Ventriloquism & America’s First Modern Public Libraries

New York-born John Bigelow started his career in 1849 as co-owner with William Cullen Bryant of the New York Evening Post. In 1861, President Abraham Lincoln appointed him Consul in Paris and promoted him to American Ambassador four years later.

New York-born John Bigelow started his career in 1849 as co-owner with William Cullen Bryant of the New York Evening Post. In 1861, President Abraham Lincoln appointed him Consul in Paris and promoted him to American Ambassador four years later.

His diplomatic efforts were aimed at influencing the French in favor of the federal government. Working with Charles Francis Adams, U.S. Minister to the United Kingdom, he blocked political attempts to have France and Britain intervene in the Civil War on behalf of the Confederacy, thus paving the way for the United States victory.

Diplomat & Ventriloquist

Bigelow returned to the city of New York after the Civil War and, in 1868, published an edition of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, based on an original but unfinished manuscript. Since the document ended in the year 1757, Bigelow extended this work in 1874 into a three-volume Life of Benjamin Franklin, incorporating Franklin’s extensive correspondence.

Having met up with his old friend Samuel Jones Tilden (the 25th Governor of New York), Bigelow was elected Secretary of State of New York in 1872. When four years later the Democrats nominated Tilden as their presidential candidate, he served as his campaign manager and advisor in the controversy over the election’s result. The bitter dispute was decided in favor of Tilden’s Republican rival, Rutherford Birchard Hayes.

Having abandoned politics, Tilden died a decade later. Bigelow acted as one of his executors and carried out Tilden’s final wish for the establishment of a free public library and reading-room in the City of New York.

Having abandoned politics, Tilden died a decade later. Bigelow acted as one of his executors and carried out Tilden’s final wish for the establishment of a free public library and reading-room in the City of New York.

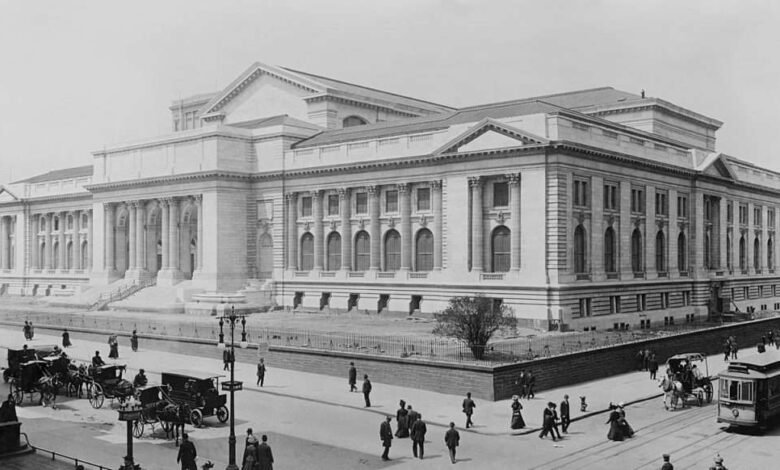

In 1895, the Tilden Trust joined with the Astor and Lenox libraries to establish the New York Public Library (NYPL). Bigelow served as its first President until his death in December 1911. In 1895 he published a tribute to his friend in the two-volume Life of Samuel J. Tilden.

When Bigelow served as American Consul in Paris, news broke in 1864 of the death of a “lost” French friend named Nicolas-Marie-Alexandre Vattemare. When the impoverished heirs put the latter’s papers up for auction, Bigelow acquired the material that he considered of value to students of early American history.

Decades later he presented the collection as a gift to the NYPL. Today, the “Alexandre Vattemare Papers” are held in its Manuscripts and Archives Division (portions of which have been digitized and are available online). Who then was Alexandre Vattemare?

Born in Paris in 1796, he was the son of a wealthy lawyer who descended from minor French nobility. In this tumultuous era preceding the French Revolution, his father took the family away from the capital and settled on a small estate at Lisieux in rural Normandy.

At a young age, Alexandre discovered that he could make his voice speak as though sounds emerged from outside his body. He also had an ability to imitate all manner of sounds, be they human, animal or mechanical, playing practical jokes on family members, neighbors and locals.

