Moses Roper’s Escape from American Slavery

The following excerpt is from A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper, from American Slavery published in 1838. Moses Roper (ca. 1815 – 1891) was an African American abolitionist, author and orator. He gave thousands of lectures in Great Britain and Ireland to inform the European public about the brutality of American slavery.

The following excerpt is from A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper, from American Slavery published in 1838. Moses Roper (ca. 1815 – 1891) was an African American abolitionist, author and orator. He gave thousands of lectures in Great Britain and Ireland to inform the European public about the brutality of American slavery.

Fearing the [schooner] Fox would not sail before I should be seized, I deserted her, and went on board a brig sailing to Providence, that was towed out by a steamboat, and got thirty miles from Savannah [Georgia].

During this time I endeavored to persuade the steward to take me as an assistant, and hoped to have accomplished my purpose; but the captain had observed me attentively, and thought I was a slave, he therefore ordered me, when the steamboat was sent back, to go on board her to Savannah, as the fine for taking a slave from that city to any of the free states is five hundred dollars.

I reluctantly went back to Savannah, among slaveholders and slaves. My mind was in a sad state; and I was under strong temptation to throw myself into the river. I had deserted the schooner Fox, and knew that the captain might put me into prison till the vessel was ready to sail; if this had happened, and my master had come to the jail in search of me, I must have gone back to slavery.

But when I reached the docks at Savannah, the first person I met was the captain of the Fox, looking for another steward in my place. He was a very kind man, belonging to the free states, and inquired if I would go back to his vessel. This usage was very different to what I expected, and I gladly accepted his offer. This captain did not know that I was a slave. In about two days we sailed from Savannah for New York.

I am (August, 1834) unable to express the joy I now felt. I never was at sea before, and, after I had been out about an hour, was taken with sea-sickness, which continued five days. I was scarcely able to stand up, and one of the sailors was obliged to take my place.

The captain was very kind to me all this time; but even after I recovered, I was not sufficiently well to do my duty properly, and could not give satisfaction to the sailors, who swore at me, and asked me why I shipped, as I was not used to the sea.

We had a very quick passage; and in six days, after leaving Savannah, we were in the harbor at Staten Island, where the vessel was quarantined for two days, six miles from New York.

The captain went to the city, but left me aboard with the sailors, who had most of them been brought up in the slave-holding states, and were very cruel.

The captain went to the city, but left me aboard with the sailors, who had most of them been brought up in the slave-holding states, and were very cruel.

One of the sailors was particularly angry with me because he had to perform the duties of my place; and while the captain was in the city, the sailors called me to the fore-hatch, where they said they would treat me.

I went, and while I was talking, they threw a rope round my neck and nearly choked me. The blood streamed from my nose profusely. They also took up ropes with large knots, and knocked me over the head.

They said I was a negro; they despised me; and I expected they would have thrown me into the water. When we arrived at the city these men, who had so ill treated me, ran away that they might escape the punishment which would otherwise have been inflicted on them.

When I arrived in the city of New York, I thought I was free; but learned I was not, and could be taken there. I went out into the country several miles, and tried to get employment, but failed, as I had no recommendation.

I then returned to New York; but finding the same difficulty there to get work, as in the country, I went back to the vessel, which was to sail eighty miles up the Hudson River, to Poughkeepsie.

When I arrived, I obtained employment at an inn, and after I had been there about two days, was seized with the cholera, which was at that place. The complaint was, without doubt, brought on by my having subsisted on fruit only, for several days, while I was in the slave states.

The landlord of the inn came to me when I was in bed, suffering violently from cholera, and told me he knew I had that complaint, and as it had never been in his house, I could not stop there any longer.

No one would enter my room, except a young lady, who appeared very pious and amiable, and had visited persons with the cholera. She immediately procured me some medicine at her own expense and administered it herself; and, whilst I was groaning with agony, the landlord came up and ordered me out of the house directly.

Most of the persons in Poughkeepsie had retired for the night, and I lay under a shed on some cotton bales. The medicine relieved me, having been given so promptly, and next morning I went from the shed and laid on the banks of the river below the city.

Towards evening, I felt much better, and went on in a steamboat to the city of Albany, about eighty miles. When I reached there, I went into the country, and tried for three or four days to procure employment, but failed.

At that time, I had scarcely any money, and lived upon fruit, so I returned to Albany, where I could get no work, as I could not show the recommendations I possessed, which were only from slave states, and I did not wish any one to know I came from them.

After a time, I went up the western canal as steward in one of the boats. When I had gone about 350 miles up the canal [the Erie Canal, as far as Rochester], I found I was going too much towards the slave states, in consequence of which, I returned to Albany, and went up the northern canal [Champlain Canal], into one of the New England states – Vermont.

The distance I had traveled, including the 350 miles I had to return from the west, and the 100 to Vermont, was 2,300 miles. When I reached Vermont, I found the people very hospitable and kind; they seemed opposed to slavery, so I told them, I was a run-away slave.

