Black History, Birthright Citizenship & Civil Rights

Very few protections existed under state laws for free Black people during the era of enslavement and their actions were strictly regulated.

Very few protections existed under state laws for free Black people during the era of enslavement and their actions were strictly regulated.

In New York free Black citizens faced legal limitations on voting rights, property ownership, and social interactions, some for nearly a century after the abolition of slavery.

In the early 18th century New York’s Black Codes banned meetings, owning weapons, being on the street after dark, testifying in court, and more. Free Black people were forbidden from engaging in trade with enslaved people; restricted in their ability to conduct business and buy or lease land; subjected to laws that criminalized unemployed men, or those working jobs whites did not recognize as legitimate.

While New York initially had property requirements for voting for both Black and white men, the 1821 constitution eliminated these requirements for white men but kept them for Black men, effectively disenfranchising most Black men who had been able to vote. The property requirement for Black men was set at a prohibitive $250 (equivalent to $6,000 in 2024).

In 1831, Black people were excluded from serving on juries and were not allowed admittance to state poorhouses, insane asylums, and other institutions.

In 1846 a New York State referendum ending the property restriction and allowing equal voting rights for black men was widely defeated — 71% to 29%. Northern New York however, widely supported equal rights.

The referendum passed in Clinton County, where 73% of voters voted to end the discrimination; in Essex County 71% supported the change; and Washington, Franklin, and Warren counties were among only 10 counties to vote “yes”.

African-American men did not obtain equal voting rights in New York until ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, in 1870. Black women would have to wait another 50 years.

Barring Free Black People

Between 1822 and 1854, courts in 12 states, including Pennsylvania and California, ruled that free Black people were not citizens.

For example, in 1805, Maryland enacted a law requiring all free Black people to petition the court for a “Certificate of Freedom” as a condition of residency.

In 1806, Virginia passed a law mandating that all free Black people leave the state within one year or face re-enslavement.

In 1811, Delaware passed a law providing that any free Black person who left the state for six months or more forfeited state residency.

In 1822, South Carolina passed a law prohibiting free Black people from moving to or from the state.

In 1830, North Carolina passed a law providing that enslaved people could only be granted freedom on the condition that they left the state within 90 days and “never returned.”

In 1833, the Alabama legislature banned all free Black people from entering the state, and under Alabama law the color of a Black person’s skin gave rise to a presumption that he or she was enslaved. The following year, the Alabama legislature expanded on this law, making it illegal to emancipate an enslaved Black person within Alabama’s borders.

In 1835, the Missouri General Assembly passed a law that required free Black people who were not citizens of the United States to apply for a license to remain in the state. Those who failed to do so faced fines up to $100, incarceration, and expulsion from Missouri.

Although it was among the first laws limiting immigration in the United States, legal decisions effectively applied the law to most Black people, and imposed onerous requirements.

Free Black residents had to establish continuous residency for at least a decade and “produce satisfactory evidence… that [the applicant] is of good character and behavior, and capable of supporting [themselves] by lawful employment.”

The law also obligated Black people to obtain a new license each time they moved to a different county.

In 1837, the Missouri Supreme Court upheld the license law in the case of a free Black man arrested and jailed by the mayor of St. Louis. In challenging his confinement, the man had argued that the U.S. Constitution entitled him to the protections of birthright citizenship and that the license law violated his constitutional rights.

Part of this essay was drawn from the Equal Justice Initiative Calendar.

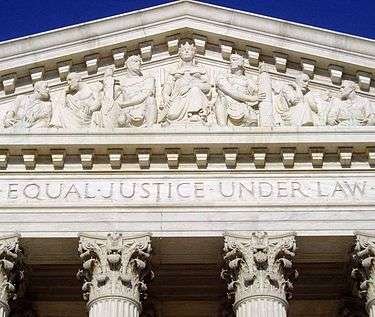

Illustration: “Equal Justice Under the Law” inscription on the front of the Supreme Court Building, ca. 1934.

Source link