John Langdon Sullivan & Hudson River Steam Tow Passage Boats, 1825

The following article by engineer John Langdon Sullivan was published in the Commercial Advertiser on June 25, 1825. Sullivan was an inventor of one of the first steam-powered towboats which operated on the route of the Middlesex Canal (completed in 1803, between the Merrimack River and Boston). Having established the Boston Steamboat Company in 1818, he secured permission from the New York State Legislature to operate barges towed by steamboats on the Hudson River, but was stymied by the monopoly on steam navigation Robert Livingston and Robert Fulton had secured for themselves. Here he argues that towed passenger boats would be safer and he should be allowed to proceed. You can learn more about Sullivan and his tow-boat experiments below the article.

The following article by engineer John Langdon Sullivan was published in the Commercial Advertiser on June 25, 1825. Sullivan was an inventor of one of the first steam-powered towboats which operated on the route of the Middlesex Canal (completed in 1803, between the Merrimack River and Boston). Having established the Boston Steamboat Company in 1818, he secured permission from the New York State Legislature to operate barges towed by steamboats on the Hudson River, but was stymied by the monopoly on steam navigation Robert Livingston and Robert Fulton had secured for themselves. Here he argues that towed passenger boats would be safer and he should be allowed to proceed. You can learn more about Sullivan and his tow-boat experiments below the article.

The expediency and humanity of separating passengers from the danger of steam-boat explosions may now again be urged upon the attention of this community. To become habituated to danger, is not to remove it from the path so many must travel. Time wears upon the steamboats in use, and constantly increases their liability to accident. None now-a-days take passage without a consciousness of hazard.

Formerly, the deck was a scene of remarkable cheerfulness – it has become a place of anxiety. The occurrence of the least noise alarms – the awful hissing of the steam from the safety valve, no longer gives assurance of safety, but rather bears testimony to the existence of a tremendous force, which even that precaution cannot always guard against.

So many have now been the explosions fatal to not a few, and dangerous to great numbers, that friends part at a steam-boat never without a feeling of the possibility of a catastrophe, from past example, too horrible for description.

Nor has the occurrence of accident been peculiar to our own country and navigation. We know that they have happened at manufactories as well as on board vessels, in various places in England, at Pittsburg and Philadelphia, on the Ohio, the Mississippi the Santee and the Hudson.

The explosion of boilers depends on several causes; and some of them are scarcely known to that class of men to whom the management of the engine is committed. It is a poor consolation to the bereaved, and the scalded, that the testimony of the captain and crew, on oath proves that they have not been careless – that the water, and the steam, was in due order and degree – that a “vacuum in a flue” (if this were possible) might have been the cause, or else some defect of workmanship.

The persons employed about a steam-boat may not be aware that the force of steam accumulates in a geometrical ratio to the arithmetical increase of the fire – that the sheets of metal of which the boiler is made, are undergoing an external oxidation from the action of heat, and this with rapidity, if the boiler gets foul within.

The same effect takes place on the flues; and a little negligence of the supply, allows the water to leave them uncovered, when they soon become red hot – and if they do not give way at once, their heated surface may, on the sudden accession of the water, generate the steam too fast for the safety-valve to vent: or if the valves of the supply-pump get choked, or out of order, and the constant entrance of water fails, in a short time the flues, and even the bottom of the boiler, becomes red hot – and some portion of the water and steam within, is probably decomposed into its constituents, oxygen and hydrogen gas, which, igniting, from the heated iron, produces those tremendous effects, which, igniting, from the heated iron, produces those tremendous effects, which have been witnessed in a few instances out of the many less violent, but not less fatal to life, in England – in the ferryboat at Powles Hook, and at Pittsburg: and these were engines of low pressure.

Experience has shewn, that no kind of steam-engine is exempt from danger. But the danger is increased on our waters by flued-boilers. The flues pass through the water: the pressure is on their convexity: their strength is not within any rule of computation. On the contrary, those boilers which are single cylinders, have the pressure on the concave side, and are within certain established rules of strength. But this kind of boiler must necessarily be so set, as unavoidably to heat the boat too much to be tolerable to passengers.

There is not therefore a steam-boat on the waters of New-York which has not a flued-boiler. That inconvenience is nothing to the crew of the boat, as she may be well ventilated; and, if necessary, the lodgings be on deck.

The single boiler is safer for them, too, as one only of the number used, can give way at once. The power that may be thus put on board a steam-tow-boat may be so great, as to produce a speed heretofore unknown, and may be expected to accomplish the passage between New-York and Albany, between sun-rise and sun-set.

The deck for the light passage boat in tow will be free from all encumbrance and inconvenience – heat, smoke, effluvia, noise and danger; uniting convenience and elegance with safety and speed. Those whose interest is averse to that of the public, may say this is no improvement in steam navigation.

I am willing to have this point decided by the public. Test the opinion by opportunity of choice, and we shall see no ladies on board of any other than the towed passage boat – no parent – no man of reflection – that will not be willing to pay a little more for a pleasant, secure, and not inelegant mode of conveyance.

