From Public Hanging to Electric Chair: Kemmler, Edison & Tesla

Italian jurist and criminologist Cesare Beccaria was a leading figure in Milan’s Enlightenment circles. In 1764 he published his treatise Dei delitti e delle pene which made an instant impact. Translated in many languages, an English version appeared in 1767 as On Crimes and Punishments.

Italian jurist and criminologist Cesare Beccaria was a leading figure in Milan’s Enlightenment circles. In 1764 he published his treatise Dei delitti e delle pene which made an instant impact. Translated in many languages, an English version appeared in 1767 as On Crimes and Punishments.

Advocating proportionality of punishment, Beccaria was one of the first thinkers to make a case against the death penalty by claiming that it is “better to prevent crimes than to punish them.”

Insisting that there is no justification for the taking of life by the state, his exposition made a strong impact in Europe and America. Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson acquired a copy of the book in 1769. The latter scribbled more than two dozen passages from Beccaria’s study into his “commonplace book” (a diary of his reading).

When asked by a reporter what would be the greatest challenge to any political career, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan reputedly replied: “Events, dear boy, events.” Incidents happen and tend to knock governments off course or instigate change.

Against the background of Enlightenment thinking, unpredicted events made an impact on the way in which society dealt with crime and punishment, both in London and New York – and there were many similarities.

Tyburn Theater

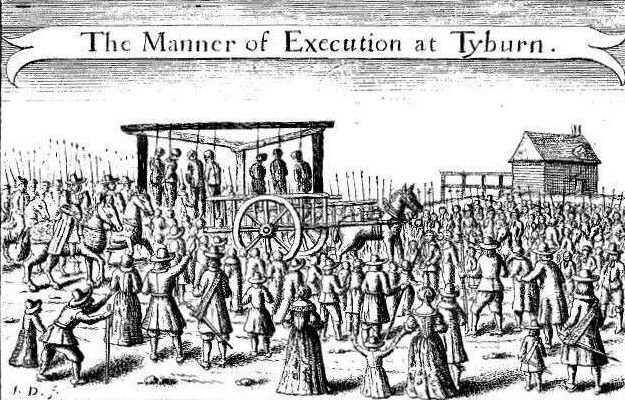

In early nineteenth-century England there were more than two hundred offenses carrying the death penalty, from stealing sheep to treason, arson or murder. Until 1783, Tyburn (a village close to the current location of Marble Arch) served as London’s primary place of execution.

Public display of hangings was a vital part of a legal system that relied upon deterring people from committing crime. Executions were spectacles that followed a regulated protocol. For the occasion to set a fearful example, the “performance” had to be a dramatic one.

Public display of hangings was a vital part of a legal system that relied upon deterring people from committing crime. Executions were spectacles that followed a regulated protocol. For the occasion to set a fearful example, the “performance” had to be a dramatic one.

A public execution was set for three days after trial, allowing time for repentance and reconciliation. The event itself was both ritual and spectacle.

Large numbers of onlookers, men, women and children, enjoyed the atmosphere. It was a family affair and a profitable day for vendors, pickpockets and prostitutes. Printed broadsides were offered for sale telling stories of murderers, pirates, traitors and other felons. Such tales enhanced the excitement.

On hanging day, the condemned person was transported from Newgate Prison to the execution site in a two-mile procession through central London. The journey took place on an open cart and drinks were consumed on the way. The “parade” could last for several hours. A rowdy mob followed the cart, pelting the convicted criminal with rotten vegetables and stones.

The prison chaplain accompanied the criminal (not all, but mostly males) during the procession and on to the scaffold, praying for him. An addition to the process was the “gallows speech.” The spiritual state of those facing death was believed to possess a special truth.

Convention dictated that a felon confessed his sins. In doing so, he accepted the fairness of his sentence and the legitimacy of the justice system.

But convicts did not always adhere to expectations in their final address. Some claimed innocence; others complained of injustices in their conviction. Increasingly, spectators demanded “firework” from the platform.

An outrageous speech electrified onlookers who became vocally involved in this carnival of death. Then the hangman appeared, the noose was adjusted and a bag drawn over the criminal’s head. The horse would be lashed to move the cart and leave the criminal hanging in the air.

Procession and execution would serve, according to Henry Fielding in An Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers (1751), to “add the Punishment of Shame to that of Death; in order to make the Example an Object of greater Terror.”

Procession and execution would serve, according to Henry Fielding in An Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers (1751), to “add the Punishment of Shame to that of Death; in order to make the Example an Object of greater Terror.”

The regularity of hangings however led to execution-fatigue amongst the public and a hardening of moral senses. Around the mid-eighteenth century critics began demanding a stop to public executions.