His natural talent for ventriloquism (“speaking from the belly”) may have worried his parents as the ability was loaded at the time with a negative reputation and associated with demonic possession. Illusionary tricks being condemned as evil acts, ventriloquists were shunned for their perceived diabolical connections. Alexandre was sent to a provincial seminary to prepare (and restrain) him for the priesthood.

Unable to conform to the rules of the institution, he was expelled and then attended a medical school at the Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris. Although an excellent student, becoming a surgeon’s assistant at sixteen, he maintained a streak for insubordination and an eagerness to play pranks.

![An engraving from 1806 showing ”Edw[ar]d Kelly, a Magician in the Act of invoking the Spirit of a Deceased Person”](https://www.newyorkalmanack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/An-engraving-from-1806-showing-Edward-Kelly-a-Magician-in-the-Act-of-invoking-the-Spirit-of-a-Deceased-Person-232x300.jpg)

![An engraving from 1806 showing ”Edw[ar]d Kelly, a Magician in the Act of invoking the Spirit of a Deceased Person”](https://www.newyorkalmanack.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/An-engraving-from-1806-showing-Edward-Kelly-a-Magician-in-the-Act-of-invoking-the-Spirit-of-a-Deceased-Person-232x300.jpg) Before burial, bodies were kept in the hospital cellar. One midnight a male voice was heard from below as if a corpse had regained consciousness. The space was searched, bodies examined, but no living person identified.

Before burial, bodies were kept in the hospital cellar. One midnight a male voice was heard from below as if a corpse had regained consciousness. The space was searched, bodies examined, but no living person identified.

After making cadavers speak on several occasions during surgical exercises, he was refused a diploma for his irreverent behavior.

Because of the large numbers of war casualties and a dire shortage of medical personnel, the eighteen-year-old was placed in charge of nursing a group of Prussian prisoners who were stricken with typhus.

When Napoleon Bonaparte fell in April 1814, these soldiers requested that their medical assistant who by now spoke German, would oversee their repatriation to Brandenburg. Upon their safe arrival, the Prussian authorities recognized his service by awarding him the Iron Cross.

Being stuck in Berlin and having entertained a German audience of soldiers and medical staff with his abilities as a ventriloquist and impersonator, Vattemare decided to turn his natural gift into a profession.

Berlin & London

In the course of the eighteenth century, the shift from ventriloquism as a manifestation of spiritual forces towards a form of entertainment took place at traveling funfairs. Presenting himself as “Monsieur Alexandre, Ventriloque & Gentilhomme,” Vattemare began his career as a self-styled aristocrat and multi-lingual itinerant actor with a tour of the German-speaking territories and went on to become extremely popular throughout Europe.

Even in the wake of Napoleonic invasions that had stirred strong anti-French feelings, he delighted the public with satirical shows in which he impersonated as many as ten separate characters in a single play. For two decades, Vattemare would hold European audiences in thrall.

Early performances of ventriloquism did not involve the use of a dummy. Instead, performers would have conversations with fake people in another room or in compromising situations (talking to chimney-sweeps up chimneys, or addressing a “Jack-in-the-Box”).

It was not until later that practitioners began using puppets to enhance the illusion of a separate voice, a form of stagecraft that involved mastering the skill to produce sounds without moving the lips.

V

attemare enjoyed his greatest success in England where he settled down with his family for five years. Between 1820 and 1825, he played to packed houses in Scotland and Ireland during the summer and in London during the winter, being hailed as a great actor. He had a run of nearly two hundred performances at the recently renamed Adelphi Theatre in the Strand, Westminster (formerly “Sans Pareil” theater).

attemare enjoyed his greatest success in England where he settled down with his family for five years. Between 1820 and 1825, he played to packed houses in Scotland and Ireland during the summer and in London during the winter, being hailed as a great actor. He had a run of nearly two hundred performances at the recently renamed Adelphi Theatre in the Strand, Westminster (formerly “Sans Pareil” theater).

The show was based on a specially created text in 1822 by W. T. Moncrieff, an author of popular melodramas, entitled The Adventures of a Ventriloquist: or, The Rogueries of Nicholas, with illustrations by the equally popular Robert Cruikshank. In this one-man show, Vattemare transformed into dozens of different characters, male or female, each with their own costumes and voices.

