Goldenrod Crab Spiders: Masters of Disguise

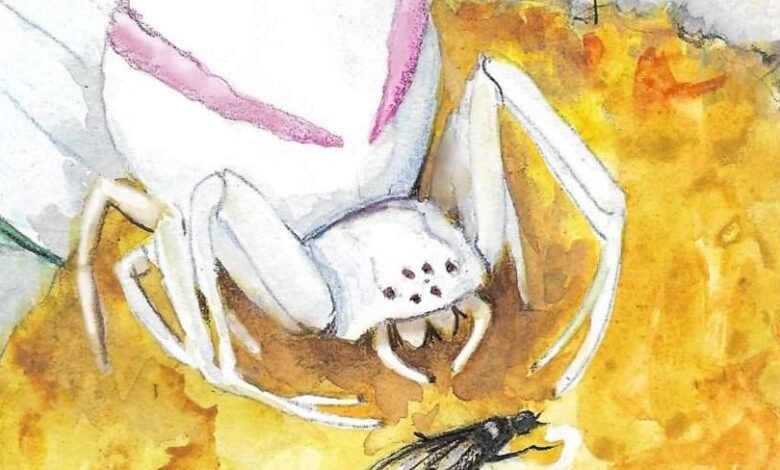

On a spring morning walk, I stop to smell a painted trillium and am greeted by a goldenrod crab spider (Misumena vatia). Bending down for a sniff of the white and pink blooms, I am face to face with the perfectly camouflaged white spider, hidden thanks to a remarkable color changing ability.

On a spring morning walk, I stop to smell a painted trillium and am greeted by a goldenrod crab spider (Misumena vatia). Bending down for a sniff of the white and pink blooms, I am face to face with the perfectly camouflaged white spider, hidden thanks to a remarkable color changing ability.

A member of the family Thomisidae, goldenrod crab spiders are both crabby and spider-y. A medium-sized crab spider, these creatures are familiar garden visitors across southern Canada and the United States.

They are typically white or yellow with two pink or red bands along the sides of the abdomen. A sexually dimorphic species, females can weigh 100 times what a male weighs.

One of the key identifying features for the species is the arrangement of the spider’s forelegs, known as raptorial limbs. The two front legs are positioned skywards rather than forwards, twisting them into a laterigrade, or crablike, posture, not dissimilar to the smartphone shrug emoji. When startled, they crabwalk.

Unlike most spiders that spin webs to catch their prey, this sit-and-wait predator saves its energy by hiding in plain sight. Taking advantage of attractive flowers, the goldenrod crab spider camouflages on brightly colored petals, waiting to pounce on unsuspecting pollinators such as flies and bumblebees.

External digestion allows them to capture and consume insects that are unusually large compared to their body size. First, the spider grasps prey with its legs and

immobilizes it with venom. Then, the spider injects the prey with powerful enzymes, liquifies their insides and slurps out the tissues.

Goldenrod crab spiders are also a bit chameleon-y. They are unique in their ability to change color to match the flower they are sitting on: if they’re hunting on a daisy, they’ll turn white, but if they’re hunting on a sunflower, they’ll turn yellow.

This color change process from white to yellow and back again can take several days. (Admittedly unlike chameleons, who can change almost instantaneously.) Arrangement of their eyes allows them to see the plants and their own bodies simultaneously, so, to match their outfit to the flower, they likely eyeball it.

The crab spider’s ability to change its appearance is a result of the concentration of its body pigments. The spider is covered by a transparent cuticle. Below, underneath the exoskeleton, is the hypodermis, aka the color factory.

Inside, pigments called ommochromes produce bright yellow, and refraction of guanine crystals produces white. When light lands on a spider, the color

reflected is a combination of the pigment contents.

Basically, if the spider wants to appear more yellow, it builds more ommochrome granules. If it wants to appear white, it breaks those granules back down again.

Though the phenomenon has been studied since 1891, the purpose behind the color change is still an area of active research. For centuries, the basic explanation was camouflage: blend into a flower and receive free meal delivery. But recent studies show that there might be more going on than previously thought.

Because many insects see differently than humans via ultraviolet (UV) light, the crab spider may still be visible to a number of other insects. While the UV-absorbing

spider might blend in on a UV-absorbing white flower, the spider might stand out on a UV-reflecting yellow flower.

But this depends on the insect. One study found that honey bees may use green signal receptors unless they are very close to flowers, meaning the spiders stay well-

hidden despite a UV color contrast, while another study found that honey bees can detect the contrast in colors, and may actually be indifferent to it. More research is needed on the topic.

So why bother changing color at all? Maybe the reason is both defensive (to hide from predators like birds) and aggressive (to lure prey). In some cases, the UV contrast might actually attract an insect, like a glowing nectar guide. Or it might help protect them from solar radiation. Either way, scientists say the skill is unlikely to be solely due to chance.

Goldenrod crab spiders appear on a variety of flowers that bloom over much of the spring, summer, and fall. By the time the spiders have mated, and young spiderlings have hatched, late blooming goldenrod species provide a reliable hunting ground and a good opportunity for observation.

These color-changing phenoms are common in woodlots and meadows but are often missed, so keep your eye out while you stop to admire the flowers.

Read more about spiders in New York State.

Lee Toomey is an ecologist currently living in Burlington, Vermont. They enjoy looking around for things outside. Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation: nhcf.org.

Source link