Bob Mould on Husker Du, Aging Indie, Trump, and Pro Wrestling

B

y his own admission, Bob Mould is not a Zoom kind of guy, at least not in terms of the video aspect. During the early months of the Covid lockdown, he passed on doing any of those briefly in-vogue virtual concerts. “People were saying, ‘Oh, come on, you could do Zoom concerts,’” he says. “And I’m like, ‘No, you don’t understand. That’s not what performing music is. Performing music is when people get together in a room and create a community.’ The idea of doing Zoom from my work room was frightening. No interest whatsoever.”

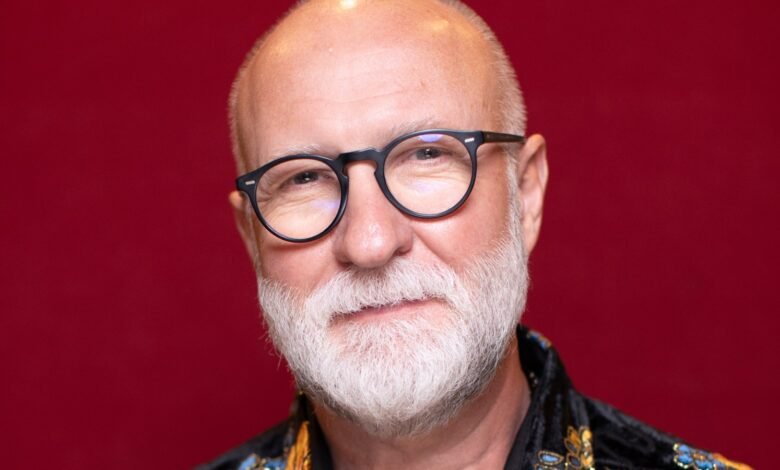

And last week, when he called into Rolling Stone, Mould still wasn’t much of a Zoom guy. After expecting to have an audio exchange, he good-naturedly agrees to flip on his camera. “No worries,” he says. “You’re more modern than I am.”

The Mould who pops up on screen is bespectacled and white-bearded, which befits his role as one of the elder statespeople of indie rock. Forty-six years after the launch of Hüsker Dü, the Minneapolis hardcore trio that would venture far beyond that subgenre, Mould has, as he says, “been through a lot.” Over the course of those decades, he’s dealt with the rise and flame-out of that band and saw indie became big-time alternative rock in the Nineties. Along the way, Mould stopped his own hardcore drinking, came out as a gay man, announced a farewell-to-rock tour that didn’t last, immersed himself in electronic music and DJing, wrote scripts for World Championship Wrestling, penned a memoir, and lived everywhere from New York City to Berlin.

Mould has also been one of indie’s most productive music makers. His just-released Here We Go Crazy is his 15th solo album, not counting his records with Hüsker Dü and his subsequent band Sugar. Working once more with bassist Jason Narducy and drummer Jon Wurster, his regular rhythm section since the early 2010s, Mould has blasted out another collection of alternatively tormented and guardedly optimistic rants and raves.

Now based in San Francisco, with occasional retreats to the Southern California desert, Mould admits to feeling somewhat more settled these days. “I’m pretty content with life,” says Mould, who married his partner, Don Fisher, in 2023. But he’s also had to cope with the recent deaths of colleagues like producer Steve Albini, the Replacements’ Slim Dunlap, and especially his Hüsker Dü bandmate Grant Hart, who died of liver cancer in 2017. Last year, Democratic vice presidential candidate Tim Walz confirmed his Hüsker Dü fandom, a brief see-a-little-light moment before Kamala Harris and Walz’s loss. And Mould is now dealing with a rattling post-election world that could easily target same-sex marriages like his.

“It’s been sort of crazy lately,” he says. “But, you know, just trying to stay busy.” As always.

Hüsker Dü, 1980

Steven P. Hengstler

When we spoke a few months ago, you were thrust somewhat into the national conversation when Beto O’Rourke tweed that he and the Democrats’ VP candidate, Tim Walz, bonded over Hüsker Dü.

