Victor Lustig: Conman and Counterfeiter

In 1889 the Third Republic celebrated the centennial of the French Revolution with the opening of a grand international exhibition and the inauguration of the Eiffel Tower.

In 1889 the Third Republic celebrated the centennial of the French Revolution with the opening of a grand international exhibition and the inauguration of the Eiffel Tower.

Politically, France remained divided into three political camps. On the left of the political spectrum, Republicans embraced the democratic reforms initiated by the French Revolution. On the right, Monarchists aimed at reinstating the link between Royalty and (Catholic) Church, whilst Bonapartists demanded the imposition of law and order at home and the maintenance of a powerful presence abroad.

Shovel & Trowel

Political conflict over time has affected the face of Paris. During the nineteenth century, Bonapartists transformed the city’s physical structure with the aim of establishing a grand capital that would stand as a testament to the nation’s cultural dominance.

They sought to assert political ambitions by leaving their mark on Paris with shovel and trowel. Architecture was a political statement. Once the Republicans entered the fray, they set out to impose modernist ideas on urban planning.

In January 1886, Édouard Lockroy was elected Minister of Commerce & Industry. His background was intriguing. Having fought as a volunteer in the Third Italian War of Independence, he had participated in anti-Bonapartist battles and his political partisanship earned him several stints in prison. He was first elected to the National Legislature in 1873 as a radical Republican representing Paris.

One of his briefs as Minister was to make arrangements for the 1889 “Exposition Universelle,” including plans for new buildings at the exhibition site along the Champs de Mars. Lockroy used his position to make sure that the Republicans would leave a memorable mark in the capital.

Gustave Eiffel was recognized as a master designer of structures in iron or steel. He had built railroad bridges and train terminals around the world. Parisians had seen his work first hand in the form of the framework for the Statue of Liberty which, in 1885, was assembled outside his workshop before being shipped to New York City. Eiffel was praised as the “Magician of Iron.”

Yet when he was commissioned to execute the construction plan of a wrought iron tower, feelings of outrage were widely expressed. Objectors treated the project as an industrialist “Tower of Babel,” alien to French culture.

The controversy motivated some prominent artists (amongst them Charles Gounod, Alexandre Dumas and Guy de Maupassant) to publish a protest in Le Temps of February 14, 1889, arguing that the “useless and monstrous” edifice would desecrate the city’s dignity.

In spite of the furor, work continued. After completion, “Eiffelomania” swept France and Europe.

In spite of the furor, work continued. After completion, “Eiffelomania” swept France and Europe.

Georges Seurat in 1889 and Henri “Le Douanier” Rousseau in 1890 were the first to paint the Tower. It was “adopted” by artists after Robert Delaunay created his iconic “red” image of her in 1909 (“La Tour rouge” – the first of thirty canvases depicting the Tower).

For the younger generation, the iconic “Iron Lady” was there to stay as an emblem of technology and modernity. Opponents stuck to their demand that the “eyesore” be demolished. After all, on completion the Eiffel Towere was expected to stand for twenty years only, before dismantlement would take place.

Swindling & Scamming

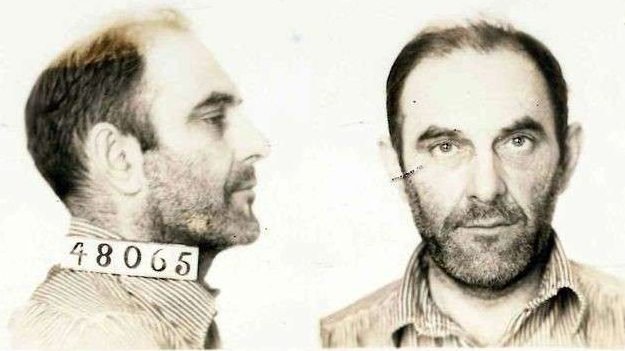

Victor Lustig was born January 4, 1890, into an affluent Bohemian family (then in Austria-Hungary). A clever student and fluent in several languages, he was a rebellious young man without social ambition and reluctant to enter a professional or academic career. Instead he used his charm and intelligence for a much more lucrative activity: swindling.

He left Bohemia in 1909 and settled in Paris where he got hooked on gambling. During this time he sustained a distinctive facial scar in an altercation with a jealous husband whose wife could not resist the young man’s charms. The mark would become consequential in his life story.

