A Sketch of the Great Northern or Champlain Canal, 1822

The following article, “INTERNAL IMPROVEMENT. A Sketch of the Great Northern or Champlain Canal. Waterford, 28th Nov. 1822” was first published in The American Farmer of Baltimore, Maryland, on December 20, 1822.

The following article, “INTERNAL IMPROVEMENT. A Sketch of the Great Northern or Champlain Canal. Waterford, 28th Nov. 1822” was first published in The American Farmer of Baltimore, Maryland, on December 20, 1822.

On this day the last stone of the Northern or Champlain Canal, was laid by Governor Clinton, President of the Board of Canal Commissioners, in the presence of a great assemblage of people.

[A speech by DeWitt Clinton and the invocation of a blessing were included here.]The company passed in two boats [at Waterford], drawn by five elegant horses, from the river through a tier of three locks of white marble and excellent workmanship, into the Canal. The marble was procured from Westchester county, and is firmly cemented by hydraulic mortar, made of Northern limestone.

The locks are of eleven feet lift each, and are almost perfectly water tight. Between the locks there are two spacious circular basins for the accommodation of boats passing out and into the river.

The locks are of eleven feet lift each, and are almost perfectly water tight. Between the locks there are two spacious circular basins for the accommodation of boats passing out and into the river.

Waterford is the head of sloop and boat navigation of the Hudson, and the Northern Canal is now finished to it; indeed it has already been navigated by boats of transportation.

One has just arrived from Lake Ontario, by the St. Lawrence and Sorel rivers, and Lake Champlain; and I saw with great pleasure, packages and boxes, stowed on the banks of the Canal, destined for Whitehall and Peru, in Clinton county.

As the importance of this Canal is not sufficiently appreciated, nor its character extensively known, it may not be amiss to subjoin a few remarks, which I have derived principally from the enlightened acting commissioner.

From Whitehall, where it unites with Lake Champlain, to Waterford, where it finally enters the Hudson River, the distance is about 61½ miles.

From Whitehall to Fort Edward, there are 19 miles of Canal, and about 5 miles of the waters of Wood Creek. In this space there are ten locks: three at Whitehall to let boats down into the Lake; three at Fort Edward for the same purpose, as to the Hudson River; about half way between Fort Edward and Whitehall, to wit, at Fort Ann, there are three locks, which descend to the level of Wood Creek and Halfway Brook.

These streams white [create rapids] below the village, and feed this lower level of the Canal. Some short distance below this junction, there is a lock recently located and made of wood.

The upper level of the canal from Fort Edward to Fort Ann is supplied by the Hudson: the water is impelled into a feeder by a most stupendous dam of 30 feet altitude, erected across that river [in Fort Edward], and there is now another feeder preparing to run from above Glen’s Falls, and to pass into the Canal north of Sandy Hill [now Hudson Falls], which will also serve as an auxiliary Canal, to convey lumber and other commodities from an extensive range of country in that direction.

The upper level of the canal from Fort Edward to Fort Ann is supplied by the Hudson: the water is impelled into a feeder by a most stupendous dam of 30 feet altitude, erected across that river [in Fort Edward], and there is now another feeder preparing to run from above Glen’s Falls, and to pass into the Canal north of Sandy Hill [now Hudson Falls], which will also serve as an auxiliary Canal, to convey lumber and other commodities from an extensive range of country in that direction.

There is a striking feature in the geology of this route, which deserves a scrutinizing examination.

It appears that the Hudson River at Fort Edward, which, you know, is below Glen’s and Baker’s Falls [Hudson Falls], is 22 feet higher than Lake Champlain. There is a descent of 50 feet from the summit level at Fort Ann, to the Lake at Whitehall, and 28 feet to the river at Fort Edward.

Forty or fifty feet high, in the primitive rocks at a place called the Narrows in Wood Creek [near Whitehall], there are great cavities or pots, produced by the action of rotary stones falling perpendicularly: a critical inspection of these lapideous excavations might determine whether the Hudson River did not, previous to its rupture of the great barrier at the Highlands, diverge to the north in this direction.

From the Canal at Fort Edward to Fort Miller Falls, 8 miles, the river is used in lieu of the Canal, and is kept up to the requisite altitude by a dam.

Round those falls there is a short Canal of half a mile, which unites again with the river by two locks; the river is again used for about two and a half miles, and then by a dam it is forced into a canal, on the west side, which extends about 26½ to Waterford.

This contains six locks, and at Waterford there are three more, making in the whole extent 21 locks; 46 miles of artificial navigation, and 15½ miles of improved natural navigation, to wit, five miles of Wood Creek, and 10½ miles of the Hudson River.