By 1861 the number of capital offenses was reduced to five (murder, piracy, arson, espionage and high treason). Seven years later, the Capital Punishment Amendment Act was passed, requiring that hangings must be conducted in private.

The last public execution took place on May 26, 1868, when Irish activist Michael Barrett was hanged for his part in the Clerkenwell bomb explosion of December 1867 in which twelve bystanders died.

Hanging John Johnson

When European peoples emigrated to settle in what is now the United States, they brought with them the laws and customs of their homelands. England introduced the death penalty into the American colonies.

The first recorded instance took place in 1608 when Captain George Kendall was executed in Jamestown, Virginia, for plotting to betray the English to the Spanish. He was executed in front of a firing squad.

New York’s history of capital punishment also goes back to colonial times. During various periods from the 1600s onward, its legal provisions prescribed the death penalty for crimes such as sodomy, rape, adultery, counterfeiting or perjury. Most executions were carried out by hanging.

By 1796, the legislature authorized construction of the State’s first penitentiary and reduced the number of capital crimes from thirteen to two (murder and treason, to which arson was added in 1808).

John Johnson was a family man who kept his wife and children at an upstate farm whilst he ran a seedy boarding house for mariners at 65 Front Street, Lower Manhattan, close to the buzzing port.

One day in 1823, the body of a Boston sailor named James Murray was discovered in a nearby alley. His head had been split open with a hatchet.

Murray had rented a room at Johnson’s lodge. When police officers found bloody sheets in the cellar of the property, the latter was accused of robbery and murder. Under interrogation Johnson made conflicting statements, admitting to the crime, then retracting his statement, blaming another guest for the attack.

The case attracted wide publicity. Whether Johnson was fairly treated is unclear, but public interest in the story reached fever pitch as details were splashed across newspapers. Decrying his innocence to the end of the trial, he was sentenced to hang on April 2, 1824.

The case attracted wide publicity. Whether Johnson was fairly treated is unclear, but public interest in the story reached fever pitch as details were splashed across newspapers. Decrying his innocence to the end of the trial, he was sentenced to hang on April 2, 1824.

Seated on a coffin in an open wagon, Johnson was transported from Bridewell Prison through Broadway to a field at the junction of Second Avenue and 13th Street (once part of Peter Stuyvesant’s “Bouwerie”). He was accompanied to the gallows by a minister and escorted by infantrymen who had to hold back an over-excited pack of onlookers.

His hanging was witnessed by a huge crowd. Estimates vary between thirty and fifty thousand spectators which, at the time, was almost a third of New York City’s entire population.

His body was then taken to the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Barclay Street, Manhattan, where it was subjected to a number of medical “experiments.”

Public Executions

Wherever they took place, public executions were unruly affairs, achieving the opposite of their intended effect. Instead of deterring people from crime, these events were an orgy of drunkenness debauchery and pick-pocketing. There were many observers who called for a stop to public hangings on moral grounds.

The city authorities seemed to agree – but for an entirely different reason. The execution of John Johnson had caused gridlock conditions in Manhattan. His macabre death marked a change in decision making.

Future executions were to be moved to nearby Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island) where crowds would not be able to reach proceedings. The outcome proved even worse. Nothing could deter the mob from entertainment.

On May 7, 1829, the double execution of convicted murderers Richard Johnson (a white man) and Catharine Cashier (a Black woman), was to take place on the island.

On May 7, 1829, the double execution of convicted murderers Richard Johnson (a white man) and Catharine Cashier (a Black woman), was to take place on the island.

That day The Evening Post reported that large crowds had gathered outside Bridewell Prison at an early hour. Broadway was “blocked up with spectators, so much so as to make it difficult for carriages to pass; and for a short time before the procession moved, every avenue leading to the prison was completely closed.”

The prisoners were supposed to have been moved quickly to the port where a chartered steamer awaited them, but several delays allowed a huge crowd to build up. There was worse to come.

When the ship left dock, thousands of spectators had piled into small vessels and ringed the island. Many made their way ashore. This time gridlock prevailed on the East River.

Regular water traffic was brought to a halt, whilst steamboats packed with spectators jostled for the best vantage point. At least three small vessels overturned and a number of people drowned.

It turned out to be one of the last public executions staged in the city of New York. The council ordered that all future hangings would take place in prison behind closed-doors. Only a select number of people were allowed to attend proceedings.

Final Event

The final public execution in the City took place on July 13, 1860. Sailor and lifelong petty criminal Albert Hicks had joined a three men crew of the E.A. Johnson, a sloop docked on the Hudson River which he knew to be carrying cash for buying oysters in Virginia.

