Hudson River Defenses in the Revolutionary War

The Hudson River is not a place that’s conducive to a leisurely scuba dive. The water in the Hudson is very murky, cold, has uninviting currents, and ship traffic, so underwater archaeology in the Hudson River has mainly relied on remote sensing to image the river bottom.

The Hudson River is not a place that’s conducive to a leisurely scuba dive. The water in the Hudson is very murky, cold, has uninviting currents, and ship traffic, so underwater archaeology in the Hudson River has mainly relied on remote sensing to image the river bottom.

According to Dr. Daria Merwin, an underwater archaeologist by training and Co-Director of the Cultural Resource Survey Program at the New York State Museum, initial surveys have mapped roughly 300 anomalies that may represent historic shipwrecks and there are already a few known sites from the American Revolution in the Hudson River.

This spring, Dr. Merwin spoke at the New York State Museum about maritime military encounters against the all-powerful British Navy during the Revolutionary War. What follows is extracted from her talk, which you can find here in its entirety.

Contested Terrain

Like New York Harbor and Long Island, the Hudson River was a strategically important and heavily contested landscape from the opening battles of the American Revolution.

Like New York Harbor and Long Island, the Hudson River was a strategically important and heavily contested landscape from the opening battles of the American Revolution.

In an effort to control the river, in 1775 the Second Continental Congress ordered the construction of two forts in the Hudson Highlands, a natural choke point on the river. That same year the Continental Navy was born when a naval committee was authorized to purchase merchant ships and convert them into an emergency fleet.

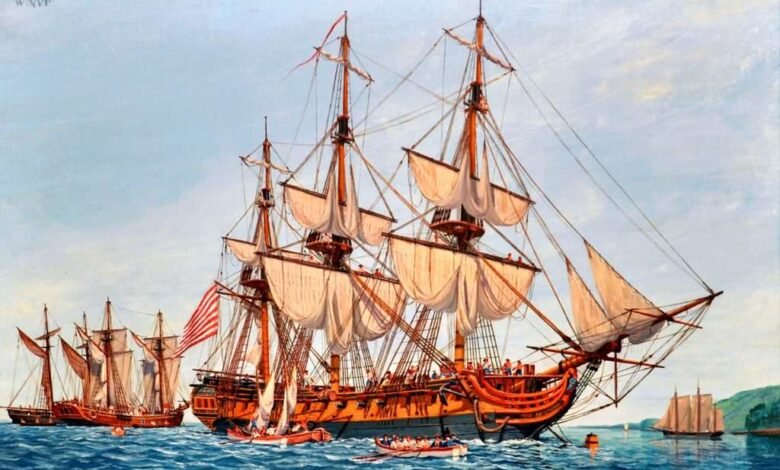

It was soon apparent that new warships would be required to face the British fleet so Congress ordered 13 frigates to be built. Two of these new warships were built in on the Hudson River in Poughkeepsie; the 28-gun Congress and 24-gun Montgomery, both launched in October of 1776, before they were fully completed.

At the same time, fortification of the river was underway in anticipation of the inevitable arrival of British warships. Eight outposts were established along the river, five in the Hudson Highlands.

Part of the Revolutionaries’ plans for holding the river consisted of creating obstructions to catch or slow British ships at key locations where they’d be vulnerable to cannon fire from nearby fortifications.

These defensive structures included scuttled ships some rigged with iron pikes projecting just below the water surface to snag passing vessels. Some structures extended from shore to shore across the river, including two massive iron chains, and a series of sunken caissons with projecting iron pikes (these were placed north of West Point).

One of the most important naval innovations of the late 18th century was an invention of a torpedo carrying one-man submarine, The Turtle. This first submarine ever to have been used in combat was launched in New York Harbor in September 1776 on a mission to destroy the 64-gun HMS Eagle by planting an explosive device on the hull of the British ship.

One of the most important naval innovations of the late 18th century was an invention of a torpedo carrying one-man submarine, The Turtle. This first submarine ever to have been used in combat was launched in New York Harbor in September 1776 on a mission to destroy the 64-gun HMS Eagle by planting an explosive device on the hull of the British ship.

The pilot wasn’t able to place the bomb on the Eagle but instead released it into the water and that did result in a large explosion, although The Turtle failed to destroy its target. The British responded to this new threat by moving the fleet farther out to sea.

Despite the Revolutionaries’ efforts to hold the Hudson River, it fell to the British early in the war, in the occupation of the city of New York and New York Harbor after the Battle of Long Island (Battle of Brooklyn) in August, 1776.

The British Move Up The Hudson

After the Battle of Long Island the British ships Phoenix and Rose moved-up into the lower Hudson Valley. A futile attempt by seriously outgunned Americans to engage the British ships near Yonkers resulted in the loss of two American sloops (one of which may have been carrying The Turtle) and a British sailing tender.

In October of 1777 Fort Montgomery and Fort Clinton were attacked by British forces composed of more than 3,000 men and six ships. The Revolutionaries consisted of only about 900 men and five vessels.