From Waterford the Canal proceeds 2½ miles further south, where it unites with the western or Erie Canal, after crossing the Mohawk River by a dam, and which river is thereby put into requisition as a feeder for the northern Canal, in both a northern and southern direction, and also before and after its junction with the western. This latter portion is nearly completed.

The whole extent is 64 miles. The work was commenced on the 10th of June, 1818, and has been finished in somewhat more than four years.

When compared with similar works in the old world, the execution may be pronounced a rapid one, and has never been exceeded in that respect, except by its relative, the western [Erie] Canal.

The celebrated Canal of Languedoc [Canal du Midi, in France] is 148 miles long, it took fourteen years to finish it, and it employed always the labour of 8,000, and sometimes of 12,000 men. The Forth and Clyde Canal [in Scotland] is 35 miles long,. It was commenced in 1768, and not completed until 1790.

The influence of these works is already felt, not only in different parts of the United States, but has extended to Europe.

The transportation of merchandise from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, has fallen from 120 dollars to 40 dollars a ton. When the western Canal is finished, goods can be transported from New York to Pittsburgh for 30 dollars a ton. They formerly cost 100 dollars from New-York to Buffalo. It will now be done for less than 15 dollars.

The receipts of the Holland Land Company have this year been immense, because the western settlers have found a market; and the share holders of our vader-land [fatherland, suggesting the author may be German-American] will be astonished at the unexpected increase of their profits.

In their report of 1817, the Canal Board estimated, that the country within the reach of the northern Canal, would furnish annually two million of boards and planks; one million feet of square timber, and immense quantities of dock logs, scantling, masts, and spars.

Besides, those northern regions are the sites appropriated by nature for her mineral productions; and it is well known that they contain iron ore unsurpassed for quantity and quality; marbles of various kinds and colours; lime stone from the primitive to the secondary, and the materials for the best hydraulic cement; [hemlock] bark for tanning and other manufacturing processes; inexhaustible stores of pot and pearl ashes; wheat, flour, butter, cheese, flax, flax-seed, wool, beef, pork, and maple-sugar; the best of cattle for the butcher, dairyman and grazier, and the finest sheep, hogs, and poultry, besides the fruits of autumn.

Besides, those northern regions are the sites appropriated by nature for her mineral productions; and it is well known that they contain iron ore unsurpassed for quantity and quality; marbles of various kinds and colours; lime stone from the primitive to the secondary, and the materials for the best hydraulic cement; [hemlock] bark for tanning and other manufacturing processes; inexhaustible stores of pot and pearl ashes; wheat, flour, butter, cheese, flax, flax-seed, wool, beef, pork, and maple-sugar; the best of cattle for the butcher, dairyman and grazier, and the finest sheep, hogs, and poultry, besides the fruits of autumn.

In going to the New-York market, the proprietors of these articles follow the current of interest, and the direction of political affinity, and their preference is enforced by the act of the British Parliament, fettering our commerce with the Canada, and thereby imposing the necessity of a limited or partial trade with those countries.

[He refers here to the Navigation Acts, which restricted British trade outside the colonies, of which the United States was no longer one. The principle of enumeration of specific trade goods, which restricted certain goods to English or British ports, was abandoned in 1822, although the the navigation Acts were not repealed until 1849.]We cannot form any definite opinion of the value or the amount of commodities, that will be conveyed down the Canal, nor of the merchandise that will be returned, because it has not been in operation until this day.

So far back as July last [July 1821], it was estimated such was the immense amount of lumber in the Canal and in the Lake, waiting for the advent of the waters, that it would take twenty days for that in the Lake to pass into the Canal, and forty days for that in the lower level to pass into the upper; and the waters of the Hudson are, even at this advanced period of the season, covered with rafts, making their way to our great commercial emporium. – [signed] G. W.

Read more about the Champlain Canal.

This article was located and transcribed by George A. Thompson for the Hudson River Maritime Museum. It has been annotated by John Warren.

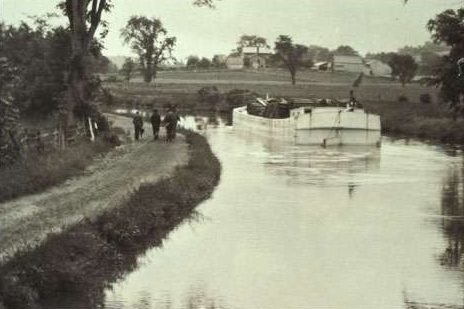

Illustrations, from above: The Champlain Canal, 1895 by Howard Pyle; Lock 10 constructed in 1822, forming an outlet between the old Champlain Canal and the Hudson River (note small lock tender’s shack); Map showing Champlain Lock 15, the Drydock, the Fort Edward Feeder Canal and the waste weir; and Map of the Champlain Canal and its Connections from 1859.

Source link