George Pratt, Lake George’s ‘Mohawk Warrior’ & Saratoga Springs

I was pleased to recently learn through the New York Almanack and Lake George Mirror about the planned restoration of historic sculptures at the Lake George Battlefield Park.

I was pleased to recently learn through the New York Almanack and Lake George Mirror about the planned restoration of historic sculptures at the Lake George Battlefield Park.

I have a special interest in the “Mohawk Warrior” sculpture produced by Alexander Phimister Proctor and the unique history surrounding this monumental work.

This sculpture was a gift from George D. Pratt, who commissioned the artist. Interestingly, the sculpture was conceived as a component of the planned conception for the New York State Reservation in Saratoga Springs (now known as Saratoga Spa State Park).

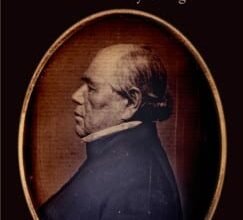

In Empire State terms, George Dupont Pratt was a “flat-lander,” having been born in Brooklyn in 1869. His father, Charles M. Pratt was a founder and director of the Standard Oil Company, having merged his Pratt Oil Works of Greenpoint into the burgeoning new firm.

In Empire State terms, George Dupont Pratt was a “flat-lander,” having been born in Brooklyn in 1869. His father, Charles M. Pratt was a founder and director of the Standard Oil Company, having merged his Pratt Oil Works of Greenpoint into the burgeoning new firm.

Charles and his wife Mary Helen instilled the appreciation of education and the arts in their eight children, and founded the Pratt Institute. At the time of his 1891 death, the New York Times described Charles Pratt as “probably the wealthiest man in Brooklyn.”

George Pratt was graduated from Amherst College in 1893, and despite his education and family wealth, began his professional career as a shop hand on the Long Island Railroad.

He learned all aspects of that business, even operating locomotives and ferry boats. He moved on to financial management in the new century, becoming part of Charles Pratt & Company, and vice-president at Pratt Institute, while traveling extensively pursuing photography and big game hunting.

During these travels he collected natural wonders, works of art and antique relics for posterity. He became a trustee for the American Museum of Natural History, and a contributor to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and would finance art shows and exhibitions. George Pratt was an early sponsor of the Boy Scouts of America, and served as President of the American Forestry Association.

At various times he held positions with the American Federation of Arts, the New York Zoological Society and was treasurer of the American Association of Museums, all credentials and qualities to qualify him as a good public servant, admirable above of those selected only by political patronage and loyalty to a demagogue.

In 1915, realizing the abilities George Pratt had developed, Governor Charles Whitman appointed him Conservation Commissioner after reorganizing the Conservation Department, which previously had multiple administrators and then included management of State Parks.

Pratt laid many of the foundations for bird, game and forest preservation in New York State. During his time as Conservation Commissioner (1915-1921) he also increased recreational opportunities on state lands, including building the first lean-tos, instituting trail marking and a mapping system, and building the first public campgrounds. He was also responsible for the controversial tent platform leasing system.

Pratt laid many of the foundations for bird, game and forest preservation in New York State. During his time as Conservation Commissioner (1915-1921) he also increased recreational opportunities on state lands, including building the first lean-tos, instituting trail marking and a mapping system, and building the first public campgrounds. He was also responsible for the controversial tent platform leasing system.

Pratt on occasion used his personal wealth to the benefit of all of New York’s citizens, such as supplying uniforms to conservation officers. Certainly the path for doing good works is eased by the surfeit of wealth.

Realizing the glacial pace at which deliberate governments move, and realizing that some real estate opportunities last as long as fresh strawberries, Pratt, who had plans to make Saratoga Springs the greatest health resort in the world with the erection at the of a pair of bathhouses, a year-round hotel, and tennis and golf courses within easy access of each other, purchased 600 acres there and held it until the legislation could be completed. His idea had always been to build permanently and for the future, and he extended himself financially to that end.

In 1920 Commissioner Pratt brought with him to Saratoga Springs his private landscape architect, James Leal Greenleaf (1857-1933), to design the landscape of the Lincoln and Washington Baths at the State Reservation.

The July 23, 1920 Saratogian reported that Mr. Greenleaf, “Will give especial attention to the Geyser Park and to the Vale of Springs. In the Vale is soon to be erected the bronze statue which Commissioner Pratt will give to the city and work on which is now in progress. It is expected that the statue will be placed by early fall.” Sculptor Alexander Phimister Proctor (1850-1960) was preparing this statue.

The July 23, 1920 Saratogian reported that Mr. Greenleaf, “Will give especial attention to the Geyser Park and to the Vale of Springs. In the Vale is soon to be erected the bronze statue which Commissioner Pratt will give to the city and work on which is now in progress. It is expected that the statue will be placed by early fall.” Sculptor Alexander Phimister Proctor (1850-1960) was preparing this statue.

In his autobiography, Sculptor in Buckskin, which Proctor began writing in the late 1930’s when he was in his seventies, we learn of his 1860 birth and early life in Ontario, Canada and his first meeting George Pratt, who visited his Manhattan studio in 1909.

