The Beaver Quest: Pelts & Testicles

In 1609, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) sent navigator Henry Hudson westward to discover a short route to Asia. Instead, he reached the river that today bears his name, finding a biologically rich and diverse ecosystem.

In 1609, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) sent navigator Henry Hudson westward to discover a short route to Asia. Instead, he reached the river that today bears his name, finding a biologically rich and diverse ecosystem.

On his report (published in 1611) of timber rich lands and an abundance of furs, Dutch traders were keen to finance further exploration.

In October 1614, a group of merchants formed the New Netherland Company and received a three-year monopoly from the States General – the de facto federal government of the Dutch Republic – to gain a foothold and exploit the region.

In 1615 the Company erected Fort Nassau on Castle Island, five miles south of the confluence of the Mohawk and Hudson Rivers, and began the trade in beaver fur with Native Americans.

(The island at what is now Albany, was later known as Marte Gerrite’s and then Westerlo Island.)

At the end of its term the contract was not renewed, but Dutch traders remained active in the area and the quest for beavers continued. In 1621, after years of private exploration, the States-General created the West India Company (WIC).

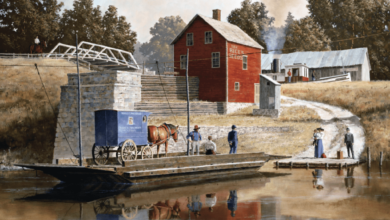

In 1624, the WIC made its first attempt at establishing a permanent trading presence on the same spot where the earlier Fort Nassau had been damaged by flooding. They named the new outpost Fort Orange. The community that grew around it came to be known as Beverwyck.

The Company held a monopoly on fur trading and in order to keep it legislation required all commercial dealings occur at the fort and furs be transshipped through Manhattan Island. Between 1626 and 1632, some 52,584 beaver pelts were shipped to the Netherlands.

Dutch involvement in Manhattan’s beaver fur trade provided the economic impetus for the establishment of the New Netherland colony and the foundation of New Amsterdam.

The beaver’s significance to the settlement was demonstrated by proposed designs for the coats of arms for New Amsterdam and New Netherland.

The beaver’s significance to the settlement was demonstrated by proposed designs for the coats of arms for New Amsterdam and New Netherland.

In 1630, three drawings by an anonymous artist were presented for approval to members of the WIC’s ruling council in Amsterdam. They all featured the beaver prominently positioned as part of the colony’s identity.

These historical facts are well known and widely shared. Less clearly explained is the European obsession with beaver fur.

Why did Dutch, Flemish and Walloon settlers scramble for unfamiliar and dangerous territory competing with English and French rivals to trap a rodent?

Miracle Cure

Beavers once inhabited an extensive area from Western Europe to the Sino-Mongolian border. By the seventeenth century, they had been hunted to near extinction in Russia and Sweden. Beavers were trapped for meat and chased not only for their furs and pelts, but also for their alleged medicinal properties.

The Eurasian beaver had played its part in ancient and Roman culture. The vegetarian animal has a gland under its tail that secretes a urine-based substance called castoreum (“castor” is the Latin word for beaver) which is used for scent-marking.

This particular chemical was valued for its medicinal properties which has been credited to salicin, a natural compound from willow bark in the beaver’s diet which, transformed to salicylic acid, is a major component in aspirin.

Based on the teachings of the Greek physician Hippocrates, the Hippocratic Corpus dating from around the fourth century B.C. cites beaver testicles in the context of various ailments.

Castoreum was used to treat epilepsy, nervous disorders, colic, poisonous scorpion stings and toothaches. The yellowish fluid continued to be praised for its healing powers.

In 1652, English physician Nicholas Culpeper published The Complete Herbal, a rich source for the study of pharmaceutical practice at the time.

He paid ample attention to castoreum as it “resists poison, the bitings of venomous beasts; it provokes the menses, and brings forth birth and after-birth; it expels wind, eases pains and aches, convulsions, sighings, lethargies; the smell of it allays the fits of the mother; inwardly given, it helps tremblings, falling-sickness, and other such ill effects of the brain and nerves.”

Such passages seem to reflect a sense of desperation about the state of medicine. Epidemics were stalking the cities and disease spread quickly.

Death was everywhere and people died young as there were no effective cures for infections or epidemics of flu, cholera or diphtheria. Europe was in search of a “miracle cure.”

Castration Myth

To harvest castoreum, trappers killed beavers and removed their castor glands which were dried and crushed. In raw form its scent has been described as resembling “birch tar or Russian leather,” but when diluted in alcohol it smells entirely different.

