Cattle Drives in New York State: Some History

Cattle drives have had an enormous impact on popular culture. The cowboy is a uniquely American icon that came to be widely admired and imitated in sensational newspaper reports, cheaply produced books and later in motion pictures and television shows.

Cattle drives have had an enormous impact on popular culture. The cowboy is a uniquely American icon that came to be widely admired and imitated in sensational newspaper reports, cheaply produced books and later in motion pictures and television shows.

Driving cattle across great distances was not something found only in the western states however, up until the mid-1850s New Yorkers organized cattle drives too.

Before “The West”

Spaniards established the ranching industry in the New World and had begun driving herds of cattle in the 1540s. Later herds of cattle were driven from northern Mexico (Coahuilay Texas, Nuevo Mexico, and Alta California, what we would call “The American West”) into Louisiana.

The Chisholm Trail and the Great Western Trail were the two most heavily used of a network of trails that Texas ranchers and contractors used to move cattle from the early 1850s through the late 1880s from Texas to various Midwestern and Great Plains states.

Historians have identified more than a score of major trails that emerged, witnessed the passage of cattle herds, and faded during that time.

The Shawnee Trail, the Chisholm Trail, the Western Trail, and the Goodnight-Loving Trail moved north. In 1853 the Italian aristocrat Leonetto Cipriani made large profits driving cattle west from St. Louis to San Francisco along the California Trail.

Relatively long-distance herding of hogs was also common. In 1815 Timothy Flint “encountered a drove of more than 1,000 cattle and swine” being driven from the interior of Ohio to Philadelphia.

Most cattle driving routes in the United States were shorter, and most utilized existing trails and roads. For example, in the early 19th-century Pennsylvania cattle drovers brought their herds to Philadelphia on the Conestoga Road and Lancaster Pike.

In the East, the cowboys were known as “drovers.” They rode the countryside buying cattle, pigs and other livestock, and driving them to market.

Uncle Sam and Daniel Drew

During the War of 1812, Samuel and Ebenezer Wilson were engaged in an extensive slaughtering business near Troy, employing about one hundred men, and slaughtering more than a thousand head of cattle a week. Those arrived by New York’s growing road network.

Daniel Drew (1797-1897) began building his fortune with a successful business driving cattle after the War of 1812 the 50 miles or so from Putnam County into New York, as described by a contemporary:

“His first ventures lay in near trade with adjacent counties in New York, but he and his partners gradually extended their field, first into Pennsylvania, afterward into the great west.

“His first ventures lay in near trade with adjacent counties in New York, but he and his partners gradually extended their field, first into Pennsylvania, afterward into the great west.

“They brought the first large drove of cattle that ever crossed the Alleghanies – two thousand head – in droves of one hundred each… The cattle were purchased in the valleys of Ohio and Kentucky, paid for in cash, collected in droves, and then brought over by careful hands.”

“The transit required nearly two months, and cost $12 per head, with allowance also of $12 for beef “driven off” in the journey.”

In 1820 he moved to the city of New York and bought the Bull’s Head Tavern, a popular drovers tavern and auction place in the Bowery, once a Lenape footpath running north and south through most of Manhattan Island.

The Dutch called is Bouwerie road – “bouwerie” being an old Dutch word for “farm.” Formerly the Bull’s Head had been owned by Henry Astor, “King of the Butchers” and brother of John Jacob Astor.

By 1825, estimates of the number of cattle driven to the New York market each year ranged as high as 200,000. By then the city had engulfed the Bowery butcher district and it became something of a nuisance.

The old Bull’s Head was torn down and the Bowery Theatre built in its place. A new drover and butcher’s marketplace opened in May, 1825 at the new Bull’s Head, at Third Avenue and Twenty-fourth Street.

Cattle from the west, upon arriving by ferry from New Jersey, had to pass through the city’s streets to get there, an increasingly frequent spectacle as trans-Allegheny drives multiplied in the 1830s.

“Many old New Yorkers will recall the cattle sales of those days and the picturesque features of a locality which is now one of the busiest, noisiest and most populous in the city,” New York George Smith told the New York Herald in 1891, adding:

“Instead of the din of an elevated steam railway and the rattle of innumerable trucks and wagons over the hard stones there were the lowing of great herds and the whispering of spring breezes through the blossoming trees.

“Drovers and butchers, big of limb and carrying enormous whips, drove their own teams to the scene of their transactions and discussed the prospects of trade over foaming glasses in the tap room of the Bull’s Head Hotel.

