70,000+ new homes could be built along Interborough Express with zoning changes

View of the Bay Ridge Branch, which would be incorporated in the proposed Interborough Express. Adjacent to the Fort Hamilton Parkway station. Credit: Marc A. Hermann / MTA on Flickr

More than 70,000 new homes could be built within a half-mile of the proposed Interborough Express (IBX) train line through land-use changes. Outlined in an analysis released Thursday by the New York Building Congress, and first reported by the New York Times, implementing land use changes could lead to the development of tens of thousands of new homes within a 10-minute walk of the 19 stops along the 14-mile light rail line, with the potential to exceed 100,000 units over a decade. However, these changes would face many obstacles, as the IBX will run through diverse neighborhoods with varying residential densities and local willingness to welcome new homes.

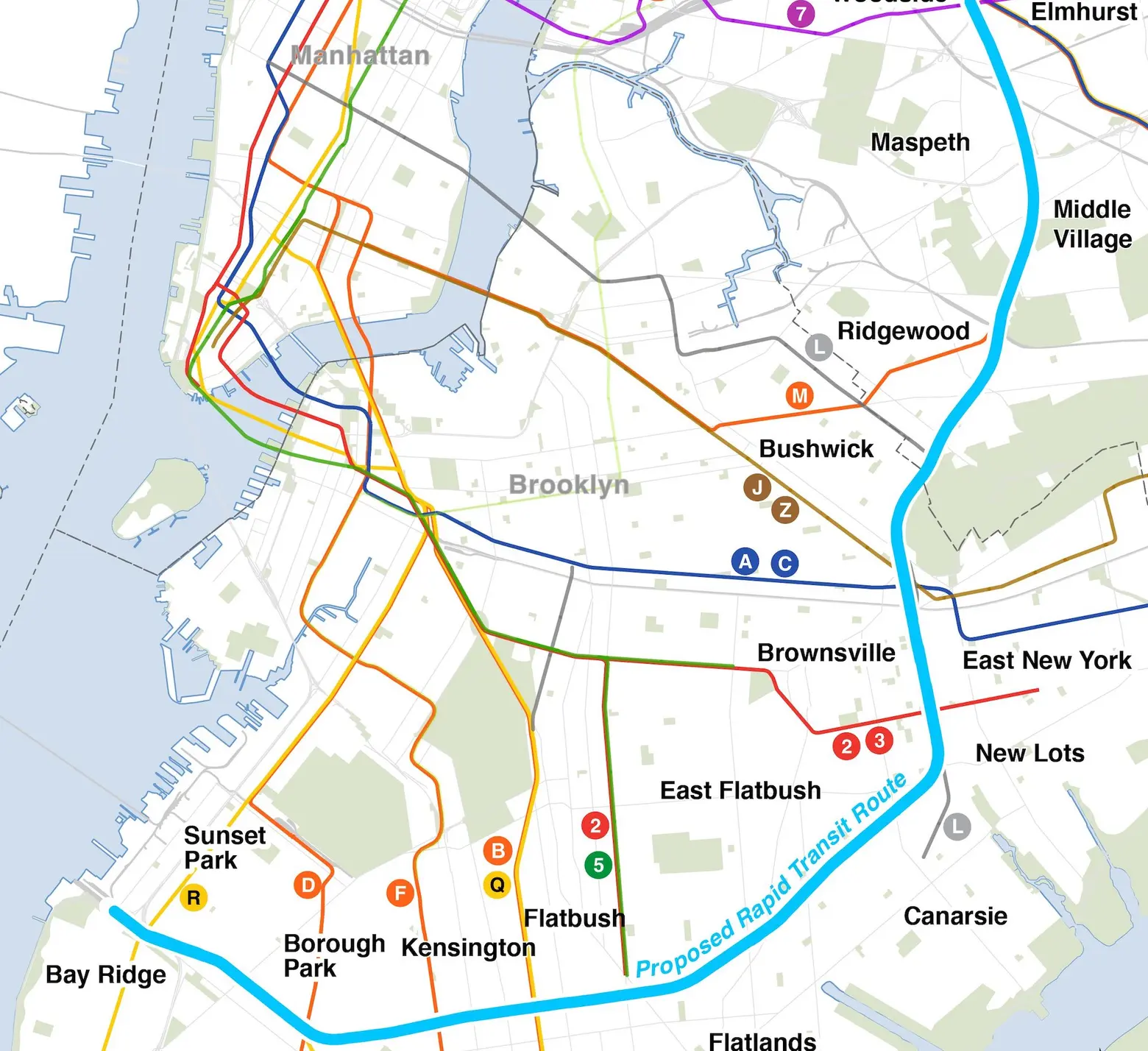

First announced in Gov. Kathy Hochul’s 2022 State of the State address, the Interborough Express (IBX) would transform the existing Bay Ridge Branch freight line into a 14-mile transit link between Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, and Jackson Heights, Queens. The project would connect underserved neighborhoods to 17 subway lines and 51 bus routes, dramatically reducing travel times between the two boroughs.