Tim Walz, yeah. [Sighs] What a wild day that was, to hear about the Beto O’Rourke tweet and the ensuing madness. Tim Walz seems like a super-decent guy. Minnesota has been such a leader in progressive ideas. Seemed like a good fit. Too bad things didn’t go better in the election for all of us.

Did you get any MAGA blowback?

No, I think I’m off their radar. Their radar seems to be malfunctioning at the moment anyway, so let’s just hope we can keep the airplanes in the sky, right?

What are your feelings right now about the state of the country?

It’s the end of an era, this great experiment we put together. I don’t know how we get out of this. I’m 64. I’ve seen a lot. Nothing like this. I don’t even know where to start. Every single person, whether you stand up against the MAGA movement or whether you’re part of it, you’re going to feel it, unless you’re in the very tippity, tippity top of the one percent or maybe the top two percent of income earners in America. Somebody’s going to lose their job. Somebody’s going to lose their house. People are going to lose their lives. Some people are going to lose their rights. I don’t see anybody gaining anything except the very tippity top of this scheme.

I don’t want to hear about buyer’s remorse. I don’t want to hear, “Oh, you’re just exaggerating.” I don’t want to hear any of that anymore. This is beyond a five-alarm fire.

As a gay man, how are you feeling, especially when same-sex marriages may be targeted as well?We knew this was coming. I’m very grateful that I live in California, where the elected leaders protect all citizens of our great state. I’m going to be probably okay to really bummed out; that’s sort of my range. A fair amount of my annual income goes to the best possible healthcare I can buy.

I don’t think my life is in danger, but I feel like my rights are. My husband and I sit at the dining room table with all of the paraphernalia that ends up in our mailbox in San Francisco, talking about “yes” on this proposition, “no” on that proposition. We sit there with this 150-page book [each election], and we read through all of it, and that’s how we vote, because that’s our civic duty. For people who only get interested in politics every four years, we’ll see what you get.

It’s all about whether people have the resources to fight an improper IRS audit, once all that data gets amalgamated. I feel for the people who don’t have the means to defend themselves, because when they lose the legal system, or they lose justice as recourse, a lot of people in America are going to be defenseless.

Gender certainly played a role in the election.

I feel most terrible for trans youth in areas outside of California or New York or Illinois or Massachusetts, places where people are progressive and thoughtful and compassionate. It really hit me last September and October, when I did a solo electric tour. I played Orlando on a Saturday, then had a 650-mile drive to North Carolina. In the rental car, I had TuneIn. They can geo-locate my movements, so the ads were targeted for my location. I’m going through South Carolina, and all of a sudden I get my first exposure to the Trump trans ad campaign, which basically said, “Kamala is for they/them, Donald Trump is for you or us.” When I heard that, my heart sank, because at that moment, I feared it was going to work.

What was the rest of that tour like given the election was coming up?

I first played the Northeast and Midwest, so, friendly territory. I started building a monologue I would use in the middle of the show to explain my political stance, telling my story growing up in a small town in the Adirondacks, knowing I was a homosexual and that I had to move to a big city to feel safe, and then a decade of closeted life, especially in the Eighties. I would get up and tell people these things, and I would talk about getting married and how important all of that is to who I am and what I do. I just laid out my case in five to seven minutes. And each night I would end my monologue with, “And this one’s for all of you who say, ‘Shut up and play.’” And then I would play “Too Far Down” from Candy Apple Grey. I hope that monologue and that song and the contents of it would hopefully make a difference to people if there was a question about sexuality or any of that stuff.

So September leads to October, and I go into the deep South: Baton Rouge, home of the Federalists, and Jackson, Mississippi, and Memphis. I’m going into places that are less than friendly. I don’t have to, but I choose to include this monologue in these shows. In Atlanta, people were hooting and hollering, like “Fuck, yeah! Fuck them!” Jackson and Baton Rouge, not so much. [Laughs] I’m not knocking anybody or knocking a town, but that’s just the observation from the stage as I’m watching my congregation. It ranges from confusion to “do we really have to do this during a rock show?” to “fuck those guys.” In a couple places, it tipped more to the conservative side. And I’m a guest, right? I don’t want to start haranguing people. But I needed to show them who I am and what I do and why we’re here. Hopefully, a few people got it.

