Circus Broadsides: Preservation of New York History

The New York State Museum’s circus posters, shared as part of their “Look at This” social media series, inspired the State Library to digitize circus-related documents found in their collections.

The New York State Museum’s circus posters, shared as part of their “Look at This” social media series, inspired the State Library to digitize circus-related documents found in their collections.

Their search for NYS Library circus materials began in the Manuscripts and Special Collections Unit, where they found circus broadsides from NYS and beyond. Most of these date back to the mid-nineteenth century and are over 150 years old, making their condition and the vibrancy of the ink all the more striking.

An undated broadside advertising Van Amburgh & Co.’s Great Golden Menagerie (Van Amburgh Circus operated from 1821 to 1889) tells of the addition of a black rhinoceros to their exhibition.

An undated broadside advertising Van Amburgh & Co.’s Great Golden Menagerie (Van Amburgh Circus operated from 1821 to 1889) tells of the addition of a black rhinoceros to their exhibition.

Text from the broadside reads, “It had long been the desire of Van Amburgh & Co. to add to their Menagerie, already acknowledged to be the most complete and extensive in America, a living Rhinoceros, and for many years they have been steadfastly endeavoring to obtain one. But the difficulty and extreme hazard of its capture, together with the almost insurmountable difficulties of transportation, have prevented the realization of their desires until recently.”

The broadside explains that when the rhinoceros arrived in New York from Africa, “descriptive and congratulatory articles were published in almost every one [of the New York papers] in the city.” Despite a tear at the top of the document, we can make out this impressive claim: “This is emphatically the most colossal exhibi[tion of] the nineteenth century.”

Dramatic rhetoric is found throughout the circus broadsides. A New York Circus advertisement for “Grand Equestrian Feats” at Vauxhall Garden assures the public that, “no expense or exertion shall be spared to render the Circus a place of Amusement worthy a continuance of fashionable and public favour.”

Dramatic rhetoric is found throughout the circus broadsides. A New York Circus advertisement for “Grand Equestrian Feats” at Vauxhall Garden assures the public that, “no expense or exertion shall be spared to render the Circus a place of Amusement worthy a continuance of fashionable and public favour.”

Acts on horseback included Roman gladiators, Gulliver and the Lilliputians (the roles of the Lilliputians filled by the director’s grandchildren), and a masquerade ball.

Highlighting another NY circus, a cropped section from an advertisement for LaFayette’s Circus (above), named for General LaFayette, announces the attendance of the General at their performance that evening.

“In honour of our Illustrious Visitor, the Proprietors have determined to exhibit this evening the greatest display of Horsemanship ever witnessed in the United States.”

The NYS Library’s vast collections are not limited to items from or about NYS.

An 1866 advertisement for Barry’s Grand National Circus at Linen Hall in Chester, England features circus acts like the “great troupe of vaulters,” “canine wonders,” and “the highest leaping pony in the world.” Worthy of note is the preservation of the bright red ink on this document.

An 1866 advertisement for Barry’s Grand National Circus at Linen Hall in Chester, England features circus acts like the “great troupe of vaulters,” “canine wonders,” and “the highest leaping pony in the world.” Worthy of note is the preservation of the bright red ink on this document.

The Performer’s Perspective

Books from the State Library’s collection provide insight into the experience of circus workers from the time of these broadsides.

The Autobiography of a Clown, a book published in 1910, tells the story of European Jules Turnour as told to Isaac F. Marcosson:

“It did not take me long to find out that to be a successful clown in America you had to make local hits, just the way comedians did on the stage. The tents were not nearly so large as they are now and you could talk to your audience and be readily understood. Accordingly, I made haste, as soon as I reached a town, to get a local newspaper, find out what was going on, and then I made reference to it in my clowning. It never failed to please the spectators.”

A different type of experience of a circus traveler in the U.S. is recounted in My Circus Life by James Lloyd in 1925.

Lloyd believes he came close to losing all his money: “on arriving in New York, two days before sailing for England, my friend took me to see the sights in the Bowery. That part is worse than Whitechapel.”

Lloyd believes he came close to losing all his money: “on arriving in New York, two days before sailing for England, my friend took me to see the sights in the Bowery. That part is worse than Whitechapel.”

He lied, claiming not to have small bills, to avoid having to take money out of his pocket – he had all the money he had saved that season, 300 pounds, in a roll, and believed he would have been robbed had he exposed how much money he had.

Both Turnour and Lloyd paid attention to tragedies, personal and otherwise, that they dealt with in the course of their work. They both traveled from Europe to perform in the U.S., far from their families for long periods of time.

Often, they had to perform shortly after receiving terrible news. Accidents and injuries were common, and, of course, the show was expected to continue immediately.

Boisterousness in the circus environment was also expected: the broadside for LaFayette’s Circus promises the presence of active officers on site, and that “the public may be assured that any riot or disturbance will be most promptly suppressed.”

Narratives from circus performers like Turnour and Lloyd gave shape to a deeper, human element that existed amidst the rowdy and sensationalized circus entertainment advertised on broadsides.

Preservation at the New York State Library

The Preservation Unit at the NYS Library engages in important work to ensure the longevity of documents important to the history of NYS.

