained dormant until 1940, when she started writing the book using her notes from the Vera voyage. But it wasn’t published until 1962, when she was 72.

When asked to explain why the publisher (Little, Brown & Co.) kept announcing, then delaying the book’s release, Porter replied, in character, “Look here, this is my life and my work and you keep out of it. When I have a book I will be glad to have it published.”

When it finally appeared, the novel received good reviews and was the best-selling fiction title of 1962. Years later in The New Yorker, the critic Hilton Als wrote that Ship of Fools is “a thick book remarkable for its concision — the many plot points move along at a good clip — [it] is less a masterwork than a piece of cinema, a detailed script about the lost and the damned and the tragedy of history that no man can escape.”

And it did become cinema. Hollywood paid Porter $400,000 for the movie rights (equivalent to about $4 million today), and Stanley Kramer produced and directed. Notable stars included Vivian Leigh (in her last film role), Simone Signoret, Oskar Werner, George Segal and Lee Marvin.

Released in 1965, the movie won two Oscars (art direction and cinematography). Notably, the movie was banned in Spain by that country’s dictator, Francisco Franco, due to its anti-fascism.

Porter achieved the pinnacle of the literary world in 1965, when her The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter received the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. These works of the 1960s yielded for Porter several honorary degrees, long-sought financial security and even invitations to events at the White House.

The last 10 years of Porter’s long life were marked by declining health but also by a couple of unusual projects.

In one, she sought to write an essay for Playboy magazine on the Apollo 17 moon landing, but that was never finished.

In 1977, she published The Never-Ending Wrong, a book about the Sacco-Vanzetti trial and execution. After suffering several disabling strokes in 1977, Porter died on September 18, 1980, in her 90th year.

Tom Williams is town historian for the town of Malta. A graduate of the University of Rochester, he is a retired journalist, having worked as a reporter and editor for daily and weekly newspapers, and for national trade magazines. Beth Alvarez of the Katherine Anne Porter Society at the University of Maryland assisted with research for this article.

Illustrations, from above: Katherine Anne Porter at work in 1947; and the house Porter lived in in Malta.

Source link