How does art and music respond in a time like this?

I preemptively protested with the Blue Hearts album back in September of 2020. That record was very political. It’s funny, because it sort of picked up where I left politics in the fall of 1983 [laughs], three years into the first Reagan term. Right before Zen Arcade, Hüsker Dü collectively made a decision to step away from punk politics and get more punk personal. So Blue Hearts, three years into Trump, was me revisiting that idea. So that was protest. The inner sleeve was my homage to Phil Ochs with the gun.

But what is the purpose of art? I can only speak for myself. I’m getting old, but I walked seven and a half miles yesterday. So if there’s a protest, I should be able to make it. [Laughs]

Hüsker Dü hit its stride during the Reagan presidency. People were using words like “fascist” then, but does that era compare to the current one?

As a young kid, it was pretty shocking to me, going to a super-liberal private arts college, Macalester College, and being astonished at the sight of all these kids with suits and briefcases talking about Ronald Reagan. It was horrifying then. So it’s not without precedent. When Reagan was governor of California, right before he became president, the Moral Majority, the Anita Bryants, the Pat Robertsons and all those people, were already currying favor with the Republican Party. And Reagan made room for them at the table. And that is not unlike what’s happening now.

Bob Mould and his husband

Alicia J. Rose

The biggest difference, two generations later is, is communication. In the Eighties, communication was one way. You wrote an article and it was broadcast and people read it. Radio was for the most part one-way. In the early Nineties, the advent of the internet and digital compression evolved into AOL blogs and message boards and then social media, to where we are now — the algorithm as propaganda. Black-box weaponry. That’s the biggest reason we don’t recognize the world even compared to the Reagan years. They got us. We all clicked the EULA box, and they took it all, and they have it all. And now there’s a dude trying to merge what he’s got with what the other guy that’s in the UFC has got with what the IRS has got. Things that have been intentionally kept separate for centuries in our system are all now being hoarded and amalgamated by people who weren’t elected.

Which part of this are people not understanding? It takes no time to destroy everything. It takes forever to build what we have, and we’re watching a handful of dudes destroy it for no good reason.

Now you have an album called Here We Go Crazy. It isn’t as overly political as Blue Hearts, but did the consciousness of that record spill over into these songs?

After Blue Hearts, I said my piece, and I still stand by those words; they’re appropriate today. For Here We Go Crazy, I was just trying to stay alive, trying to get back to work, spending time with my now husband. “Here We Go Crazy” was the song that brought everything together. What I’m trying to in that song is paint a picture of my new part-time life in the desert, surrounded by the mountains. It’s a very LGBTQ-friendly environment. It feels safe for now. There’s a good community there. I have a lot of quiet so I can do my work. In that song, I’m trying to convey the vastness of it, the sparseness of it. And not unlike Workbook [recorded on a farm in Minnesota], if it gets really quiet, I get a little crazy in the head.

As you sing in “Sharp Little Pieces,” “The misery makes me feel alive.”

Yeah, of course. [Laughs] Fortunately, I have a husband who understands this. He’s a doctor — well, a retired dentist — who’s smart enough say, “You’re just in there doing your work, aren’t you?”

What fueled “Neanderthal”?

With that drum intro, I just started thinking, “This is so dumb. This is so primal.” I use “Neanderthal” as shorthand for knucklehead. The knucklehead is me as a kid, not being particularly sensitive and being, “Fight, fight, fight.” Growing up in a violent house, I was always sort of ready for something, ready for violence, ready for everything I knew to get turned upside down in an instant. The second part of the song is me making fun of myself, like, “Yeah, I’m wild, crazy rocker. Oops. I’m in my 60s!” [Laughs] I’m just poking fun at my early self and my current self.

I thought it might have been a shot at Trumpers.

If the fascist tattoo fits, wear it, right?… The first four or five songs, there’s a lot of uncertainty. Then the sixth, seventh, and eighth songs, we’re going dark, like “How did I end up in this situation?” The top of side two is “Lost or Stolen,” a really dark song. That’s in that [sequencing] spot — look at my blueprint, like “Thumbtack” [at the start of the second half of 1996’s Bob Mould]. “Lost or Stolen” is heavy, a lot of old-school addiction, a lot of modern addiction.