Both men were members of the Boone & Crockett Club, an early wildlife conservation organization, and enjoyed each other’s company. The two men made a hunting trip together to Alberta in the summer of 1912, and the following year to remote parts of British Columbia to gather specimens for the Smithsonian Institution.

In 1917 Pratt commissioned A. P. Proctor to create the “Mohawk Warrior” sculpture, intended for Saratoga Springs. The artist had created several sculptures of pioneer settlers and Native Americans, and he once told the Christian Science Monitor, that his dream was, “to do a piece of work that will typify all the wild courage, all the colorful romance, and the high spirit of adventure of the pioneer days in America.”

He also was quoted as saying “I have no patience with civilized Indians. I always get my models from among the few real American Indians now living in the west.”

Indeed Proctor would travel to the Blackfeet Reservation near Browning, Montana seeking the right model. The Native American he hired was named Big Beaver, and Proctor described him as about thirty years old. The enlightening differences between these two men made for an interesting trip to the Manhattan studio, as both had much to learn about their companion’s culture.

The New York Times of May 23, 1920 reported that Proctor had completed the large fountain figure for George D. Pratt, who was expected to present it to the State Reservation at Saratoga:

The New York Times of May 23, 1920 reported that Proctor had completed the large fountain figure for George D. Pratt, who was expected to present it to the State Reservation at Saratoga:

“The figure is that of a Mohawk Indian crouching on a rock and letting the water pour over his outstretched hand. The Artist has made the most of his opportunity to emphasize the beauty of muscular energy and coordinated gestures. The pose is natural and beautiful; the slight twist at the waist of the bending body is kept well on the safe side of contortion, yet is sufficiently marked to lend a high degree of vitality to the anatomical composition. Much research has gone to the rendering of this restrained, powerful motion. The limbs, especially the arms, quiver with strenuous life, each muscle is clearly defined under its thin drapery of flesh, not an ounce of surplus tissue interfering with the free and visible play of the bony and muscular framework.”

The admirable result of the “Mohawk Warrior” sculpture is perhaps due to having been contrived by a patron and artist who were peers and comrades, in frequent propinquity, in the vicinity of a campfire.

The previous autumn, Commissioner Pratt spoke to the Saratoga Chamber of Commerce where he said that the state was prepared to spend four or five millions of dollars in the development of the state reservation there if gambling were stamped out, with the “if” being unalterable. He felt Saratoga could be either a world-class Spa or a gamblers’ Mecca, but not both.

The October 24, 1919 Saratogian excerpted the speech:

“I should like to impress upon you as strongly as I can that no one can be more interested in the answer to this great question than the Conservation Commission itself,

than I myself, as commissioner, because, as you of course realize clearly, the State of New York has begun in Saratoga a development of the utmost importance to all of the

people of the state and even to the nation and world at large, and has entrusted that development to my administration. Accordingly, I hope that you will receive all that I

have to say in the same spirit of sympathy and deep interest with which I utter it, because we are all bound up together in the highest development of this wonderful health resort.”

It was not thoroughbred racing that Commissioner Pratt objected to, but the riffraff of followers who were catered to by cheap poolroom owners with backroom roulette layouts, and the itinerant professional dicer looking to clip the gullible, along with some of the other attendant vices. These factors caused George Pratt to revise the “Mohawk Warrior” sculpture’s location.

The sculpture had been conceptualized and planned to be placed near a Saratoga geyser, with his hand extending into that restorative flow in their productive hunting grounds.

The sculpture had been conceptualized and planned to be placed near a Saratoga geyser, with his hand extending into that restorative flow in their productive hunting grounds.

When Commissioner Pratt’s term as the Conservation Commission drew toward a close, he enrolled as a lifetime member in the New York State Historical Association and decided that the Lake George Battlefield Park was a more appropriate location for the “Mohawk Warrior” sculpture.

The dedication of the bronze statue took place on October 4, 1921 in the presence of 200 onlookers. Due to the absence of George D. Pratt, who was on his way to Europe via Alaska, the presentation was made by his brother, Frederick B. Pratt.

The sculpture was accepted by Dixon Ryan Fox, on behalf of the New York State Historical Association, who after expressing gratitude mentioned that the $50,000 sculpture is, “a valued gift; it will be cared for and transmitted untarnished and unharmed to the succeeding generations.”

It is nice to learn this obligation and commitment is being met at the Lake George Battlefield Park.

Illustrations, from above: “Mohawk Warrior” at Lake George Battlefield Park in 2020; portrait of George Dupont Pratt (Amherst College); Governor Whitman and Commissioner presenting medals to Game Protectors, 1918 (NYS Archives); portrait of sculptor A. Phimister Proctor published in The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society, 1919; American Magazine of Art details Proctor completing an “Indian Fountain Figure” for Pratt “to be erected on the Saratoga State Reservation”; and a July 23, 1920 Saratogian article describing the planned placement of the sculpture Saratoga Reservation.

Source link