Some of its molecules are structurally similar to vanillin, the compound in vanilla orchids. Beaver secretion was applied in perfumery, soap and food flavorings.

According to Roman authors the best quality castoreum was imported from the Pontus region, an ancient district in north-eastern Anatolia (Turkey) adjoining the Black Sea and later a Roman province.

Pontus was associated with beaver testicles. Having grown into a parasitical consumer city, Rome could not import enough stocks edicines and perfumes. Within a relatively short time, the beaver population plummeted.

When in the first century A.D. the Roman author Pliny the Elder took to writing his Natural History, a “proto-scientific” compendium on all thing’s natural, beavers had become almost extinct.

He had probably never seen a beaver in the wild and relied on past testimonies. Without the check of first-hand observation, he let his imagination run free.

Pliny circulated what would become a famous legend: “The beavers of Pontus cut off these same parts [their testicles] when danger presses, knowing that this is why they are hunted.”

He perpetuated one of Aesop’s fables (no. 118): “When pursued, the beaver runs for some distance, but when he sees he cannot escape, he will bite off his own testicles and throw them to the hunter, and thus escape death.”

The legend lived on in medieval bestiaries (collections of short descriptions about all sorts of animals, real and imaginary) in which beavers are always depicted the same manner: on the run being pursued by a hunter and dogs.

The legend lived on in medieval bestiaries (collections of short descriptions about all sorts of animals, real and imaginary) in which beavers are always depicted the same manner: on the run being pursued by a hunter and dogs.

The tale of self-castration was adopted by the Christian Church and modified. The beaver’s plight was turned into a lesson on adultery and morality.

The relentless pursuit and eventual near extinction of a vulnerable rodent was mythologized and given the status of fiction. It was not until 1646 that the tale was busted as a “vulgar error.”

London-born scientist and polymath Thomas Browne pointed out in his Pseudodoxia epidemica (Vulgar Errors) that the beaver’s “eunuchate or castrate” habit was simply not possible as his testicles were located inside the body.

Devastation

Reports that beavers seemed in boundless residence in the forests of North America caused a stir in Europe. Beaver pelts (“soft gold”) and other furs were initially imported from Russia.

In the early seventeenth century the beaver population throughout northern Europe and Siberia became severely depleted due to over-hunting. By 1600, nearly all fur exports from Russia had stopped.

This exhaustion of beaver populations coincided with the arrival of European settlers in North America. As there were no physical differences between the North American (Castor canadensis) and the Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber), the potential of rich supplies opened up once more. Hence the rush of Dutch and Flemish entrepreneurs to establish trade relations with Native Americans.

Lawyer and landowner Adriaen van der Donck (ca. 1618 – 1655) had resided for a decade in present-day Albany before conflicts with Governor Peter Stuyvesant prompted his return to Amsterdam.

Lawyer and landowner Adriaen van der Donck (ca. 1618 – 1655) had resided for a decade in present-day Albany before conflicts with Governor Peter Stuyvesant prompted his return to Amsterdam.

In 1655, he published the best contemporary account of the colony, entitled Beschryvinge van Nieuw-Nederlant (Depiction of New Netherland), with the aim of presenting an image the colony as an enticing destination for emigrants.

In his narrative the author did not focus on the colony’s conquest and foundation. His book is an ethnography of indigenous populations, a natural history and a cartography of resources. Divided into four chapters, the third is dedicated to the “Nature, Amazing Ways, and Properties of the Beavers.”

Van der Donck argues here that the beaver provided basic survival necessities (food and warm fur). He also suggested that medicinal properties derived from beaver parts offered a cure for many illnesses and was therefore of interest to medical research in Europe.

He emphasized similar curative “blessings” of castoreum as Culpeper had set out in his herbal three years previously. The author claimed that beaver oil cured rheumatism, toothaches, stomach aches, poor vision and dizziness; beaver testicles rubbed on the forehead or dried and dissolved in water made an effective antidote to drowsiness and idiocy.

Van der Donck tried to convince his readers that the beaver offered security to settlers in New Netherland, but the reality by the mid-seventeenth century was different.

Due to the elusive and aquatic nature of beavers, settlers found them difficult to locate and trap. Contacts were made with native tribes to seek their hunting expertise and exchange pelts for goods manufactured in Europe (axe heads, knives, jewelry, glass beads, ammunition, alcohol and other items).