These neighborhoods include Sunset Park, Borough Park, Kensington, Midwood, Flatbush, Flatlands, New Lots, Brownsville, East New York, Bushwick, Ridgewood, Middle Village, Maspeth, and Elmhurst.

In early 2022, the MTA conducted a feasibility study, which estimated that the completed IBX would serve between 74,000 and 88,000 riders daily. In January 2023, the MTA announced its decision to select light rail for the IBX, Hochul stating that it would “provide the best service for customers at the lowest cost per rider,” according to a press release.

The New York Building Congress, a trade group representing construction and real estate companies, views the project as a rare opportunity to expand transit access while making meaningful progress on the city’s dire housing crisis.

In their analysis, the group found wide variation in population density along the IBX route. Neighborhoods like Jackson Heights in Queens and Sunset Park in Brooklyn rival Manhattan in density, while others are significantly less populated. Overall, population density around IBX stations ranges from 11,800 to 132,800 residents per square mile, with a median of 47,657.

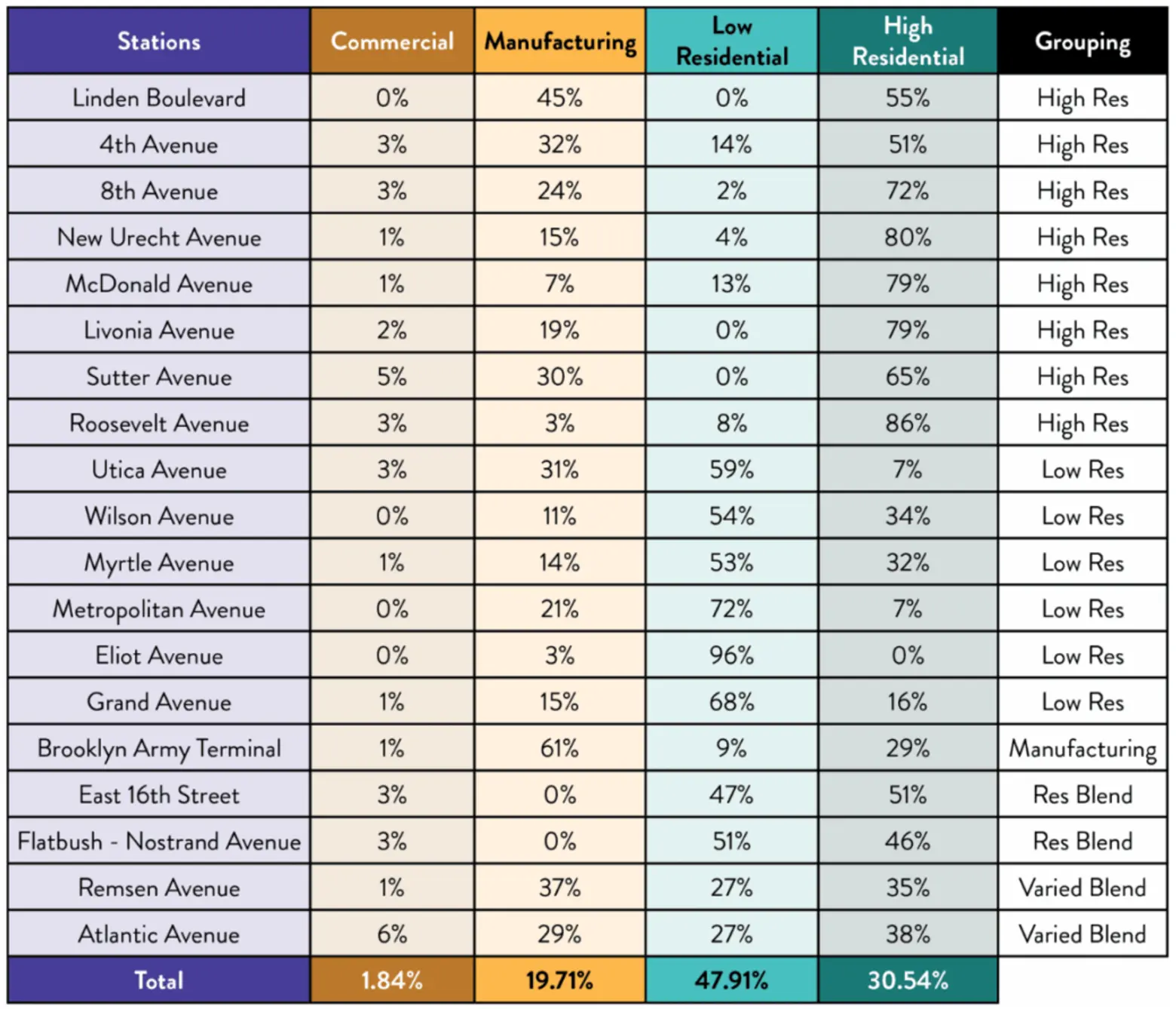

The proposed station areas zoned for high-density residential include 8th Avenue, New Utrecht Avenue, McDonald Avenue, Livonia Avenue, Sutter Avenue, and Roosevelt Avenue, while those with low-density residential zoning include the Eliot Avenue, Grand Avenue, Metropolitan Avenue, and Utica Avenue stations.

Nearly half of the land along the IBX is zoned for low-density residential use, making up 47.91 percent of the corridor. Higher-density residential zones account for 30.54 percent, while manufacturing zones make up 19.71 percent. Just 1.84 percent of the area is zoned for commercial use.

Areas surrounding the Brooklyn Army Terminal and Linden Boulevard stations contain significantly more manufacturing land use—more than double the route’s average—due to their development as industrial corridors in the early to mid-20th century.

Other areas characterized by low-density residential zoning have largely maintained that character over the years, due to their origins as single-family home communities and ongoing resistance from residents and elected officials.

The analysis outlines four scenarios that test different strategies for how zoning changes could be applied: commercial and manufacturing, residential districts, or a hybrid approach.

Scenario one proposes uniform upzoning across all zoning district types, with the potential to create approximately 42,666 new homes. While this approach is mostly neutral and avoids targeting specific areas, it falls significantly short of creating the targeted number of transit-oriented development (TOD) units.

Scenario two would target manufacturing and commercial zones only, minimizing conflict with existing residential communities. It also avoids heavy manufacturing zones that may pose health-related concerns that prevent housing development. This could yield roughly 83,529 homes.

