Carol Kammen: Like It Or Not, History Isn’t Rosy

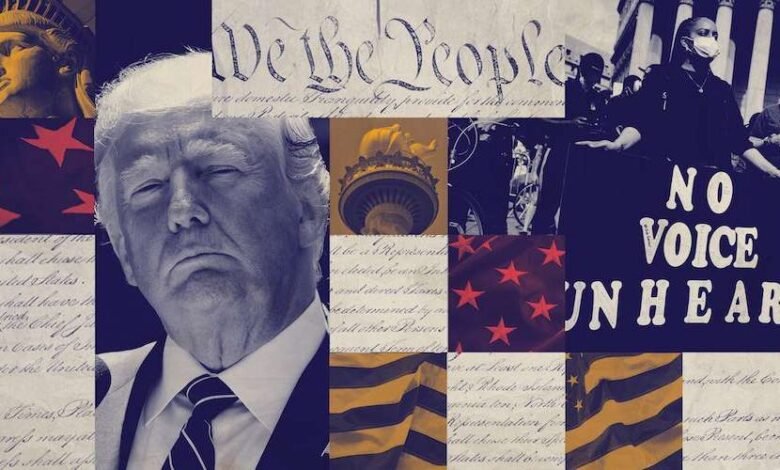

The White House has issued complaints about the history on display in our national museums, complaining that it is too negative, that it portrays the past as a place of hurt.

The White House has issued complaints about the history on display in our national museums, complaining that it is too negative, that it portrays the past as a place of hurt.

Yet, I would argue that historians, those in the academic world, museum directors, and local historians have been doing their job — and doing it well.

I am a local historian, writing mostly about the place where I live and the region that surrounds it.

By listening and observing the work of others, I have learned about Rosie, a young immigrant woman who led a strike in 1913 in Auburn, New York.

I have come to see H. H. Coleman as an inadvertent historian whose columns in the Colored American in the 1880s, described the social life of Black people in my town.

I have learned about Juanita Breckenridge Bates who led the fight for suffrage in my town and the curious fact, that her husband, in 1917, forgot to turn over his ballot to affirm the fact that women should have the vote.

I have learned about Lizzy the enslaved woman who was suddenly “disappeared” from her home in Caroline and sold in the south just as New York was passing a law in 1827 to abolish slavery in the state.

I have come to know about Rev. Henry Johnson who brought the AME Zion church in Ithaca into being, but while lecturing around the state was beaten 17 times.

I know that the first Jewish rabbi in Ithaca arrived in 1915 where he and his wife had a child; then moving on to Alabama his family was listed as having a child born in Ithaca — with Greece written in pencil above young David’s name, no one in Alabama knowing about Ithaca, New York.

Small things. But they tell a greater picture. That life in the past was not always a rosy place, that laborers had to strike for better working conditions, that Black people fled here and then away again because this was not far enough away from the federal marshals unleashed by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

I learned that local women worked hard to achieve equality in the law by sending a petition to Albany in 1878 asking that the word male be removed from the state constitution, and that petition, while registered, was then deposited in the trash and never heard of again. So, the women had to go to work again to gain equal rights.

Opening up the faults of the past does not tear down our country but it aids us in raising above it. It allows us to see that we can change for the better, recognize our faults and strive to bring about a pluribus unum.

The truth of the past allows us to see that problems and faults can be overcome, that there are moral truths worth fighting for, that individuals matter.

It is this diversity that has been uncovered over the past 50 years that has broadened our view of the past and is displayed in museums across the land.

This country was not a place of peace and harmony but a place where individuals had to step out of line to make “good trouble” to bring about necessary change.

That story needs to be told ‘lest we believe that the past was unlike the present where there are tensions and contests and inequities that need to be resolved for this be a true democracy.

Historians are doing their job. It is now up to those in power and voters to see that where there is inequity we work for fairness, where there is harm, we bring balm, where there is strife we talk to each other to make the country and the world better places.

New York Almanack is reporting on the Trump regime’s impacts in New York State, but we can’t do it without your help. Please support this work.

Illustration courtesy the American Civil Liberties Union.

Source link