When investigative journalist Seymour “Sy” Hersh is asked what made him a suitable candidate to run his father’s store in Chicago, he shrugs, “Pizazz. Like people.”

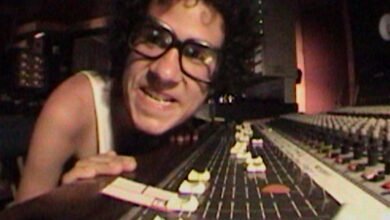

Pizazz and liking people not only equipped Sy to work front of house at Isador Hersh’s dry cleaning business, they have made him appealing to journalistic sources across an extraordinary 50+ year career and they permeate this scintillating documentary by Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus. Hersh’s language crackles with a mordant Yiddish brevity such that even when describing US war crimes and torture, he never loses his powers of speech.

Get more Little White Lies

Aged 88, his brain has lost none of its sharpness as he recalls the damning details of the atrocity that made his name. On 16 March 1968, in the Vietnamese village of My Lai, hundreds of unarmed men, women, children and babies were rounded up and shot dead, but when the Army reported the incident later they said they killed 128 members of the Viet Cong. It took another year for a sceptical young reporter to respond to a tip and begin unravelling the institutional lie, travelling up and down the country to record first-person testimonies from US Army soldiers who executed the massacre.

Hersh tracked down Paul Meadlo, a former farmboy so unhinged by what he had been a part of that he was willing to speak on camera to CBS about shooting at babies, and the gang rapes perpetrated by US soldiers. It was Meadlo’s mother who gave Hersh the infamous line about the Army: “I sent them a good boy and they made him a murderer.”

Poitras and Obenhaus illustrate Hersh’s recollections with media coverage that blew up in the public domain to become part of our collective understanding of US atrocities during Vietnam, but also – grippingly – Hersh has granted them access to his own source materials, while ferociously protecting the sources themselves. We see a vertical print sourced from the army; it’s a black and white map of My Lai annotated with blue felt pen. Over one arrow it says, “30−40 bodies found in ditch,“; over another, “Had lunch“.

“I don’t psychoanalyse those that talk to me, just like I don’t psychoanalyse myself, thank god,” says Hersh early doors, possibly regretting saying yes to this documentary 20 years after Poitras first approached him. Still, because he likes people and has spent his career listening to them (without necessarily believing them), he has a standard of careful insight into why things happen the way that they do. As he reflects on why no one involved in the My Lai massacre reported it earlier, he gives two possible theories: one, that it felt so terrible as to be unspeakable; the other, more likely in his view, “Well, that’s just another day in Vietnam.”

These comments invoke a shiver because you could as easily say, “That’s another day in Abu Ghraib,” or, “That’s another day in Gaza”. The use of war crimes and their attendant cover-ups is presented as a matter of rinse-repeat in US foreign policy as made irrefutable by Hersh’s diligent reporting. For the film is a sprint through the stories he went on to cover, from Watergate to Iraq to Gaza today, amounting to an ironclad reason to mistrust the official US version of events.

Laura Poitras was last in Venice with her Nan Goldin vs the Sacklers documentary, the Golden Lion-winning, All The Beauty and The Bloodshed. If Cover Up feels more conventionally structured than her previous works, it is worth bearing in mind that she is sharing the directing credit with Mark Obenhaus, a documentarian who has worked with Hersh before and earned the (wary) trust of a man who has witnessed the worst abuses of it.

Still, Poitras’s trademark sensitivities and sophistication shine through in the inclusion of her voice during conversations with Hersh. For a professional portrait of a legacy figure who has exposed the coldest deeds, this film has a warm lifeforce, pulsing with the personality of a man whose instincts towards the truth mean that he gives more away about himself than he might have wanted to.

A third of the way through the film, we are taken back to Hersh’s formative years in Chicago and learn in broad, economical strokes the facts of his ancestry. Neither of his parents – Eastern European Jews from Lithuania and Poland – ever spoke about the Holocaust. There is a poetry to the fact that their son has dedicated his life to speaking on state-sanctioned crimes against humanity.

The film gallops every onwards, wheels greased by Hersh’s brilliant and prickly voice. He has a way with words that would make a hard-boiled detective novelist jealous. “There was this story that seemed impossible: it was called the truth,” he says, rifling through one of many manila folders in a home office full of America’s worst kept secrets. Poitras and Obenhaus elegantly juggle focus between the stories themselves and the climate the storyteller was working in.

They source juicy clips to illustrate the hostile reactions to all of Hersh’s endeavours, from Nixon calling him a “son of a bitch” on the leaked tapes, to up-in-arms regular Americans calling talk shows to call him unpatriotic. Then there is the insidious behaviour of The New York Times. Hired in 1972 in the glow of winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1970, he quit in 1979 shortly after he discovered that the corruption he was reporting on at the conglomerate Gulf & Western Industries was uncomfortably close to home for his colleagues. Now he reports using Substack.

Poitras questions him on the less glorious moments of his career, too, so that he emerges as a flawed human rather than a bastion of perfect judgement. This is not a perfect documentary either, with the breathless dash through his post My Lai journalism sometimes feeling overwhelming. Yet perfection is not the point when something impossible has been bottled: it’s something called the truth.