I hired myself to a firm in Sudbury. After I had been in Sudbury some time, the neighboring farmers told me that I had hired myself for much less money than I ought. I mentioned it to my employers, who were very angry about it; I was advised to leave by some of the people round, who thought the gentlemen I was with would write to my former master, informing him where I was, and obtain the reward fixed upon me.

Fearing I should be taken, I immediately left and went into the town of Ludlow, where I met with a kind friend, Mr. _______* who sent me to school for several weeks. At this time, I was advertised in the papers [as an escaped slave] and was obliged to leave; I went a little way out of Ludlow to a retired place, and lived two weeks with a Mr. ________ deacon of a church at Ludlow; at this place, I could have obtained education, had it been safe to have remained.

* It would not be proper to mention any names, as a person in any of the States in America, found harbouring a slave, would have to pay a heavy fine.

From there I went to New Hampshire, where I was not safe, so went to Boston, Massachusetts, with the hope of returning to Ludlow, a place to which I was much attached.

At Boston, I met with a friend, who kept a shop, and took me to assist him for several weeks. Here I did not consider myself safe, as persons from all parts of the country were continually coming to the shop, and I feared some might come who knew me.

I now had my head shaved, and bought a wig, and engaged myself to a Mr. Perkins, of Brookline, three miles from Boston, where I remained about a month. Some of the family discovered that I wore a wig, and said that I was a runaway slave; but the neighbors all around thought I was a white, to prove which I have a document in my possession to call me to military duty.

The law is. that no slave or colored person performs this, but every other person in America, of the age of twenty-one, is called upon to perform military duty once or twice in the year, or pay a fine.

COPY OF THE DOCUMENT.

“Mr. Moses Roper, You being duly enrolled as a soldier in the company, under the command of Captain Benjamin Bradley, are hereby notified and ordered to appear at the Town House in Brookline, on Friday, 28th instant, at 3 o’clock P.M., for the purpose of filling the vacancy in said Company, occasioned by the promotion of Lieut. Nathaniel M. Weeks, and of filling any other vacancy which may then and there occur in said Company, and there wait further orders. By order of the Captain, E. P. WENTWORTH, Clerk.” Brookline, Aug. 14th, 1835.”

I then returned to the city of Boston, to the shop were I was before. Several weeks after I had returned to my situation two colored men informed me that a gentleman had been inquiring for a person whom, from the description, I knew to be myself, and offered them a considerable sum if they would disclose my place of abode; but they being much opposed to slavery, came and told me, upon which information I secreted myself till I could get off.

I went into the Green Mountains for several weeks, from thence to the city of New York, and remained in secret several days, till I heard of a ship, the Napoleon, sailing to England, and on the 11th of November, 1835, I sailed, taking with me letters of recommendation to the Rev. Drs. Morison and Raffles, and the Rev. Alex. Fletcher.

The time I first started from slavery was in July, 1834, so that I was nearly sixteen months in making my escape.

On the 29th of November, 1835, I reached Liverpool, and my feelings when I first touched the shores of Britain were indescribable, and can only be properly understood by those who have escaped from the cruel bondage of slavery.

When I reached Liverpool, I proceeded to Dr. Raffles, and handed my letters of recommendation to him. He received me very kindly, and introduced me to a member of his church, with whom I stayed the night. Here I met with the greatest attention and kindness.

The next day, I went on to Manchester, where I met with many kind friends, among others Mr. Adshead, a hosier of that town, to whom I desire, through this medium, to return my most sincere thanks for the many great services which he rendered me, adding both to my spiritual and temporal comfort.

I would not, however, forget to remember here, Mr. Leese, Mr. Childs, Mr. Crewdson, and Mr. Clare, the latter of whom gave me a letter to Mr. Scoble, the Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society. I remained here several days, and then proceeded to London, December 12th, 1835, and immediately called on Mr. Scoble, to whom I delivered my letter; this gentleman procured me a lodging.

I then lost no time in delivering my letters to Dr. Morison and the Rev. Alexander Fletcher, who received me with the greatest kindness, and shortly after this Dr. Morison sent my letter from New York, with another from himself, to the Patriot newspaper, in which he kindly implored the sympathy of the public in my behalf.

The appeal was read by Mr. Christopherson, a member of Dr. Morison’s church, of which gentleman I express but little of my feelings and gratitude, when I say that throughout he has been towards me a parent, and for whose tenderness and sympathy I desire ever to feel that attachment which I do not know how to express.

I stayed at his house several weeks, being treated as one of the family. The appeal in the Patriot, referred to getting a suitable academy for me, which the Rev. Dr. Cox recommended at Hackney, where I remained half a year, going through the rudiments of an English education.

Hudson River Maritime Museum Contributing Scholar George A. Thompson found, cataloged and transcribed these excerpts. John Warren provided annotations.

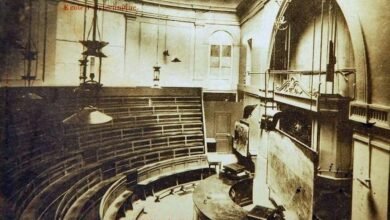

Illustrations, from above: Moses Roper, 1840; and Roper’s illustration of a device used to torture him for running away from slavery, 1838.

Source link