Addiction is weird these days. When I was growing up, my father was an alcoholic. I was an alcoholic. I am an alcoholic. I’ve come close to addiction with drugs, but have managed to stay back from it, knowing that I’m an alcoholic. I started drinking every day when I was 13. I stopped that when I was 25, but that was a quite spectacular run of about 5,000 straight days of being drunk. [Laughs]

But in the new world, you and I could be sitting having a conversation at a coffee shop, and I could be getting ready to end my life because I just lost everything on a gaming site, and you wouldn’t even know. Whereas if you were sitting across from me and I had a dope problem or a drinking problem, you’d see it. The black piece of glass [holds up his cell phone] is the worst addiction. It’s a dopamine machine for all of us.

Thinking of an album like an LP, with sides one and two, is very old school. You still conceive album sequences that way?

Absolutely. To me, the construction of a record is when the tent pole appears. I have to make a tent and have these four corners, the beginning of side one and beginning of side two. And then you sort of secure everything, and then you put all the other pieces inside of it, and then you end up with 30-odd minutes. It’s a blueprint. I didn’t invent it. But I still use it. I’m a creature of the way I’ve always done it.

On your past albums, you’ve mixed it up, venturing into electronic music or more expansive arrangements on Workbook, but you always return to the guitar-bass-drums trio format. Do you ever think, “I’m going to make a country album this time?”

I have those thoughts of going in different directions. That’s what I’m supposed to be doing in my 60s, reinventing and coming up with some huge operatic concept piece or something. But this record is sort of give the people what they want. [Laughs] After everything we’ve been through recently, it’s like, “Here’s a nice, warm blanket. You know these songs already.”

Hüsker Dü was the beginning of me playing in three pieces, then with Tony Maimone and Anton Fier, then Sugar, now me, Jon and Jason. From my perspective as a player, the less people involved, the easier it becomes to improvise. And when I say improvise, I don’t mean free jazz. When you’re onstage and we’re supposed to turn left slowly together on something, it’s easier to feel that turn and be able to turn with it. Or if we want to change a set list on the fly. We have these little baseball signs, like pitch or catch, that we do when we have to make a change. So there’s a functional purpose to three-piece as well. And it’s also about playing lead and rhythm together, that Townshend kind of playing. That’s my thing, and it just feels right for me.

Bob Mould with Sugar in 1993

Gie Knaeps/Getty Images

At this point in your life, what does it take to physically rev up to that intensity?

Okay, so the dirty little secret in the business is: If you love a band and the singer or the drummer are over 60, take a look at their tour itinerary and see how many back to backs [shows] they’re doing. That tells you. I know I’m not as spry as I was in my 20s, and I know that I don’t have the raw power I did in my 30s, but I can still summon that every night, the closest I can get to it. I do not sit onstage. I run around and I am soaking wet after 10 minutes.

The hard part is the recovery. The voice is the hardest thing. It’s a lot of water, a lot of sleep, trying not to scream bloody murder every single night. Just little shortcuts. When I’m on tour, I do not talk. I go to soundcheck, and I do a half a song, and I shut up, and I do 90 minutes, and then I shut up. I might say “Starbucks” or “bathroom.” At the after-show, I’m not going to talk to everybody for an hour and a half. If I do that, the tour is over. I’m going to get a lanyard that says, “Can’t talk.”

Are there certain songs you don’t do anymore as a result?

“JC Auto” off Beaster? [Laughs] I don’t know if I have to do the blood-curdling scream from the last chorus of “Poison Years” every night. If I do that, I’m fucked for the rest of the tour. I hope people understand I’m trying. I’m doing the best I can with it. This is war. I’ve got to be ready. I don’t eat any rich food ever on tour. Because you get older, you get reflux. It’s really a full-time job to try to stay in shape for work.

This may sound like a crazy notion, but the way you and some of your peers still adhere to the sound of Eighties or Nineties indie feels like the way old blues men would stick with their basics.