A variety of factors are considered when determining how to appropriately care for a document, such as the type of paper the document is written or printed on, the type of ink that was used, or the size of the material.

Fragile documents can be encapsulated in mylar, tears can be repaired, and an item’s housing can be changed to better protect the material. The use of acid-free and lignin-free folders to avoid degradation of documents is essential.

The Library protects paper from light, both natural and artificial, by keeping books closed and properly housing broadsides, maps, and other flat documents. These methods also protect against the fading of iron gall ink.

Fasteners, like paper clips, staples, or rubber bands, can damage materials and are removed. Sometimes, an item is folded (a map folded as an insert in a book, for example) and a decision is made to flatten it – a careful process that takes place in the Conservation Lab and involves a humidification chamber, non-woven spun polyester fabric, and blotting paper.

Prior to digitizing manuscript material, the Library’s digital scanning team meets with the Preservation Unit for an assessment. Information is communicated about how to handle documents and attention is brought to specific concerns.

Sometimes, the binding of a book cannot be opened past a certain point. Other times, documents are so fragile they cannot be removed from mylar for digitization, and the digitization team takes steps to capture a quality digital object while avoiding glare.

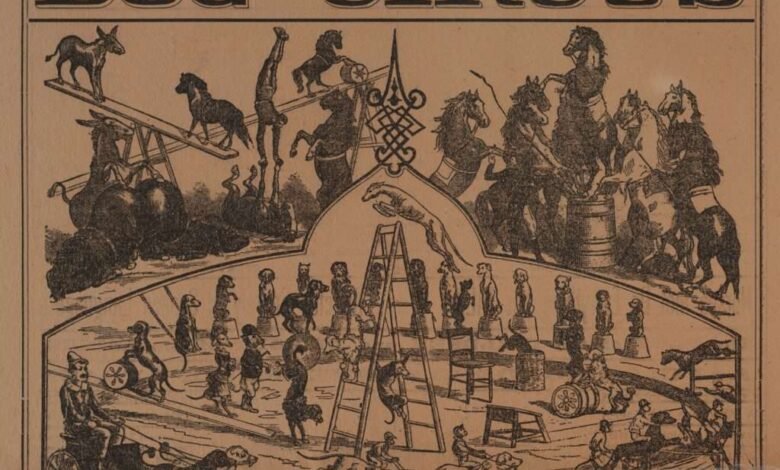

Some of the Library’s circus broadsides were torn and have been repaired by gluing Japanese tissue on to the poster using cooked wheat starch as the adhesive using fine paint brushes and tweezers.

Japanese tissue is a fine, strong, pH neutral paper made from either mulberry or gampi shrubs. It is available in a variety of weights, thicknesses, and colors and is used in many different book and paper repairs, including mending torn pages. Cooked wheat starch paste is a pH neutral adhesive that dries clear and remains flexible after it dries.

An example of a repaired tear can be seen near the bottom of the undated advertisement for Sparks Bros. Circus, boasting “Comical and Mirth-inspiring Dog Circus: Canine Instinct Cultivated to its Fullest Extent.”

An example of a repaired tear can be seen near the bottom of the undated advertisement for Sparks Bros. Circus, boasting “Comical and Mirth-inspiring Dog Circus: Canine Instinct Cultivated to its Fullest Extent.”

Other circus-related items have been encapsulated in mylar. If necessary for preservation, maps, posters, and other large single or double-sided items are encapsulated or sandwiched between sheets of archival polyester to protect the maps etc. from damage when it is handled.

During encapsulation, an ultrasonic welder is used to seal the polyester sheets together. Unlike a laminated document, encapsulated items can be safely removed from the polyester sheets if needed.

Preservation considerations expand beyond the documents themselves to include monitoring collection spaces for insects, mice, and other creatures as well as for leaks and other building-related issues.

Preservation staff also monitor temperature and relative humidity in collection spaces, clean books and exhibit spaces, consults with NYSL staff on projects (loans, exhibits, scanning), organizes NYS Library emergency preparedness in collection areas, and coordinates commercial binding and microfilm duplication.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of preservation. Preservation measures taken in the NYS Library’s past ensured that we were able to open these folders of circus broadsides and still see such vibrant ink.

The Library is able to handle and digitize fragile documents with confidence because they were either repaired or encapsulated. The NYS Library’s work to preserve the documents in their custody over the last two centuries continues to preserve access to the history of NYS and beyond.

Read more about circuses in New York State.

A version of this essay was first published on the New York State Library Blog. The New York State Library, established by law in 1818, collects, preserves and makes available materials that support State government work. The Library’s collections, now numbering over 20 million items, may also be used by other researchers on-site, online and via interlibrary loan.

Illustrations, from above, courtesy the New York State Library: LaFayette’s Circus LaFayette’s Circus advertisement between 1824 and 1825; Van Amburgh’s Great Golden Menagerie, n.d.; New York Circus broadside advertising a theatrical and equestrian performance at Vauxhall Garden in the Bowery, New York City; 1866 advertisement for Barry’s Grand National Circus at Linen Hall in Chester, England; photo of a clown (probably Jules Turnour) from the frontispiece of Autobiography of a Clown, 1910; and an advertisement for Spark’s Bros Dog Circus, n.d..

Source link