During his time in Britain, he became intrigued by the nation’s passion for collecting. After the disruption of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and the devastation of the French Revolution, London’s auction houses were flooded with antiquities and rarities.

This was also the era of archaeological digging. Royals and politicians visited excavation sites; newspaper headlines announced the latest finds; and thousands flocked to see ancient artifacts in museums all over Europe.

Agents working on behalf of the diplomat Thomas Bruce, Lord Elgin, shipped the (“Elgin”) Marbles from the Parthenon in Athens to the British Museum between 1801 and 1812.

Naturalist and collector William Bullock bought a house in Piccadilly in 1812 that he named “The Egyptian Hall” for the display of over 15,000 curiosities. In 1819, he sold off his collection of objects in an auction lasting twenty-six days which attracted enormous publicity. Vattemare got the collecting bug as well.

Between 1815 and 1820 Monsieur Alexandre had brought his one-man show to Prussia, Denmark, Poland, Russia, the Low Countries, Hungary, Bohemia, Britain and Ireland. He was met with triumph wherever he appeared, applauded by Queen Victoria and the Russian Tsar and adored by Goethe, Alexander Pushkin and Walter Scott.

Between 1815 and 1820 Monsieur Alexandre had brought his one-man show to Prussia, Denmark, Poland, Russia, the Low Countries, Hungary, Bohemia, Britain and Ireland. He was met with triumph wherever he appeared, applauded by Queen Victoria and the Russian Tsar and adored by Goethe, Alexander Pushkin and Walter Scott.

He returned to Paris in 1826, a wealthy man. Having retired from show-business, he acquired an exclusive apartment on Rue de Clichy and a summer residence at the “Royal” town of Marly-le-Roi. His restless intellect could not cope with retirement.

Vattemare was an Enlightenment character who regarded himself a cosmopolitan and a member of a transnational “Republic of Letters.” A cosmopolitan was not a follower of any particular religious or political authority, but an independent mind and a “citizen of the world,” a person who was at home in all European capitals.

At the same time, this aristocrat was a devoted crusader for the democratization of learning and the free availability of resources. He firmly believed that barriers and borders between nations were artificial lines in the sand that would be removed by mutual understanding.

A multi-national exchange of printed materials would create a beneficial flow of ideas and overcome the narrow-mindedness of isolationist politics.

Two American Tours

During his extensive travels, Vattemare took an interest in the specifics of towns and cities where he performed, partly to gather place-related props and materials for his shows. Upon arrival, he would research local traditions in libraries and museums, keeping a record of many miscellaneous, often unclassified, collections.

He paid attention to either gaps or duplication in the holdings and began a process of classification. His inventories reached vast proportions: 30,000 “doubles” in the library of Vienna; 54,000 in Saint Petersburg; and 200,000 in Munich.

Concerned about a lack of public access to library resources, he opted to devote his private fortune and personal energy to the dissemination of knowledge by a system of international exchange.

In 1839 he set up a privately funded agency at 60 Rue de Richelieu. Seeking the backing of the French government, he was frustrated by an indifferent attitude amongst ministers.

On advice of the Marquis de Lafayette, a former volunteer in the Continental Army under General George Washington, he decided to visit the newly formed Republic of the United States in search of support.

On arrival in the city of New York in October 1839 Vattemare intended to present himself as a cultural ambassador, but his reputation as a performer had preceded him and journalistic interest in the curious Monsieur Alexandre was enormous.

He reluctantly agreed to stage one performance at Manhattan’s Park Theatre. The show was soon followed by a public meeting at Clinton Hall on Nassau and Beekman Streets, where he introduced his idea of a system of global cultural exchange.

Leaving Manhattan, Vattemare continued his journey to Washington D.C. Although somewhat discouraged by the lack of public libraries in the country, he was determined to proceed with the project. And he did encounter enthusiasm for his ideas.

President Martin Van Buren backed the proposal that great libraries should donate their duplicates to a “clearing house” and in 1840 Congress passed legislation favoring international exchange. From Maine to Florida pledges were made to supply books, maps and significant objects representing regional cultures.

The city of Philadelphia presented him with a copy of the Constitution, dedicated to the “friend of universal knowledge.” In 1841 in Boston, he participated in discussions about the founding of a public library. Shortly after he returned to France.