“Few of them dreamed, doubtless, that another generation would see their cattle yards wiped out in the onward rush of a great city’s life.”

Life of a Drover

Being a drover was adventurous, arduous, and risky – but a good profit was to be had in bringing meat on the hoof to growing eastern markets before the advent of canals, steamboats and railroads.

Drovers could start with small capital buying a handful of small animals and slowly work themselves up to larger animals, larger herds, and a couple hired hands.

The drovers worked in the spring and fall to avoid the heat of summer, which could sweat money from their charges. Each night the stock were pastured at inns or taverns or ‘drove stands’ that could accommodate the men and their charges.

Here drovers and their hands watered their livestock and liquored themselves. They grabbed a meal and some sleep before an early rise and a return to the road.

Here drovers and their hands watered their livestock and liquored themselves. They grabbed a meal and some sleep before an early rise and a return to the road.

Drovers shunned the tolls of the turnpikes, and took back-roads, which were softer on the hoof and less crowded. In dry weather each herd could create choking clouds of dust moving down the road.

“Besides the cattle men, there were grimy pig pelters, aristocratic horse drovers, emigrant families jammed with their belongings in canvas-covered wagons heading west, and sweaty teamsters riding beside laden wagons,” according to one historian.

“I can remember seein’ the herds of cattle [in the 1830s] comin’ along the roads from northern parts to be stocked in the pens. Sometimes you could tell they were coming by the clouds of dust they raised,” William Doubleday remembered in 1886.

“Soon you could hear their bellowings and the shouts of the men driving them, and finally you could see them coming down the road, looking this way and that, as if for some way of escape from the death that was in store for them. I was exciting, I can tell you.”

The reality of a drover’s life on the road was less romantic; it meant long hours, exposure to extreme weather, fording swollen rivers, the potential for stampedes and other dangers of handling 800 to 1,000-pound beef cattle.

There was a minimum of comforts, and low pay, much of which might be spent in a few nights in town at the end of a drive.

For example, in 1858 a wealthy Kentucky cattle drover “was induced” to enter the gambling house in Broadway in New York “by some ‘ropers in,’ into whose clutches he chanced to fall. Hibler, after entering the den, partook of refreshments, after which he was persuaded to take a hand at ‘Faro,’ and at one sitting of six hours, he lost a negotiable check for $600, besides $230 in cash.”

End of the Drovers

During the Panic of 1837, Daniel Drew largely gave up cattle driving to focus on the emerging steamboat business. His retreat from the business could be said to have marked the beginning of the end of the drover.

Sailed sloops had not been well designed for cattle transport, but the canal, steamboats and railroads were quickly utilized to ship larger numbers of cattle to markets and slaughterhouses which were already well established near communities.

In 1830 the Swiftsure Line of Tow Boats reported that “Merchandise, produce, carriages, horses, cattle, and almost every description of live stock, will be forwarded with safety and expedition,” twice a week anywhere between Troy and New York.

The Erie Canal and Champlain Canal had facilitated this decline, but the steam-tows and the railroads sealed the fate of the old time cattle drives in New York.

An observer noted that where it had taken two months in the 1820s, by 1860 “cattle are brought even from Illinois in five or six days. The business of the old-time drover is extinct. The cars and steamboats bring thousands of four-footed passengers a day into the great metropolis.”

Before the Civil War the market at the Troy-Lansingburgh border was among the largest cattle centers of the country, producing meat shipped as far as New York. “The cattle of the entire fertile Mohawk valley sooner or later found its way to Troy,” a local writer remembered.

As with New York, the Lansingburgh municipal cattle market was situated at a tavern known as the “Bull’s Head.” It was located at foot of what is now Glen Avenue, with stockyards and slaughterhouses extending north into Lansingburgh and east to the escarpment; by 1870 it was all gone.

In their place came the great western rail-yards, the cattle towns and cowboys, and the Chicago slaughterhouses and meatpacking industries.

Read more about New York agricultural history.

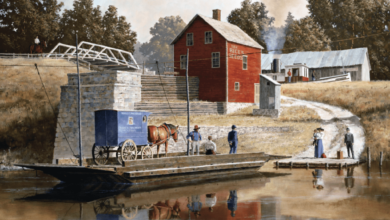

Illustrations, from above: Detail from Asher Durand’s “Progress (The Advance of Civilization),” 1853, showing a cattle drive (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts); “The Thirsty Drover” by Francis William Edmond, ca. 1856; and a painting of the Bull’s Head Tavern on the Bowery in Manhattan, ca. 1783.

Source link