Fish Mouths: How Anatomy Suggests Ecology

The river roars in the heat of the summer. The water is clear and cool, and a respite from the high sun. An angler leans back, fly-fishing rod in hand, and casts it forward. The fly drops and sinks into the water. Hopefully a fish will bite.

The river roars in the heat of the summer. The water is clear and cool, and a respite from the high sun. An angler leans back, fly-fishing rod in hand, and casts it forward. The fly drops and sinks into the water. Hopefully a fish will bite.

What kind of fish depends on how deep in the water – the surface, mid-depth or bottom – the fly ends up. Fish feed in different parts of the water column, and their bodies and diets are adapted to their feeding strategies. Their mouths alone often give a clue as to where in the water column they feed.

A fish can have three different locations for its mouth: it can be terminal (located at the end of the head), inferior (opening downwards), or superior (opening upwards).

These seemingly simple differences in anatomy can reveal where a fish typically hunts for food. Fish with superior mouths often feed on food above them by targeting prey floating on the surface or by ambushing it from below.

If you watch a herring, such as an alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), you’ll probably see a flash of silver as this fish swims upwards towards its zooplankton prey. Alewives eat all sorts of small invertebrates, snatching them from below with their large, upturned mouths. Their superior mouth looks like an underbite, with their lower jaw jutting out.

Fish with terminal mouths, such as largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), often feed throughout the water column, catching prey wherever they happen to be swimming. Largemouth bass are found around the Northeast, though they are not native.

Stocking efforts have spread them from their native waters in the Mississippi River basin to waters across the country. Like other fish with terminal mouths, such as trout and salmon, the largemouth bass can eat any prey that is swimming right in front of them: zooplankton, crayfish, other fish, and even frogs.

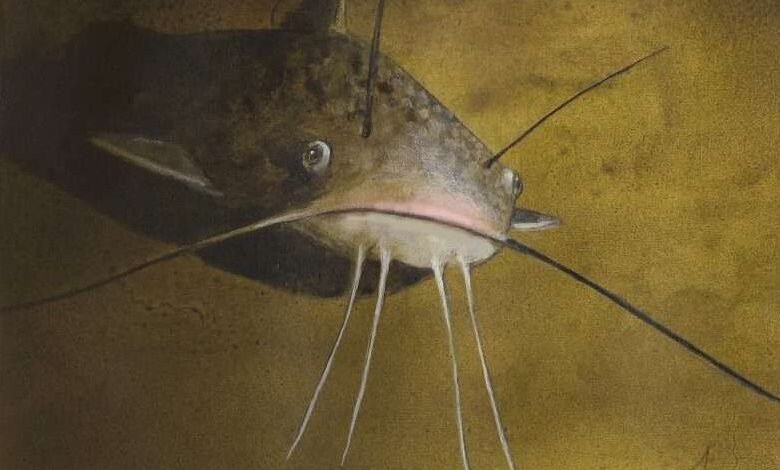

Fish with inferior mouths, located on the underside of their heads, typically feed on river and lake bottoms as they swim along. The longnose sucker (Catostomus catostomus) and brown bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus) are bottom feeders. They eat algae, small invertebrates like copepods (tiny crustaceans), snails, and the aquatic larvae of insects such as mosquitoes.

The bullhead is a catfish, and all catfish have “whiskers” around their mouths, which gives them their name. These whiskers, or barbels, are fleshy cylinders covered in sensory cells. Barbels are often used to find food. (Biologists continue to study what other uses barbels have.) Fish move their barbels around, using touch and taste cells on them to locate prey. This is helpful when the water is too cloudy or dark for the fish to see.

Since catfish feed on the bottom, anglers must ensure their line reaches the bottom. “During the winter, we’ll get people jigging for them,” said Joseph Murzin of Fish Tails Bait and Tackle in Barnstead, New Hampshire. Using a weight attached to the fishing line, anglers can drop a hook down towards the bottom and jerk it up and down to attract the fish.

Once you pull a catfish out of the water, you may notice that its mouth looks very large. This is because catfish have protrusible mouths that jut forward to enlarge the mouth cavity and allow it to suck in prey. Largemouth and smallmouth bass also have this adaptation.

When fish with protrusible mouths are near something tasty, they flare their gills or gill plates and open their jaws quickly. The movement is so fast that it creates a vacuum.

“Almost immediately they close up shop, so the intended prey cannot escape,” explained John Viar of New Hampshire Fish and Game. This is called suction feeding, and the vacuum generated can be quite strong.

The bottom-feeding burbot (Lota lota), another suction feeder found in cool, deep waters, sometimes has “stomach pearls,” as Viar calls them, or small rocks that they can’t avoid sucking in along with prey – one drawback to a great adaptation.

Next time you’re cooling off in a river, fishing, or wandering through an aquarium, look closely at the fish swimming by. Do you see the location of its mouth? Where do you think it feeds?

Jenna O’del is a biologist and science writer based in Rhode Island. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.

Source link