How Oskar Schindler saved 1,200 Jewish people during World War Two

Alamy

AlamyThe Nazis carried out the final “liquidation” of the Kraków Jewish ghetto on 13 March 1943, an act of violence that shocked a factory owner into becoming a saviour. These events were depicted in Thomas Keneally’s novel Schindler’s Ark and Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List. But in 1982, Keneally told the BBC that Oskar Schindler’s story was handed to him during a chance meeting with a luggage salesman.

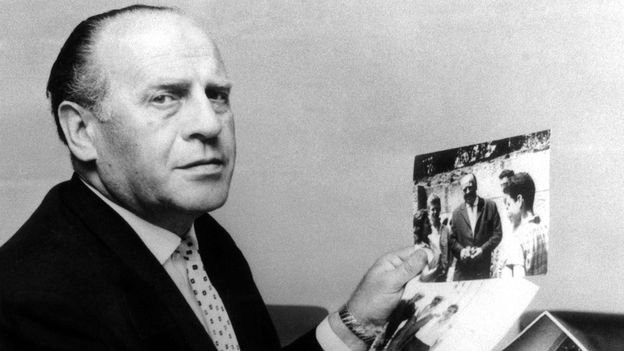

Oskar Schindler was living in relative obscurity when his story was first featured on the BBC in 1964. Journalist Magnus Magnusson told viewers of the current affairs programme, Tonight: “You may not have heard of him yet, but one day you will. Today, he lives in Germany; sick, unemployable and penniless. In fact, he lives on charity, but not the poor-box kind. The money that keeps him and his family alive comes from the 1,300 Jews whose lives he personally saved in the last war. Many of them are pledged to give one day’s pay a year to the man they call the Scarlet Pimpernel of the concentration camps.”

Schindler was in the news that day because it had been announced that a Hollywood film called To the Last Hour was to be made about his life. It came about because a few years earlier, Holocaust survivor Poldek Pfefferberg had shared with MGM producer Martin Gosch the almost preposterous story of how he was among thousands saved by a Nazi war profiteer: a handsome, womanising drunk and wheeler-dealer from Czechoslovakia who had previously demonstrated few heroic qualities. While that particular film would get stuck permanently in development hell, in 1980 Pfefferberg had a chance meeting with an unsuspecting Australian writer that would change both their lives.

Thomas Keneally was killing time at the end of a Los Angeles promotional trip (“I was being put up in unaccustomed grandeur by my publishers at a big hotel in Beverly Hills”) and window-shopping for a new briefcase before returning home to Sydney. He told the BBC’s Desert Island Discs in 1983 that the leather goods shop owner, “being a good central European,” came out to greet him and give him the hard sell.

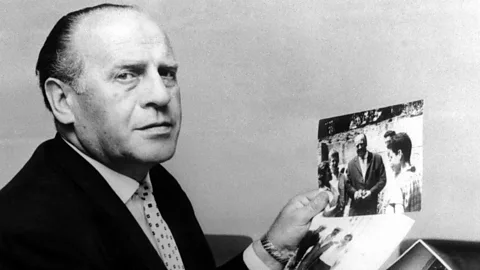

Keneally said: “[Pfefferberg] did produce a very good briefcase, and while I was waiting for the charges to be cleared on my credit cards – they’re very slow to clear Australian credit cards, I’ve noticed; it’s the convict reputation – he began to talk to me about his wartime experience.

“He knew I was a writer, and he said, ‘I’ve got a book for you. I was saved, but so was my wife, saved from Auschwitz by an extraordinary German, a big handsome Hitlerite dream of a man called Oskar Schindler. I have many Oskar Schindler documents. In the 1960s, a movie was nearly made about Oskar, and while we’re waiting for your credit card to be cleared, have a look at this material.’

Alamy

Alamy“He told his son to mind the shop, and he took me up to the bank on the corner, open on Saturdays. He talked them into running off photocopies of all this remarkable material, and at once I understood that here was a most astounding European character.”

One of those documents was what would become known as Schindler’s list. “The list is life,” Keneally would go on to write in his best-selling novel Schindler’s Ark, and “all around its cramped margins lies the gulf”.