Living in Paris, he observed the growing number of American visitors and the craze for luxurious transatlantic travel. To a talented multi-lingual conman, ocean liners seemed to offer a potential of riches. He soon embarked on grand ships sailing between the French Atlantic ports and New York City. Once on board, he started deceiving wealthy old ladies and naïve passengers.

A smart dresser and smooth talker with impeccable manners, he was welcomed at the table of the richest passengers on the voyage. His schemes included one in which he posed as a promising musical producer who sought investment in a lavish but non-existent Broadway production.

In the process, Lustig gained a hunter’s eye for the vulnerability of potential preys. At the same time he honed his skills as a counterfeiter and developed his most successful scam at sea, known as the “Romanian Money Box.” Picking out businessmen amongst the travelers, he would engage with his carefully selected marks and share – in utmost confidence – the “secret” of a money box which he carried with him.

Eventually, he would agree to a private demonstration of the device that was fitted with a printing machine. By inserting a hundred-dollar bill, and after a while of “chemical processing,” he extracted two seemingly authentic copies of the bill which he exchanged on board ship without a trace of suspicion.

After intense persuasion, he would agree to sell the box if the price on offer was right (at least $10,000 and sometimes two and three times that amount).

New York City Interlude

When transatlantic sailings were suspended in the wake of the First World War, Victor opted to settle in New York City. Assuming dozens of aliases and introducing himself as “Count” Victor Lustig (a European title works wonders when facing American clients), he became a master of disguise as he engaged in various counterfeiting schemes. The Romanian Box remained a favorite trick in his repertoire of cons.

In 1922, he fooled a group of investors to pool their money for the “unique” opportunity of purchasing the box. Amongst them was a Texan sheriff who, once he realized he had been scammed, pursued Lustig to Chicago where he confronted him. Once again the victim was tricked by his smooth talking opponent who explained to him that he had handled the precious device incorrectly.

In an act of generosity, Victor repaid his victim a sum of cash in compensation. As it later turned out, the money was counterfeit. The lawman was eventually arrested and accused of passing fake bills in New Orleans. Although imprisoned, he supplied the police with an accurate description of the swindler’s face and scar.

Maybe police officers and Secret Service agents were getting too close for comfort, or maybe Victor was just longing for a change of environment in which to operate, but by 1925 he boarded a liner to France and crossed the Atlantic once again.

Selling the Tower

Selling the Tower

The builders of the Eiffel Tower used “puddle iron,” a form of purified cast iron that enhances resistance to corrosion. The civil engineer himself had warned from the outset that the spread of rust was the biggest challenge to its longevity. He suggested that the Tower needed a new coat of paint at seven year intervals in an operation that would demand sixty tonnes of paint and take some sixteenth months to complete.

When Victor Lustig arrived in Paris, he was struck by an alarmist newspaper article on the future of the rusting Eiffel Tower as the exorbitant cost of maintenance became an issue of serious concern.

To the French government, it was a financial burden. Parisians themselves were and remained divided in their opinion of a structure that was already a decade past its projected lifespan. Many felt that the “unsightly” erection should be taken down.

Divided opinion creates weakness and Lustig was quick to exploit such fragility. He devised a spectacular plan that would make him a legend amongst con artists. He first studied the nature of iron structures and their exposure to rust.

Having acquainted himself with the names of the city’s major metal scrap dealers, he set himself up as Deputy Director of the “Ministère de Postes et Telegraphes.” Using false City of Paris stationary, he requested a meeting with a number of dealers in which he discretely suggested the possibility of a lucrative contract.

After installing himself at the iconic Hôtel de Crillon on the Place de la Concorde (opened in 1909, but the building dates from 1758), he invited the scrap men to enter into a setting of antique furniture, fine marbles and priceless chandeliers.

There he informed them about a “secret” government decision to demolish the Eiffel Tower as the annual expense of its preservation was no longer sustainable. He was personally assigned to invite bids for the right to demolish the Tower and take possession of 15,000 beams and 2.5 million rivets – in weight: 7,000 tons of metal.

Victor transported his clients in rented limousines to the Tower and showed them its rusty state of decline. He repeated the argument that this “hideous” modern structure was not worthy a place amongst venerable monuments such as the Arc the Triomphe or the great Gothic cathedrals.