It required no peculiar discernment to foresee the increase of the danger in steam-boats, especially when competition should reduce the fare so low as to induce the employment of the cheapest means of operation. The remedy is alone the separation of the load from the power.

It was under a strong impression that this separation has utility, and would become an acknowledged improvement, that my experiments were made, (with an engine of twenty horse power) which led to the grant of my patent, founded on one of the principles of the Patent law, the application of a known power to a new and useful purpose.

And I consider it a fair and convincing testimonial of its utility, to mention, on all proper occasions, that it had not escaped the discernment of Mr. Fulton.

He is well known to have opposed my claim, with a claim of his own per the same improvement: yet the arbitrators, between us unanimously awarded the priority to me.

He had not become by experiment, as I had, aware of the little loss of speed in towing, nor of the diminished resistance to a boat following in the wake of the power boat: the former applicable to freight boats along-side, the latter to the passage boat.

As to the points of expense and speed, there are circumstances favorable to the new system. The single, or old form of steam navigation, requires the whole weight of the machinery to be at or near the center of a long hull, which, to be sufficiently strong, must be heavy timbered.

She, therefore, draws and displaces more water, and meets with more resistance. But on the new system, we may have a comparatively light power boat, and a very light passage boat. The power may be greater than usual, the resistance less.

My patent bears date the 4th of December, 1816, of which I annex a copy; and of course there remains but a few years of the term. But it may be renewed. Every proper step was taken to obtain admission into the waters of New-York, closed and exclusively occupied by the State’s grant to Messrs. [Robert] Livingston and Fulton, lately decided to be unconstitutional.

Congress may therefore renew my patent for such term of time as may appear to that honorable body, under all circumstances, to be just and consistent with the public good; not only because those of Evans and of Whittemore were renewed, but because the intention of the provisions of law were frustrated in my case; and because it is good policy in a government to induce capitalists, by the temporary privilege of a patent, to establish in use any costly improvement that may thereafter, by example and experience, become of great and lasting public benefit.

[The writer refers here to the work of Oliver Evans (1755-1819), one of the first Americans to build steam engines and an advocate of high-pressure steam (as opposed to low-pressure steam); and also Amos Whittemore (1759-1828), an inventor of a wool and cotton carding machines.]Nor are patentees without protection. They have been put by a law of Congress (Feb. 1819) expressly under the protection of the Circuit Court of the United States, and may file a bill, and by injunction of court obtained, prevent the infringement of a right from proceeding a second step. Nor is he precluded by the process from the recovery of treble damages given by the previous provisions of law.

[In 1819, Congress expanded the jurisdiction of the U.S. circuit courts to include all cases arising under federal patent laws. This expansion built on the Patent Act of 1793, which had already granted patent holders the right to bring infringement suits in these courts.]The recent explosions on board the Legislator and the Constitution, ought, perhaps to revive the recollection of others, and to convince the community that there can be no assurance of safety but by the separation of the accommodation from the power.

[On June 2, 1825, the Legislator exploded while building up steam at its dock in New Brunswick, New Jersey, killing four people. One of the Constitution‘s two boilers exploded near Poughkeepsie on June 20, 1825 with 80 passengers onboard; two member of the crew were scalded to death.]This city – or those of the inhabitants who feel the force of those considerations, which speak loudly to the heart, the friends – the philanthropic and the wealthy should not, perhaps, wait till some crowded steam-boat, shall be destroyed with all on board.

[Indeed, on April 27, 1865, the Sultana, carrying over 2,300 passengers (mostly Union soldiers) exploded on the Mississippi River near Memphis, killing 1,864 people – it remains the largest maritime disaster in American history.]If it were not my right and interest to invite to this branch of enterprise, I should do so from a sense of duty, knowing so well the causes of the explosion of boilers, I therefore take this method to invite the formation of a powerful but not numerous company, to carry on this branch of steam navigation upon the waters of New-York.

Should this proposition be acceptable, I shall hope it may be communicated before my professional employments shall make it less convenient than at this moment, to make the proper arrangements.

[Signed] JNO. L. SULLIVAN, Civil Engineer, State-street, No. 1, June 22, 1825.

Words of the Patent referred to in the preceding publication:

“I claim, as my invention, the application of steam-engine power, placed in one vessel, to the towing or drawing after her another vessel, for the purpose of conveying thereon passengers of merchanidize, or either of them, being a new application of a known power.

“The manner in which this application may be made varies with the circumstances in some measure, but essentially consists in attaching the packet to the steam-boat, with ropes, chains or spars, so as to communicate the power of the engine, from the towing vessel to the other vessel, thus kept always at a convenient distance apart, & c.” The advantages & c. are then described.

John L. Sullivan & Hudson River Towboats

John Langdon Sullivan (1777–1865), a civil engineer, inventor, and physician, was born in Saco, Massachusetts (now in Maine), and initially made his living as a merchant in Boston.

