The Hidden World of Carnivorous Fungi

In darkness, a wormlike creature squirms. A tiny nematode weaves its way between grains of rock and particles of organic matter, through inverted forests of tree roots. It follows what it thinks is a pheromone trail, pausing to inspect a droplet poised on the tip of a pale, nondescript strand of fungus.

In darkness, a wormlike creature squirms. A tiny nematode weaves its way between grains of rock and particles of organic matter, through inverted forests of tree roots. It follows what it thinks is a pheromone trail, pausing to inspect a droplet poised on the tip of a pale, nondescript strand of fungus.

A moment later, its body begins to seize up. The chemical signals that control its muscles have been hijacked, and within seconds it is completely paralyzed.

Soon, new strands begin to grow from the nearby fungal hyphae. They snake toward the nematode. Slowly, inexorably, filaments pierce its flesh and begin to dissolve the worm from the inside out, feeding the nutrients back into a network of fungal tissue.

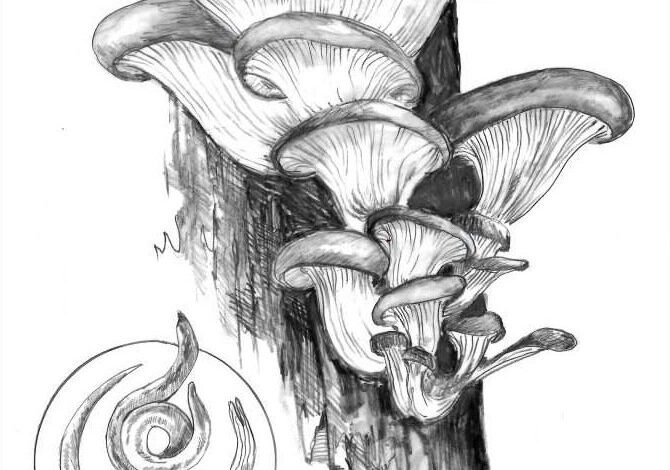

Some time later, a ladder of ivory-colored mushrooms erupts from the side of a nearby stump. These are oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), a familiar fungus often found on beech trees, and one of about 700 known fungi with a penchant for carnivory.

A few are well-known mushrooms, like oysters and the lawn-loving shaggy ink cap (Coprinus comatus), but most remain hidden away in dirt, leaf litter, or rotting wood, known only to mycologists.

Yet every major lineage of fungus has produced some species capable of consuming the minuscule animals that occupy nearly the entire surface of the earth.

Nematodes make up the majority of this micro-zoo; the Global Soil Biodiversity Initiative estimates there are 60 billion soil nematodes for every single human. Carnivorous fungi have amassed a ghoulish bag of tricks to enrapture, entrap, and impale these creatures.

Many produce sticky tissues, in configurations ranging from nets to rings to knobs. Nematodes that make contact are glued in place long enough to be consumed. These fungi often improve their odds with chemical lures that mimic the signals nematodes use to communicate.

Other species produce tiny nooses that are not sticky, but sensitive. When something touches the inside of the loop, they triple in volume in a tenth of a second, squeezing shut like a deadly inflatable doughnut. Still others, like the oyster mushroom, use poisons.

The contentious relationship between fungi and nematodes has deep roots.

A 2021 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by researchers from Academia Sinica in Taiwan tested oyster mushrooms and found that their toxin was effective against 11 different genera of nematode, including some separated by at least 280 million years of evolution.

Over millions of years, the ability to consume nematodes has evolved multiple times independently, implying a strong adaptive advantage to having this ability.

The reason for carnivory in fungi is the same as for plants: limited soil nutrients. In the Northeast, carnivorous pitcher plants and sundews are found in the acidic and nitrogen-poor soil of bogs. What bogs lack in nutrients, they make up for in bugs.

Likewise, nematode-eating fungi tend to be found in low-nutrient environments. But unlike plants, these fungi won’t deploy their traps unless they’re lacking essential nutrients or detect nematodes in their environment – preferably both.

Experiments conducted in 1964 by David Pramer at Rutgers University showed that adding “nematode extract” to cultivated fungi of the saprophytic (decomposing) species Arthrobotrys conoides could induce the formation of traps, demonstrating fungi’s ability to chemically sense the presence of nearby nematodes and respond accordingly.

The nematode-busting abilities of fungi have caught the attention of farmers and foresters. One widely cited estimate predicts more than $150 billion in lost crop productivity worldwide due to nematode activity.

In our woodlands, beech leaf disease is associated with an introduced nematode species, and our native pinewood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus) causes pine wilt when it infects cultivated foreign plants like Scots pine, and could be potentially disastrous if brought overseas.

Using fungi as alternatives to environmentally fraught chemical nematocides is an area of active research.

In the meantime, the next time you sauté up some freshly foraged oyster mushrooms, spare a thought for the nematodes that may have given their lives.

Read more about New York State fungi.

Kenrick Vezina is a freelance writer, naturalist, and raconteur based in the Greater Boston area. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.

Source link