Education in New York: The Industrial Era

Late nineteenth-century New York experienced rapid growth in both population and industrial activity. Its cities overflowed, as migrants from the farms of the Northeast and immigrants from overseas poured in, seeking opportunity.

Late nineteenth-century New York experienced rapid growth in both population and industrial activity. Its cities overflowed, as migrants from the farms of the Northeast and immigrants from overseas poured in, seeking opportunity.

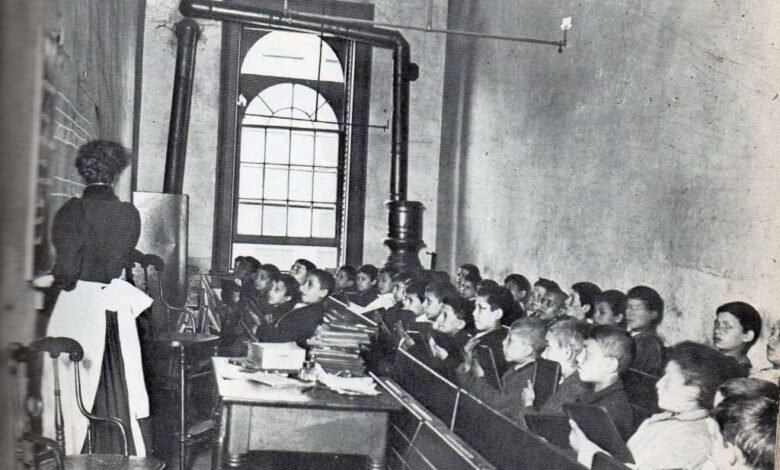

Education reflected this trend, as the growing thousands of children enrolled in schools that were themselves increasingly large and complex in organization and linked with others in vast systems.

Schools also found themselves turned to as agencies that might facilitate the new industrial era and ameliorate some of its rough spots. The public hoped that schools might contribute to the “Americanizing” of immigrants, to the social sorting of youth destined for factory or shop, and to the reduction of social class conflict.

Essential to any broad social role for schools was their universality. In rural areas, this meant the improvement of sometimes rudimentary schools through the raising of standards of teaching and by extending the school year. This cost money, and major steps were taken in the 1850s to expand the State’s financial assistance to the poorer rural school districts.

Along with this money came an effort to eliminate tuition fees which were believed to exclude some pupils. Most cities eliminated tuition in the 1840s and 1850s, and it ended statewide in 1867. As the proportion of urban youth increased, the idea of compulsory school attendance was frequently proposed.

This was a controversial question, since such deprivation of liberty, practiced in some European countries, seemed contrary to our democratic traditions. On the other hand, the State’s responsibility to care for neglected and disorderly youth, who neither attended school nor worked, was generally acknowledged.

The State’s first compulsory attendance law was adopted in 1874, but like similar laws elsewhere, it was susceptible to only incomplete enforcement. In fact, city schools were so overcrowded that they had to turn away many eligible applicants, and would have had no way to accommodate all the truants had they returned.

While the schools of the State theoretically sought to enroll all the children of the State, one group was conspicuously excluded. Before the Civil War, most cities of the State required Black children to attend separate “Colored” schools, sometimes taught by Black teachers.

After the War, a trend toward desegregation reflected the principles of racial equality of the Reconstruction era. In part as a result of the State Civil Rights Act of 1873, and in part because of organized pressure from Black citizens, most cities opened their regular schools to Black children in the 1870s and 1880s.

After the War, a trend toward desegregation reflected the principles of racial equality of the Reconstruction era. In part as a result of the State Civil Rights Act of 1873, and in part because of organized pressure from Black citizens, most cities opened their regular schools to Black children in the 1870s and 1880s.

As urban school systems grew, educational leaders perceived a need for a more elaborate and refined organizational structure. By the late 1800s the typical urban school was graded, with pupils divided into 12 or 14 half-year grade levels, each taught by a separate female teacher.

These teachers were generally governed by a male principal who, in turn, reported to a professional city superintendent of schools. The role of citizens in this arrangement was a subject of controversy.

While some people favored the virtues of citizen participation typical of rural school districts, the trend was towards the insulation of schools from the influence of parents and other average citizens. In New York City, for example, a reorganization of the Board of Education in 1896 eliminated the previously powerful local Ward School Trustees.

In 1917, the Board’s membership was further reduced to just seven, chosen from the citywide elite. Under such a board, it was argued, the professional educators would be more free to shape a modern school system, designed to meet the complex needs of the industrial city.

This part three of four-part series on the history of education in New York State drawn from Consider the Source New York’s Researching the History of Your School an online collection of resources from the New York State Archives and the Archives Partnership Trust. The resources include history, historical resources and how to access them, and activities to use when teaching school history or researching a local school.

Illustrations, from above: Jacob Riis’s photo of boys at a Lower East Side elementary school in the late 19th century; and a circa 1880 view of people standing outside the Black High Street School in Geneva NY, built in 1853.

Source link