When the vessel approached Staten Island, he grasped an axe, killed his colleagues, stole all money and valuables, and reached the shore in a small rowing boat. When coast guards entered the abandoned and blood-bathed sloop, they just found mutilated body parts.

After a huge manhunt, Hicks was arrested at a boarding house in Providence, Rhode Island, where detectives recovered some of the stolen goods. He was returned to Manhattan and tried for piracy in a Federal Court.

The case created a sensation. Public executions were proscribed by New York State by then, but the federal government had no such ban. New Yorkers wanted Hicks to hang. He was taken to Bedloe’s Island to be executed.

The case created a sensation. Public executions were proscribed by New York State by then, but the federal government had no such ban. New Yorkers wanted Hicks to hang. He was taken to Bedloe’s Island to be executed.

Having undergone a religious conversion in prison, Hicks stepped calmly towards the gallows as if resigned to his fate. He was smartly dressed, wearing his favorite wide-brimmed Kossuth hat down low of one eye. An estimated 12,000 rowdy spectators had turned up to view the display from boats anchored in New York Bay.

Hicks made no gallows speech. Kneeling down for a brief prayer, he spoke his last words. “Hang me quick – make haste.”

The hangman slipped a hood over his head, placed a rope around his neck and pulled the lever. When the weights dropped, Hicks was thrown six meters into the air, his neck snapping at the third vertebra.

The crowd cheered. A quarter of a century later, Bedloe’s Island (renamed Liberty Island in 1956) became home of the Statue of Liberty.

The public spectacle of official physical punishment disappeared from legal proceedings in the aftermath. The word “punish” itself became suspect. The renaming of institutions was evidence thereof.

The slammer became a penal institution; prison was turned into a house of correction. The new name was a euphemism in order to expel memories of a brutal past. Metaphorically at least, it suggested a more humane regime.

Humane Methods

Physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin was one of ten Parisian deputies in the French Assembly and an advocate of prison reform. In October 1789 he proposed that capital punishment should take place by means of a “painless” mechanism as a first step towards the abolition of the death penalty altogether.

While he did not invent the guillotine, the politician’s name became an eponym for it. He also vowed to make punishment a more private process, but the public was not convinced. A “hidden” execution was considered suspicious.

While he did not invent the guillotine, the politician’s name became an eponym for it. He also vowed to make punishment a more private process, but the public was not convinced. A “hidden” execution was considered suspicious.

The first time that the guillotine was applied, the Chronique de Paris reported widespread protests and calls for “Give us back our gallows.”

Nearly a century later (1886), New York State established a committee to determine a less cruel system to replace hanging. Dentist Alfred Southwick came up with the idea of putting electric currents through a chair.

A prototype was built by employees of Thomas Alva Edison’s works at West Orange, New Jersey. Edison suggested that the system of alternating current (AC) system, developed by his arch-rival, Serbian-born engineer Nikola Tesla, be applied to for its superior lethal power.

The first person to be executed in this manner was William Kemmler at New York Auburn Prison on August 6, 1890. He descended from a dysfunctional family of German immigrants; William himself was notorious for drinking binges in his Buffalo neighborhood. He murdered his wife Tillie Ziegler with a hatchet.

On the morning of his execution, Kemmler was presented to seventeen witnesses in attendance. The first passage of current through his body lasted seventeen seconds. It caused unconsciousness, but failed to stop his heart.

The generator was re-charged and in a second attempt William was shocked with 2,000 volts. Blood vessels ruptured and his body caught fire. The stench in the death chamber “was unbearable,” according to a report in The New York Times.

The generator was re-charged and in a second attempt William was shocked with 2,000 volts. Blood vessels ruptured and his body caught fire. The stench in the death chamber “was unbearable,” according to a report in The New York Times.

The entire process took eight minutes. Those present described the execution as a grotesque and shocking spectacle, one far worse than hanging.

The botched nature of the act in addition to the disputed legal proceedings leading up to Kemmler’s execution caused widespread concern and would contribute to the rise of movements that pleaded for the abolition of capital punishment altogether.

After examining Kemmler’s body, Tesla declared that death by electrocution was “cruel torture” and that the chair should never be used again.

Read more about crime and justice in New York.

Illustrations from above: Detail of portrait of Cesare Beccaria by Jean-Baptiste-François Bosio, nd (Metropolitan Museum of Art); Contemporary image of a Hanging Day at Tyburn, London; An Enquiry Into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers; H. R. Robinson, “Old Bridewell, Manhattan”; A Correct Copy of the Trial and Conviction of Richard Johnson (New York); “Hicks the Pirate,” a murder ballad by H. S. Backus (sung to “The Rose Tree”); Prototype of the first electric chair, 1890; and a contemporary illustration of Kemmler’s execution.

Source link