Colonial settlement upset the traditional status quo amongst indigenous populations. The European craze for furs helped cause local populations to devote more their energy to hunting and trapping and to move farther afield in an effort to increase catches. This, in turn, had a devastating effect on the beaver and its habitat.

The Dutch and Iroquois formed an alliance for the supply of beavers. They over-hunted its population and as early as 1640 beavers began to disappear from the Hudson Valley.

The Iroquois then sought to expand their hunting ground to the north and west around the Great Lakes and into Canada, leading to bloody territorial conflicts. The Beaver Wars lasted more than seventy years.

Felt & Fashion

As for certain groups within European society standards of living rose, fashion began to determine dress and costume. Fur-lined coats, fur collars, capes and muffs became voguish. The beaver was prized because its fur had a special characteristic: under the coat it carried a layer of short, tightly-packed hairs which was turned into felt.

All over the Continent, felted beaver hats had

been in demand from at least the mid-fourteenth century and were a status symbol as evidenced by Geoffrey’s Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales where the author refers to a merchant wearing a “Flandrish [Flemish] beaver hat.” Their manufacture was a Huguenot specialty.

been in demand from at least the mid-fourteenth century and were a status symbol as evidenced by Geoffrey’s Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales where the author refers to a merchant wearing a “Flandrish [Flemish] beaver hat.” Their manufacture was a Huguenot specialty.

Hat making developed in Normandy during the period that the Edict of Nantes (1598 – ca. 1630s) was in force, allowing French Protestants to live and worship in peace.

The industry flourished in Caudebec-en-Caux, a town close to Rouen on the right bank of the River Seine. Made from beaver hair and felted in a protected secret process, “Caudebec” hats were waterproof – a unique and unrivaled achievement at the time.

The costly “Huguenot” beaver hat was worn at the Royal Court, by the Catholic clergy, or by Ashkenazi Jewish men (mainly members of Hasidic Judaism). Felt hats reflected social identity and rank.

From Catholic Cardinal to Puritan Minister, from army officer to local official, every hat carried a specific set of meanings. The felt hat was a visual statement about one’s communal status. The demand for beaver pelts was enormous.

In 1600, there may have been as many as a hundred million beavers in North America. The conquest of the continent had been driven by a desire for pelts that the forests of Europe and Asia could no longer satisfy. The American beaver population decreased dramatically as a result of the European fetish for luxury goods.

What eventually saved the animal was both progress in medical research and a change in European fashion. Beaver hats went out of style during the 1700s as the silk top hat gained in popularity.

It was a plenitude of beavers that motivated the Dutch and Flemish to create settlements in Lenapehoking (Land of the Lenape) and establish New Amsterdam at the tip of Manhattan. From the outset, the project had been a commercial venture for the WIC.

It is no coincidence that the Company’s willingness to negotiate its withdrawal from the region coincided with a sharp decline in beaver populations on the island. They had been hunted down mercilessly and trapped to near extinction.

In 1664, New Amsterdam was reincorporated under English law as the City of New York. Six years later, the British chartered Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), establishing its fur business throughout North America and Canada, monopolized the trade.

The company retained that dominating economic position until the arrival of John Jacob Astor (1763-1848), a German-speaking immigrant from Walldorf (near Heidelberg).

The company retained that dominating economic position until the arrival of John Jacob Astor (1763-1848), a German-speaking immigrant from Walldorf (near Heidelberg).

Having settled in the City he started work for the Quaker merchant Robert Bowne, learning the business of buying and selling furs.

Astor founded the American Fur Company in 1808. By 1830, he controlled the nation’s entire fur trade, using his profits to buy huge tracts of land in New York.

Fur is the real tale of the metropolis. It motivated the Dutch to build New Amsterdam and enabled Astor to spend a fortune on real estate investments that would transform New York’s cityscape.

Read more about beavers in New York State.

Illustrations from above: Len F. Tantillo’s “Fort Orange, 1635” (in a private collection, provided by NYS Museum); Proposed coats of arms for New Amsterdam and New Netherland prepared by an anonymous artist in 1630 for consideration by the WIC; A thirteenth-century manuscript illustrating a hunted beaver castrating itself (from the Salisbury Bestiary); detail from a map showing Fort Orange and known Upper Hudson River area in Adriaen van der Donck’s Beschryvinge van Nieuw-Nederlant [Depiction of New Netherland], 1655 (Library of Congress); a selection of “professional” beaver hats; and John Jacob Astor, founder of the American Fur Company.

Source link