A World of Pigeons: A Champlain Valley Pigeon Roost, ca. 1785

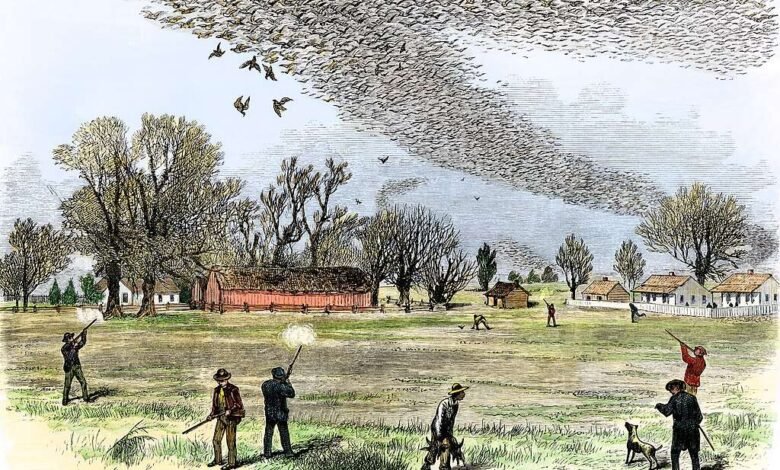

The wild passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was once the most abundant bird in North America, numbering perhaps as many as 5 billion individuals. It migrated in enormous flocks on a constant search for food and shelter. They were hunted on a massive scale and sold as cheap commercial food until the last wild pigeon was shot in Ohio in 1900.

The wild passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was once the most abundant bird in North America, numbering perhaps as many as 5 billion individuals. It migrated in enormous flocks on a constant search for food and shelter. They were hunted on a massive scale and sold as cheap commercial food until the last wild pigeon was shot in Ohio in 1900.

In Chainbearer, a novel set after the American Revolution in about 1785 in Upstate New York, James Fenimore Cooper gives this account of a passenger pigeon roost of millions of birds in the Champlain Valley:

I scarce know how to describe that remarkable scene. As we drew near to the summit of the hill, pigeons began to be seen fluttering among the branches over our heads, as individuals are met along the roads that lead into the suburbs of a large town. We had probably seen a thousand birds glancing around among the trees, before we came in view of the roost itself.

The numbers increased as we drew nearer, and presently the forest was alive with them. The fluttering was incessant, and often startling, as we passed ahead, our march producing a movement in the living crowd that really became confounding.

Every tree was literally covered with nests, many having at least a thousand of these frail tenements on their branches, and shaded by the leaves. They often touched each other, a wonderful degree of order prevailing among the hundreds of thousands of families that were here assembled.

The place had the odor of a fowl-house, and squabs [baby birds] just fledged sufficiently to trust themselves in short flights, were fluttering around us in all directions, in tens of thousands. To these were to be added the parents of the young race endeavoring to protect them, and guide them in a way to escape harm.

Although the birds rose as we approached, and the woods just around us seemed fairly alive with pigeons, our presence produced no general commotion; every one of the feathered throng appearing to be so much occupied with its own concerns, as to take little heed of the visit of a party of strangers, though of a race usually so formidable to their own.

The masses moved before us precisely as a crowd of human beings yields to a pressure or a danger on any given point; the vacuum created by its passage filling in its rear, as the water of the ocean flows into the track of the keel…

Not one of our party spoke for several minutes. Astonishment seemed to hold us all tongue tied and we slowly forward into the fluttering throng silent absorbed and full of admiration of the works of the Creator.

Not one of our party spoke for several minutes. Astonishment seemed to hold us all tongue tied and we slowly forward into the fluttering throng silent absorbed and full of admiration of the works of the Creator.

It not easy to hear each others voices when we did speak the incessant fluttering of wings filling the air. Nor the birds silent in other respects.

The pigeon is not noisy creature but a million crowded together on the summit of one hill occupying a space of less than a square mile did not leave the forest in its ordinary stillness…

While standing wondering at the extraordinary scene around us a noise was heard rising above that of the incessant fluttering which I can only liken to that of the trampling of thousands of horses on a beaten road.

This noise at first sounded distant but it increased rapidly in proximity and power until it came rolling in upon us among the tree tops like a crash of thunder. The air was suddenly darkened and the place where we stood as sombre as a dusky twilight.

At the same instant all the pigeons near us that had been on their nests appeared to fall out of them and the space immediately above our heads was at once filled with birds. Chaos itself could hardly have represented greater confusion or a greater uproar…

As for the birds they now seemed to disregard our presence entirely possibly they could not see us on account of their own numbers for they fluttered in between [us] hitting us with their wings and at times appearing as if about to bury us in avalanches of pigeons.

Each of us caught one at least in our hands while Chainbearer and the Indian took them in some numbers letting one prisoner go as another was taken. In a word we seemed to be in a world of pigeons.

This part of the scene may have lasted a minute when the space around us was suddenly cleared the birds glancing upward among the branches of the trees disappearing among the foliage.

All this was the effect produced by the return of the female birds which had been off at a distance some twenty miles at least to feed on beechnuts and which now assumed the places of the males on the nests the latter taking a flight to get their meal in their turn.

—-

Cooper describes The Chainbearer as a surveyor, “the man who carries the chains in measuring the land, the man who helps civilization to grow from the wilderness, but who at the same time continues the chain of evil, increases the potentiality for corruption.”

Read more about the extinction of passenger pigeons.

Illustrations, from above: A depiction of a passenger pigeon hunting in northern Louisiana by Smith Bennett, 1875; and “A Pigeon Net, from an old etching,” in A History of Agriculture in the State of New York by Ulysses Prentiss Hedrick, 1933

Source link