From opportunist to saviour

Pfefferberg was born into a Jewish family in Kraków, where he had worked as a high school teacher and physical education professor until 1939, when Germany invaded Poland. He joined the Polish army and was wounded in battle. He told Keneally that when Poland fell to the Nazis and was partitioned between Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union, he had to make a tough decision: “We officers had to decide to go east or west. I decided not to go east, even though I was Jewish. If I had, I would have been shot with all the other poor sons of bitch in Katyn Forest.” He was imprisoned in the Kraków ghetto, a segregated area established in 1941 by the Nazis. About 15,000 Jewish people were herded into an area that previously housed about 3,000 residents, and forced to live in dehumanising conditions.

It was also in Kraków that the Nazi Party member Oskar Schindler was exploiting wartime misery for money, taking over several confiscated Jewish-owned businesses including an enamelware factory. At first, most of Schindler’s workers were non-Jewish Poles, but he later began to employ Jewish forced labourers from the ghetto. Pfefferberg became one of his employees. Meanwhile, the Nazis began rounding up groups of Jewish people at gunpoint and deporting them to nearby concentration camps. For those left behind, it was a time of terror.

Schindler was forever changed in March 1943 by the brutality of the Nazis’ final “liquidation” of the Kraków ghetto. Those deemed able to work were transported to the nearby Płaszów labour camp. Thousands more who were considered unfit for work were either murdered in the streets or sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. To save his workers from the camps, Schindler turned to using his talent for corruption and deceit. He continued to persuade Nazi officials that his workers were vital to the German war effort, bribing high-ranking SS officers with money and alcohol. His factory also produced ammunition shells to ensure it was regarded as a vital resource, and he listed the names, birthdates and skills of his Jewish workers, emphasising their importance to the Nazi war machine.

Keneally told the BBC: “What he virtually did was set up a benign concentration camp, not once but twice, and he kept on losing his people and getting them back by bribery, by bluff, by corrupting officials, and by exploiting the extraordinary SS bureaucracy that was involved in a preposterously systematic manner in the Holocaust.”

When the war ended, Schindler struggled with failed businesses and turned to alcohol. Those whom he had rescued would end up trying to rescue him, helping to support him financially. He died in 1974, aged 66. Survivors brought his remains to Israel, where he was buried in the Catholic Cemetery of Jerusalem. The inscription on his grave reads: “The unforgettable rescuer of 1,200 persecuted Jews.”

Among those saved were Pfefferberg and his wife Mila. After the war, the couple made their way to the US, and ended up in Beverly Hills. Pfefferberg sometimes went by the name Leopold Page. Keneally noted in his 2008 memoir Searching for Schindler that this was a name foisted on him upon arrival at Ellis Island in 1947. He told the BBC that writing this companion volume had been on his to-do list since Pfefferberg’s death in 2001. “I felt that, as big a character as Schindler was, the man who had brought me to him was also an extraordinary character,” he said.

An award-winning book and an award-winning film

When Steven Spielberg won the best director Oscar for Schindler’s List at the 1994 Academy Awards, in his speech he said: “This never could have gotten started without a survivor called Poldek Pfefferberg… All of us owe him such a debt. He has carried the story of Oskar Schindler to all of us.”

The film was based on Keneally’s novel, Schindler’s Ark, which won the UK’s prestigious Booker Prize in 1982. Some argued that it should not have been classified as fiction, as the author had applied imaginative literary techniques to real-life events in the manner of works such as Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff. Looking back in 2008, while discussing his Schindler memoir, Keneally told the BBC that the debate had been good for business. “These days archbishops don’t do writers the great benefit of banning them from the pulpit, but a literary controversy does nearly as well as the archbishops of the past did in promoting a book,” he said.

In his Booker Prize acceptance speech, Keneally thanked Pfefferberg and other survivors who helped him tell the story. He said: “I’m in the extraordinary position that’s akin to that of a Hollywood producer when he humbly accepts his Oscar, and thanks so many people. Normally a writer doesn’t have to thank so many people, but most of my characters are still alive. And I’d also like to remember the extraordinary character whom Oskar was.”

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

Source link