‘Hybrid’ skull may have been a child of Neanderthal and Homo sapiens

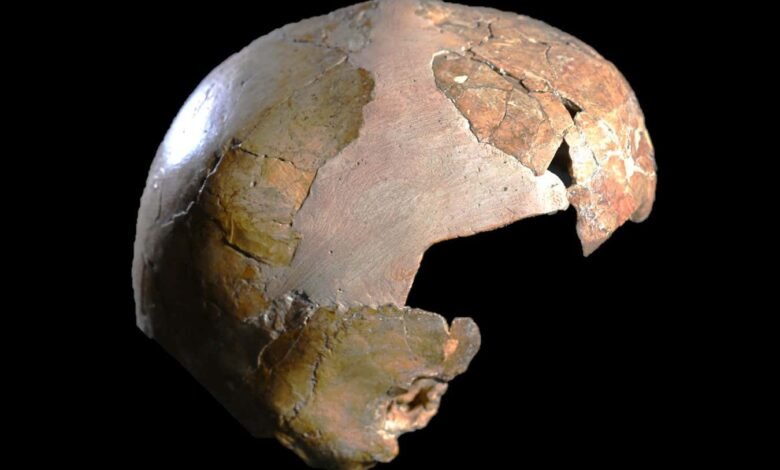

The cranium of a girl thought to be the offspring of Neanderthal and Homo sapiens parents

Israel Hershkovitz

A 140,000-year-old hominin skull from Israel probably belonged to a hybrid child of Neanderthal and Homo sapiens parents, according to an analysis of its anatomy. The 5-year-old girl was buried within the earliest known cemetery, possibly reshaping what we know about the first organised burials and the humans behind them.

The skull was originally unearthed from Skhul Cave on Mount Carmel in 1929. In total, these early excavations uncovered seven adults, three children and an assortment of bones that belonged to 16 hominins – all later assigned to Homo sapiens.

The classification of the child’s skull, however, has been contested for nearly a century, partly because the jaw looks dissimilar to typical Homo sapiens mandibles. Original work hypothesised that it belonged to a transitional hominin called Paleoanthropus palestinensis, but later research concluded it most likely belonged to Homo sapiens.

Anne Dambricourt Malassé at the Institute of Human Paleontology in France and her colleagues have now used CT scanning on the skull and compared it with other known Neanderthal children.

“This study is maybe the first that has put the Skhul child’s remains on a scientific basis,” says John Hawks at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who wasn’t involved in the new research. “The old reconstruction and associated work, literally set in plaster, did not really enable anyone to compare this child with a broader array of recent children to understand its biology.”

Malassé and her colleagues found the mandible had distinct Neanderthal characteristics, while the rest of the skull was anatomically consistent with Homo sapiens. They conclude that this combination of features suggests that the child was a hybrid whose parents were different species.

“I have long thought that hybridisations were not viable and I continue to think that they were mostly abortive,” says Malassé. “This skeleton reveals that they were nevertheless possible, even though this little girl lived only 5 years.”

While the new work significantly advances our understanding of the important Skhul child skull, we can’t definitively identify the child as a hybrid without extracting its DNA, which researchers have not been able to do, says Hawks. “Human populations are variable and there can be a lot of variability in their appearance and physical form even without mixing with ancient groups like Neanderthals,” he says.

We know from analyses of ancient and modern genomes that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals have swapped genes many times during the past 200,000 years. In 2018, a 90,000-year-old bone fragment found in Russia was identified as a hybrid between Neanderthals and Denisovans, another ancient hominin, using DNA analysis.

The Levant may have been a particularly important region for mixing among hominin species, due to its position between Africa, Asia and Europe. The region has been characterised as a “central bus station” for humans living in the Pleistocene, says Dany Coutinho Nogueria at the University of Coimbra in Portugal.

The new study forces us to call into question the attribution of the earliest grave site to Homo sapiens, says Malassé. This ritualised behavior may have come from Neanderthals, Homo sapiens or interactions between the two.

“We do not know who buried this child, whether this place chosen to bury the corpse was that of a single community, or whether communities from different lineages, but which coexisted and established contacts or even unions, shared rites and emotions,” says Malassé.

Topics:

Source link