The third scenario focuses exclusively on low-density residential areas—the largest land type along the IBX—promoting a more equitable distribution of new homes across neighborhoods surrounding the proposed stations. It would unlock large areas of land that have seen little new residential development over the last several years.

However, this approach would likely face strong local opposition and require infrastructure upgrades in some neighborhoods. Additionally, limited available space in low-density areas means fewer homes could be built per lot compared to commercial and manufacturing sites.

Council Member Robert Holden, who represents neighborhoods like Middle Village, Maspeth, and other parts of Queens along the IBX, told the New York Times that he doesn’t expect his district to support upzoning.

“We’re opposed to upzoning the district, and anybody that succeeds me would say the same thing,” Holden told the Times. “And if they don’t, they wont get elected.”

The fourth scenario focuses on high-density residential zones, which could generate about 100,200 units—more than any other scenario. Upzoning areas from R6 to R8A would raise FAR caps, allowing more homes in these multi-family neighborhoods. The benefit of this approach is that these areas are already transit-rich and densely populated. It also raises the challenge of avoiding excessive density concentrated around just a few stations.

Scenario five strikes a balanced approach, with moderate upzoning in both low- and high-density residential areas and a more aggressive change to manufacturing and commercial districts. This would allow for roughly 83,059 new homes.

Based on the analysis, the group laid out recommendations to increase housing development along the IBX. First, New York Building Congress recommends the creation of a special IBX Transit-Oriented Development Special District (IBX-TOD SD) along the route. This broader rezoning would resemble the tools included in Mayor Eric Adams’ “City of Yes” housing plan and conform to each neighborhood’s varying housing conditions.

Using scenario five as a model, the IBX-TOD SD could encourage modest upzoning in both low- and high-density residential districts, along with more significant conversions of commercial and manufacturing sites. To protect existing jobs while increasing housing density, the analysis also recommends expanding mixed-use zoning along the route.

“With the right policy tools, the right leadership, and the right timing, the IBX can become a model for integrated transit and housing planning, delivering thousands of new homes, supporting vibrant neighborhoods, and laying the groundwork for a more connected and prosperous New York City,” the analysis reads.

In April, the IBX received a significant boost with the approval of the MTA’s 2025–2029 capital plan, which earmarked $2.75 billion—half of the project’s projected $5.5 billion cost. The project’s fate was up in the air due to a $15 billion gap in the previous capital plan caused by Hochul’s pause on congestion pricing.

Now in its preliminary engineering and design phase, which is expected to take about two years, the IBX is projected to be completed by 2030, according to the Times.

RELATED:

Source link