That’s spot on. I never thought of it that way. Old habits are tough to shake. And a three-piece felt natural: that kind of aggression and melody, and hopefully having a simple but smart approach to the words. You can’t go wrong with that, especially in pop music. I never thought of it in terms of the blues guys, but they had this primitive guitar, unconventional tunings and techniques you would not learn from a guitar teacher. They invented this language. And they keep it and are keeping that language alive as long as possible.

Your genre’s collective language was different from blues-based classic rock, for sure.

Yeah, it was. It was against all of that. It was against the excess, against the exclusivity, against private jets and cocaine and groupies. All of those things seemed unattainable. But when I heard the first Ramones album, it’s like, “I think I can do that.” And so many of us found our way in through that.

You’re part of a generation that invented indie rock in the Eighties, but at this point, it sometimes feels like you’re one of the few people left standing from that genre, along with some of the former members of Sonic Youth. Kim Gordon just got a Grammy nomination.

There’s a fair amount of people left. The hardest working of all of us is Mike Watt. His sheer passion for communicating on a daily basis with music in a new city is mind-blowing. [Henry] Rollins, in a different format, still has a lot to say and a lot to share. Jello Biafra is still out DJing and guest performing. He still puts out Guantanamo School of Medicine records. He’s got Alternative Tentacles the label. And Thurston [Moore] and Kim, and Steve Shelley’s new band, Winged Wheel. There’s still a lot of folks doing it.

We lost Steve Albini last year.

Yeah. The last time I saw him was during basic tracking at Electrical Audio in January 2024. We’d been working on and off at Steve’s place for a decade at least. My last hang with Steve was just getting caught up on how he was doing, whether Big Black was going over to Spain. The next day, he brought me a bag of empanadas from his favorite new restaurant down the street from the studio. Big, big, big, big loss. Steve not only built this incredible cathedral for us to work in, but he also had all the expertise he shared with thousands of bands, his outspokenness and his ability to show new musicians how to stay true to your work. I knew no one like him before I met him. We disagreed on a lot of stuff too, which always made it fun.

Looking back, what is the legacy of that original indie scene?

We built an entirely separate world, a world that that did not exist before we all showed up. Nobody had a plan. Not to drag it back to politics, but I know anarchy, right? I know what it is to burn everything down, go all scorched earth, and then whatever grows is what it is. I get it. In the Eighties, we saw no way into pop music. It seemed like there were barriers to entry to AOR radio. So bands started learning how to put on their own shows at VFW halls and about the power of independent press through fanzines, and how to broadcast a message at college radio. All these things began to coalesce through the mid Eighties, and it created a world that was separate from everything that came before it, and it was all built on community and change and generosity. How many bands slept in the basement of whatever apartment I might have had a room in when they came through Minneapolis? In return for sheltering and feeding a band when you got to their town, they usually would reciprocate.

And that’s before the internet, before cell phones, before GPS, before any of that. You roll into a town and, “Oh, I see a skater kid. Let’s follow the skater. Oh, there’s the skate shop. It’s next to the vegan restaurant. Oh, and there’s the indie record store! Now we can maybe put 20 singles on consignment and get gas money to get to the next town.” That literally was the way we did this thing. And none of it existed before we showed up, and none of us knew we were building it. But then one day it was sort of built, and we’re like, “Oh, right, so we’re paving the roads. Now we’re making the roads really smooth.” And then you get to, like, August of 1991 and “Teen Spirit.” We won. [Laughs] For a while.

You all did, but some of us also thought your band and your peers would also be the next generation of classic rock, so to speak, and it didn’t quite turn out that way.

I don’t know. I don’t know if we were meant to be the next generation of a previous generation. I think we’re okay to be our generation for as long as we’re here. I didn’t expect to inherit anything. It was just like, “I’m doing this thing, and we got to keep doing it, and we’re the best band in the world, and we have to prove it.” That’s what Hüsker Dü was about to me. It wasn’t about “we inherit Quadrophenia” or something.

Bob Mould DJing at the 9:30 Club in Washington, D.C., in 2011.