His father was James Sullivan, an attorney and Governor of Massachusetts (1807-1808), who was the principal promoter and investor of the Middlesex Canal, begun in 1793. His uncle was General John Sullivan, of Sullivan – Clinton Expedition fame.

John L. Sullivan traveled from Boston to England and France, where he studied modern canal-building techniques. In 1804 (or 1808, sources differ) he became an agent and engineer of the Middlesex Canal, serving as a kind of CEO for the Middlesex Canal Company which operated the canal.

He joined the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1810 and according to historian William E. Gerber:

“In 1811 he delivered a paper in which he described practical means for conducting commerce by canal across New York state, and of opening up the midwest to commerce transported across the Great Lakes on boats powered by steam engines.”

That same year the Massachusetts Legislature created an incorporated company with an “Act to incorporate John L. Sullivan and others, by the name and style of The Merimack Boating Company.”

Sullivan’s inventive work was interrupted while he served as a lieutenant in the Boston militia during the War of 1812. In 1814, however, he patented a “steam tow-boat” and other shipbuilding improvements in 1817–18. In 1817 he wrote to Thomas Jefferson:

“While at work on the river, I tried many experiments with a Steam boat of twenty horse power, in towing loaded boats upstream, conceiving that this power might be applied so as to require but a small draft of water, and that some advantage was to be gained from the reaction of the broken water or wake behind the preceding boats.

“I was not disappointed in this expectation finding that while the steam boat was going at the rate of three miles an hour, with two boats loaded in tow, a man could draw those in tow up to the steam boat, and hold them there, while it would have required two horses to have carried them as fast separately.”

In February 1820, Sullivan reported about the usefulness of these towboats on eastern rivers:

“In the freshets, and generally, the steam towing boat has been very useful, being able to take two loaded boats against the current when they could not have moved at all – at other times carrying them in half a day as far as they would have gone in two by the ordinary means . This boat has served to prove the practicability… through [New Hampshire and Vermont].”

Sullivan was an engineer for the National Board of Internal Improvements in 1824–25, a federal agency created under the Whigs’ “American System” to oversee and facilitate construction of infrastructure projects.

Apparently failing to secure his steam towing operation in New York, during the 1830s Sullivan changed careers, getting a medical degree from Yale University in 1837. He moved to the city of New York in the 1840s and practiced homeopathic medicine for more than two decades before his death in 1865.

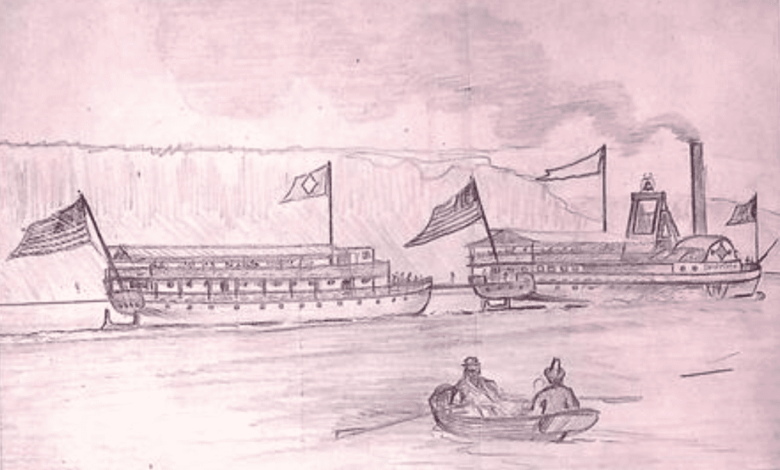

Sullivan’s steamboat tows did come to the Hudson River. In 1824-25 William C. Redfield built the Commerce and Swiftsure for Abraham Van Santvoord‘s Steam Navigation Company to tow passenger barges and freight vessels. These were the primary tow boats in operation on the Hudson until 1839.

In 1868, thee Troy Daily Whig reported that:

“On three or four occasions, after serious accidents had occurred, the entire travel traffic forsook the steamboats, and took to the sloops and stages again. It was in one of these dilemmas that the steamboat men hit upon the plan of fitting up passage boats in good style and with all steamboat conveniences and requisites, except steam boilers.

“These boats were towed by the steamers, those frightful affairs being placed some seventy five yards ahead, connected with the passage boat by a line. This was the very first “towing” done on the Hudson River. The system survived some years, until public confidence in the safety of steam-boat traveling was restored.”

This article above was located by Hudson River Maritime Museum volunteer researcher George A. Thompson and annotated by John Warren, who also added the details about Sullivan’s life.

Illustration, the steamer Swiftsure tows a “safety barge” on the Hudson River between New York and Albany, ca. 1835 – note the platform between boats which allowed passengers to travel between the two. From Samuel Ward Stanton’s Hudson River Steamboats: The Flyers of the Hudson (1965).

Read more about steamboats in New York.

Source link