These included the frigates Montgomery and Congress, which had been built in Poughkeepsie, two rowed galleys and a privateer sloop. In only two days the British gained control of both forts after attacking by land rather than by water as anticipated. The two Continental frigates and the galley Shark were burned to prevent their capture by the British.

Following the battle, the British fleet sailed north to Kingston to burn that city and the “fleet prison” located there by the New York Council of Safety. Known American losses in the Hudson River include:

At least eight “wood hulks” fitted with iron pikes as defensive obstructions at Fort Washington, August-October 1776;

Two sloops near Yonkers, August 16, 1776;

Montgomery, a 24-gun frigate, burned near Fort Montgomery, October 6, 1777;

Congress, a 28-gun frigate, burned on flats near Constitution Island, October 7, 1777;

Turtle, the submarine that may have been destroyed near Fort Washington, October 9, 1776;

Shark, an armed galley, burned near Constitution Island, October 10, 1777; and

Several “wood hulks” from the “fleet prison” near Rondout Creek, Kingston, burned October 1777.

The British are known to have lost just two vessels: Charlotta, a sailing tender, near Yonkers on August 16; and Mercury, a 20-gun frigate, lost near Manhattan on December 24, 1777.

Additionally, the river holds the remains of at least three defensive structures: a 1777 chain across the river at Fort Montgomery; a Chevaux de Frise at Pollepel Island; and the 1778 Great Iron Chain at West Point.

While the Patriot attempts to keep control of the Hudson River were ultimately unsuccessful, innovations first employed here and later refined by the fledgling American Navy, would factor into the rise of American sea power during the 19th century.

Recently an underwater archaeological survey attempted to locate Revolutionary War vessels and defensive structures in river between Fort Montgomery and West Point. The project entailed new high resolution sidescan sonar mapping of the entire river bottom in the study area along with multi-beam sonar work at dozens of

selected sites along with some metal detecting or magnetometer surveying.

Most of this work was conducted aboard the NOAA hydrographic survey vessel Rude (S 590) with additional ultra high resolution multi-beam data collection using other smaller vessels.

The survey has yet to definitively identify any of the watercraft lost during the Revolution. It’s possible that sedimentation in this portion of the river maybe have buried any remains. Some of the anomalies in the sonar data may represent buried shipwreck sites.

There has been positive identification of the Chevaux de Frise. These log obstructions, about six feet tall, were put on the river when the river was iced over in the winter and then filled with rocks. They would sink in the spring when the ice thawed.

There has been positive identification of the Chevaux de Frise. These log obstructions, about six feet tall, were put on the river when the river was iced over in the winter and then filled with rocks. They would sink in the spring when the ice thawed.

The British had enough loyalist supporters in the area watching and reporting what the Americans were doing however, and the British sailed passed them without incident.

Not all shipwrecks are found underwater. On July 13th 2010 mechanical excavators working adjacent to the south side of the World Trade Center foundations in lower Manhattan uncovered the remains of a hull of a vessel buried 20 to 30 feet below street grade.

Archaeologists monitoring the construction work saw uncovered timbers and stopped work at the site to assess the discovery. The New York State Historic Preservation Office determined the find was significant and directed archaeologists to form an appropriate team and excavate the site in a rapid but controlled manner.

The excavation yielded the partial remains of an almost completely iron-fastened ship with the preserved part measuring roughly 30-feet long by 15-feet wide there were also thousands of small artifacts some of which were directly associated with the ship and the rest related to land-filling after the ship was abandoned.

This is not the first time that ships have been found being used to support land-filling; it’s not even the first one in lower Manhattan. (In 1982 a large 18th-century merchant ship was unearthed 21-feet below 175 Water Street.)

This is not the first time that ships have been found being used to support land-filling; it’s not even the first one in lower Manhattan. (In 1982 a large 18th-century merchant ship was unearthed 21-feet below 175 Water Street.)

After in place documentation that included three-dimensional laser scanning, the whole structure was disassembled and the component parts wrapped and shipped to a conservation laboratory for wet storage, further documentation and assessment.

Tree ring dating indicates that the white oak used to construct the vessel was felled around 1773. Comparison with timbers from Independence Hall pointed to the origin in the Philadelphia area. Research suggests the gunship may have seen action during the American Revolution.

It was recently reconstructed and installed at the New York State Museum.

Read more about New York’s maritime history.

Illustrations, from above: A painting of the frigate USS Confederacy by William Nowland Van Powell, built in 1778 in Chatham, CT, and later captured and broken up by the British (courtesy Navy Art Gallery, Washington Navy Yard); detail from an 1784 map of Hudson River showing Fort Montgomery; Turtle model at the Royal Navy Submarine Museum; NOAA’s hydrographic survey vessel Rude; 1777 map detail showing the cheval-de-frise between Fort Lee and Fort Washington; and the discovery of the gunboat at the construction site for the Vehicular Security Center in Lower Manhattan, 2010 (courtesy AKRF).

Source link