In May 1847, Vattemare undertook a second trip to the United States that would last until December 1850. He carried with him fifty cases of French archives, maps, documents, prints and coins weighing 11,500 kilos, for which he laid out $8,000 in insurance.

The project was making progress. In 1848, Congress approved an annual indemnity for him in support of his scheme. In April that same year, an act enabling the formation of a first public library in Boston was passed by the General Court of Massachusetts.

Although similar concepts were being considered in several cities and states, Vattemare’s vision of permanent freely available collections housed in great urban institutions made an impact and took hold.

Boston’s start was less imposing. Its first location was the ground floor of a former schoolhouse on Mason Street that opened in March 1854, housing a collection of some sixteen thousand volumes.

Boston’s start was less imposing. Its first location was the ground floor of a former schoolhouse on Mason Street that opened in March 1854, housing a collection of some sixteen thousand volumes.

In 1887, Charles Follen McKim (of McKim, Mead and White)was appointed to design new premises for the Library and he completed his monumental “palace for the people” at Copley Place eight years later.

Its French connection was maintained. The Library is the only building in America that can boast a mural by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Europe’s outstanding muralist at the time. Vattemare donated a collection of books from France.

His inspirational contribution to the project was highlighted by a commemorative plaque placed in the entrance hall to the building.

Legacy

An admirer of America, Vattemare had an additional project in mind: the creation of an American library in Paris for which he collected books and items of “Americana.” By 1860, the “Fonds Vattemare” contained some 14,000 volumes, mostly official publications of the federal government.

Part of this collection was saved from the fire of 1871 at the old Paris City Hall. It became the nucleus around which the “Bibliothèque administrative de la Ville de Paris” built a unique collection of publications, a lasting treasure trove for researchers in urban, economic and legal history.

Vattemare reached the height of his success in France between 1850 and 1855 when he acted as the French cultural ambassador to the United States and put in charge of the American contribution to the “Exposition Universelle,” held on the Champs-Élysées from May to November 1855.

By 1860, as many as 300,000 volumes had been exchanged between the United States and France, but the political tide was turning. France had become involved in the Crimean War and America was absorbed by the events leading up to the Civil War.

Resources on both sides of the Atlantic dried up and Vattemare was accused of being a fantast. If that was indeed the case, it substantiates the apparent contradiction that the true “man of action” may well be a dreamer. The project faltered after the death of its founder, but the idea behind it survived.

Vattemare inspired the international exchanges of the Smithsonian Institution; in 1877, a French Commission of International Exchanges was founded in Paris; Belgian authorities organized an international Conference on Exchanges in 1880, followed by the signing of the international Berne Convention in 1886 (dealing with the protection of works and the rights of their authors).

Vattemare inspired the international exchanges of the Smithsonian Institution; in 1877, a French Commission of International Exchanges was founded in Paris; Belgian authorities organized an international Conference on Exchanges in 1880, followed by the signing of the international Berne Convention in 1886 (dealing with the protection of works and the rights of their authors).

Above all, his name should be remembered as being a driving force behind the founding of the first modern public libraries in the United States.

His burning ambition was based on the philosophical concept that free and open access to all reading resources is the mark of an advanced society. That is the Enlightenment lesson that Vattemare impressed upon America.

With the inauguration of the New York Public Library and the opening of Boston’s monumental new library building, 1895 was a memorable year for the nation’s cultural and intellectual history.

Read more about libraries in New York State.

Illustrations, from above: The New York Public Library Main Branch during its late stage construction in 1908 with the lion statues not yet installed at the entrance; Samuel Tilden portrait by Jose Maria Mora ca. 1870; An engraving from 1806 showing ”Edw[ar]d Kelly, a Magician in the Act of invoking the Spirit of a Deceased Person”; W.T. Moncrieff’s Memoirs and Anecdotes of Monsieur Alexandre, the Celebrated Dramatic Ventriloquist with illustrations by Robert Cruikshank (London: J. Lowndes, 1822); Printed playbills for Vattemare performances in 1822; Mural “Philosophy” by Puvis de Chavannes at Boston Public Library, 1895-6; and a detail from John Jackson’s Portrait of Vattemare in London, 1826 (Bibliothèque Hôtel de Ville, Paris).

Source link