How Charles M Schulz created Charlie Brown and Snoopy

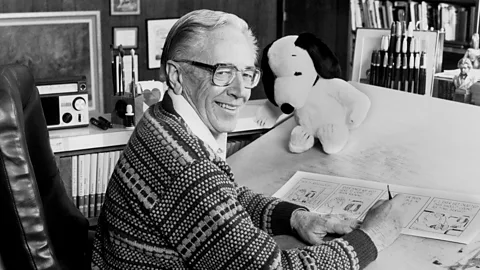

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCharles M Schulz drew his beloved Peanuts strip for 50 years until his announcement on 14 December 1999 that ill health was forcing him to retire. In History looks at how an unassuming cartoonist built a billion-dollar empire out of the lives of a group of children, a dog and a bird.

Charles M Schulz’s timeless creation Charlie Brown may have been as popular as any character in all of literature, but the cartoonist was modest about the scope of his miniature parables. In a 1977 BBC interview, he said: “I’m talking only about the minor everyday problems in life. Leo Tolstoy dealt with the major problems of the world. I’m only dealing with why we all have the feeling that people don’t like us.”

This did not mean that he felt as if he was dealing with trivial matters. He said: “I’m always very much offended when someone asks me, ‘Do I ever do satire on the social condition?’ Well, I do it almost every day. And they say, ‘Well, do you ever do political things?’ I say, ‘I do things which are more important than politics. I’m dealing with love and hate and mistrust and fear and insecurity.'”

While Charlie Brown may have been the eternal failure, the universal feelings that Schulz channelled helped make Peanuts a global success. Born in 1922, Schulz drew every single Peanuts strip himself from 1950 until his death in February 2000. It was so popular that Nasa named two of the modules in its May 1969 Apollo 10 lunar mission after Charlie Brown and Snoopy. The strip was syndicated in more than 2,600 newspapers worldwide, and inspired films, music and countless items of merchandise.

Part of its success, according to the writer Umberto Eco, was that it worked on different levels. He wrote: “Peanuts charms both sophisticated adults and children with equal intensity, as if each reader found there something for himself, and it is always the same thing, to be enjoyed in two different keys. Peanuts is thus a little human comedy for the innocent reader and for the sophisticated.”

Schulz’s initial reason for focusing on children in the strip was strictly commercial. In 1990, he told the BBC: “I always hate to say it, but I drew little kids because this is what sold. I wanted to draw something, I didn’t know what it was, but it just seemed as if whenever I drew children, these were the cartoons that editors seemed to like the best. And so, back in 1950, I mailed a batch of cartoons to New York City, to United Features Syndicate, and they said they liked them, and so ever since I’ve been drawing little kids.”

Of Snoopy and Charlie Brown, he said: “I’ve always been a little bit intrigued by the fact that dogs apparently tolerate the actions of the children with whom they are playing. It’s almost as if the dogs are smarter than the kids. I think also that the characters I have serve as a good outlet for any idea that I may come up with. I never think of an idea and then find that I have no way of using it. I can use any idea that I think of because I’ve got the right repertory company.”

Schulz called upon some of his earliest experiences as a shy child to create the strip. As a teenager, he studied drawing by correspondence course because he was too reticent to attend art school in person. Speaking in 1977, he said: “I couldn’t see myself sitting in a room where everyone else in the room could draw much better than I, and this way I was protected by drawing at home and simply mailing my drawings in and having them criticised. I wish I had a better education, but I think that my entire background made me well suited for what I do.

“If I could write better than I can, perhaps I would have tried to become a novelist, and I might have become a failure. If I could draw better than I can, I might have tried to become an illustrator or an artist and would have failed there, but my entire being seems to be just right for being a cartoonist.”

Never give up

Peanuts remained remarkably consistent despite the relentless publishing schedule, and Schulz would not let the expectations of his millions of fans become a distraction. He said: “You have to kind of bend over the drawing board, shut the world out and just draw something that you hope is funny. Cartooning is still drawing funny pictures, whether they’re just silly little things or rather meaningful political cartoons, but it’s still drawing something funny, and that’s all you should think about at that time – keep kind of a light feeling.

“I suppose when a composer is composing well, the music is coming faster than he can think of it, and when I have a good idea I can hardly get the words down fast enough. I’m afraid that they will leave me before I get them down on the paper. Sometimes my hand will literally shake with excitement as I’m drawing it because I’m having a good time. Unfortunately, this does not happen every day.”

Despite his modesty, Schulz insisted he was always confident that Peanuts would be a hit. He said: “I mean, when you sign up to play at Wimbledon, you expect to win. Obviously, there are a lot of things that I didn’t anticipate, like Snoopy’s going to the Moon and things like that, but I always had hopes it would become big.”

Schulz generally worked five weeks in advance. On 14 December 1999, fans were dismayed to learn that he would be hanging up his pen because he had cancer. He said that his cartoon for 3 January 2000 would be the final daily release. It would be followed on 13 February with the final strip for a Sunday newspaper. He died one day before that last strip ran.

In it, Schulz wrote: “I have been grateful over the years for the loyalty of our editors and the wonderful support and love expressed to me by fans of the comic strip. Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy… how can I ever forget them…”

Back in 1977, Schulz insisted that the cartoonist’s role was mostly to point out problems rather than trying to solve them, but there was one lesson that people could take from his work. He said: “I suppose one of the solutions is, as Charlie Brown, just to keep on trying. He never gives up. And if anybody should give up, he should.”

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

Source link