Vulgarity had reached a new level that year when car maker Citroën was allowed to advertise its name in massive letters on the Tower to defray its maintenance costs (the sign remained in place until 1934). Its destruction would be a public service.

Vulgarity had reached a new level that year when car maker Citroën was allowed to advertise its name in massive letters on the Tower to defray its maintenance costs (the sign remained in place until 1934). Its destruction would be a public service.

Victor made it crystal clear that any transaction had to remain confidential to avoid public interference. His calm demeanor and polished presentation were entirely convincing to André Poisson, one of the invited guests who showed an interest in the project. A young provincial entrepreneur, he was fairly new to Paris and seemed somewhat uncomfortable in the presence of experienced urban rivals. The hunter had identified his prey.

When Victor invited Poisson for a private meeting at the Crillon, the businessman was flattered and fell for the bait. Lustig persuaded him to finalize the contract and accept an added provision. The latter requested a bribe in exchange for his effort of guaranteeing the arrangement to his preferred bidder.

Poisson would pay the “Deputy Director” an amount of $20,000 in cash and an additional $50,000 after the contract was signed. Having received the full sum of money, Lustig left for Austria.

The story never broke. Too embarrassed, Poisson did not file a report with the police. Victor returned that same year in an attempt to repeat the scam. This time, however, one of his “targets” became suspicious and informed the police, prompting him to make a quick return to New York City.

Conning Al Capone

In the 1930s, Lustig took the audacious step to travel to Chicago and request a meeting with the mobster Al Capone. He outlined a business proposition, asking for a $50,000 investment in the scheme with the promise to repay double the amount within a period of just two months. Capone was suspicious, but agreed.

Lustig stored the cash in a safe before returning the full amount to the lender, explaining that the deal had fallen through. Impressed by Victor’s honesty, Al Capone rewarded him with $5,000 to help him “get back on his feet.” The scam’s simplicity demonstrated his mastery of manipulation. The Count’s reputation grew.

In 1930, Lustig went into partnership with a Nebraska chemist named Tom Shaw, initiating a sophisticated counterfeiting operation with an elaborate distribution system to push out large amounts of cash. As the number of phony bills in circulation increased, Victor’s name became associated with the operation.

The situation got worse for Victor when his long-term mistress Billie Mae Scheible, a “Madame” who ran a prostitution racket in New York City, suspected Victor of having an affair with another woman and informed the police of his whereabouts in Manhattan.

The Secret Service started chasing the “Count” in a pursuit that resembles a fictional tale by Arthur Conan Doyle. The hunt was led by agent Peter A. Rubano, an ambitious Italian-American who was born and raised in the Bronx and had made the headlines by trapping the gangster Ignazio “The Wolf” Lupo. It was a cat-and-mouse game that lasted many months, but eventually ended on Broadway.

On a Sunday night in May 1935, elegantly dressed in a Chesterfield coat and – as always – well disguised, Victor Lustig strolled down “The Great White Way” when a plain clothes officer spotted his scar.

On a Sunday night in May 1935, elegantly dressed in a Chesterfield coat and – as always – well disguised, Victor Lustig strolled down “The Great White Way” when a plain clothes officer spotted his scar.

After many near misses of arrest in the past, Rubano and other agents swooped in and confiscated a key from him that gave access to a locker at Times Square subway station. From there, they retrieved $51,000 in counterfeit bills as well as their printing plates.

Awaiting trial, Lustig was held at the “escape proof” Federal Detention Headquarters in Lower Manhattan. Shortly before legal proceedings were set in motion, he fashioned several bed sheets into a rope and climbed out. Pretending to be a window cleaner, he casually shimmied down the building and disappeared in the crowd.

He was recaptured twenty-seven days later in Pittsburgh and sentenced to twenty years in prison on Alcatraz Island. Having contracted pneumonia, he died in March 1947. His passing went virtually unnoticed, as if the conman had played his last disappearing act. On his death certificate his occupation was listed as apprentice salesman and counterfeiter.

Illustrations, from above: Mugshots of Victor Lustig; Robert Delaunay “La Tour rouge,” 1909 (Guggenheim Museum, New York); Charles Gilbert-Martin’s “Gustave Eiffel and Tower,” engraved by Forest Fleury; the Eiffel Tower in 1925 with the illuminated Citroen publicity sign; and Lustig (middle) being questioned by the police in 1935.

Source link