Mark Gail/The Washington Post/Getty Images

Did the industry expect that, though? You were all signed to major labels.

The Eighties was a weird time. Hüsker Dü, we were fucking oblivious to it. You look at us anytime on MTV and think, “Who are those guys? They are so weird looking.” But R.E.M. especially elevated the whole idea of community, great songwriting, constant touring and doing the right thing as people. They really lifted the whole thing up, even higher than any of the punk bands did, as far as their impact on the society. They were an important band to all of us. We had R.E.M. so I never really found a reason to like the Smiths. I had a lot of respect for them, but I never was a Smiths person.

About a decade ago, the Replacements returned, with Paul Westerberg and Tommy Stinson and two newer members, and they were incredibly well received.

That was completely nuts. I mean, it was great. Me, Jon and Jason played the same Riot Fest that was also the first Replacements show.

Grant Hart was, of course, still with us then. In light of the Replacements’ reception, did it cross any of your minds to reconvene Hüsker Dü and get some overdue props as well?

No. The band blew apart, pretty seriously. When it exploded, it exploded. Grant and I stayed in touch over the years. We played a couple songs together, acoustic, at a show to help raise money for late Karl Mueller, from Soul Asylum. We talked about it the night before, and we didn’t tell anybody, and then we did it, and that was it. Neither of us ever talked about putting Hüsker Dü back together. I was content with my own work. Pretty sure Grant was content with his own work post-Hüsker. A friend of mine was asking about [a reunion], and I just said that sometimes things are meant for a time and a place.

I got no problem with nostalgia or reunions or any of that. I think whatever anybody wants to do is awesome as long as they’re having a good time. But Hüsker Dü was then, and it meant so much to the three of us in the band that we meant so much to people. I didn’t want to take a chance on being less than what people remembered.

We just published a piece about the new generation of hardcore bands like Turnstile. Do you keep up with those?

Turnstile, Narrow Head, a lot of that, yeah. In the current moment, there’s this new heavy sound that feels like it was built on early-Nineties shoegaze, with fair amount of emo from the mid to late Nineties and a little bit of old-school punk rock in it. For me, the last five or ten years, my favorite band is a group from Detroit called the Armed. It’s an art-noise collective, multiple members, six, seven people. They do a lot of amazing videos and the sound is really over the top. They’ve started to go into almost an Eighties goth lane as well. They are putting out some of the best Western pop music.

What about guilty music pleasures?

I’m an unabashed pop fan, so Dua Lipa. I mean, everybody loves her work. I just love her voice. I love the retro house/disco vibe of Future Nostalgia, such a cool record. I’m trying to get into Chappell Roan. Her message is strong and great. Cher on SNL 50, I was like, “Good God, I love Cher so much.” I loved her as a child and watched the TV show. I had all the singles. So to see her still standing and killing it every time was just great.

For a period starting in the late Nineties, you were immersed in the world of pro wrestling and were a consultant for WCW. That’s the world partly responsible for giving us Trump.

[Sighs] I tried to warn people. I tried to explain to them: “Look, this guy is a friend of that guy [Vince McMahon] who popularized this entertainment form.” I had a couple dinners with big DNC people, and I would just say, “You know what this guy is doing, right?” They would say, “Oh, no, too low-brow.”

This would have been 2018, when they were trying to figure out how to stop [Trump]. They would say, “We have to find somebody who can beat him.” And I just looked up and said, “How about Dwayne Johnson?” And they’re like, “Who?” I said, “The Rock, the pro wrestler who understands this kind of entertainment.” There was crickets. I said, “I’m just trying to tell you how this sausage is made, because I got to make it for a while.”

What did you take from that whole experience in pro wrestling?

Pro wrestling at that period was Stone Cold [Steve Austin] and the Rock and [Hulk] Hogan and all those guys. You learn that the more explosions you give people, the more excited they get. The more pyro, the more coarse language, the more T&A that you give people, the more you can engage that cherished demo of 18 to 35-year-old males. And that’s what these guys are doing now, with chainsaws, sexual abuse, fireworks. It’s the same blueprint. And now Linda McMahon is running the education department.

Source link